VSF, Los Angeles // June 21, 2025 – July 29, 2025

Serendipity conjures joy. Zemblanity—its quiet silhouette, that fate of discontented accidents—lurks in contrast. Wendy Park’s new solo exhibition, Of Our Own, at Various Small Fires arrives amid both. Against the backdrop of heightened ICE activity in Southern California, Park opens a window onto what’s frequently overlooked: the ordinary yet deeply resonant episodes of city life. In these 30-plus paintings, she offers counter-narratives—intimate tributes to immigrant labor, family, everyday commerce, and flourishing coexistence that hum beneath LA’s Hollywood abstraction.

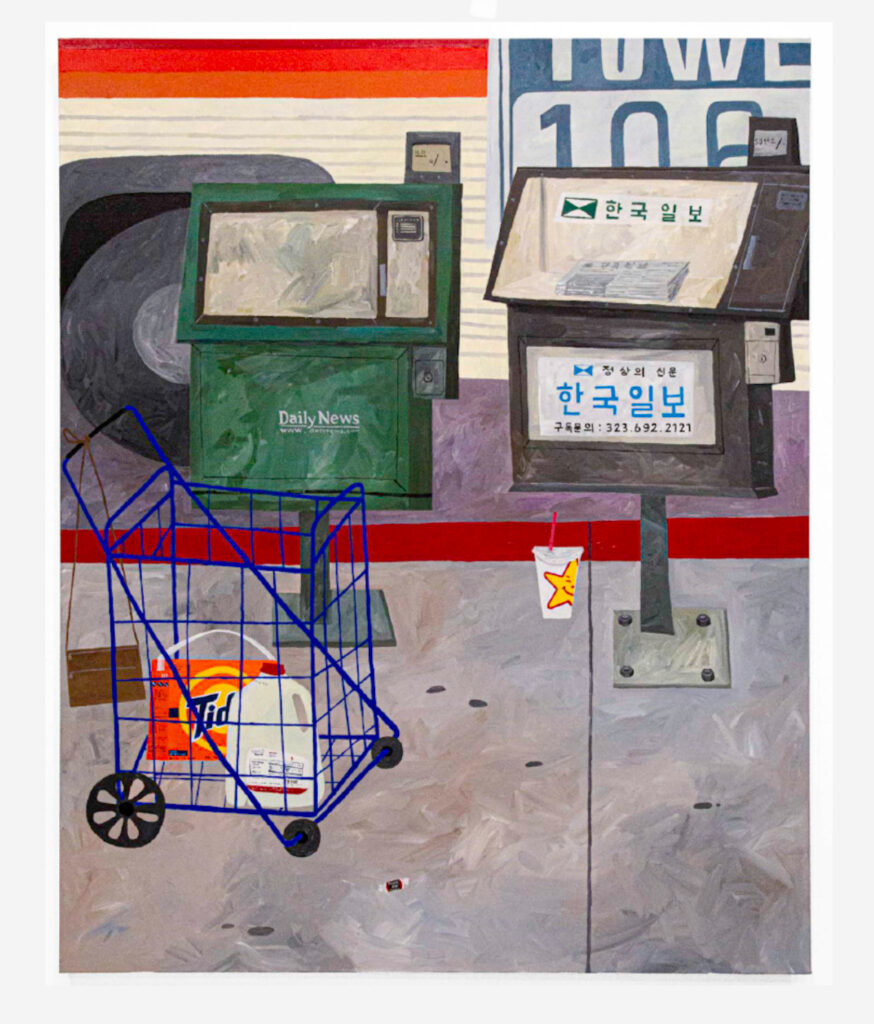

Landscapes of Los Angeles in dominant narratives are glossy—sun-bleached hills, iconic palisades, cinematic boulevards. But Los Angeles doesn’t begin and end at the Hollywood sign. Park’s canvas interrogates the ambience of strip malls, DIY markets, storefronts painted in Korean and Spanish, city blocks alive with the rhythms of working families. She names zones other narratives render invisible.

Each painting is a moment of cartography, mapping not only geography but human intention. Her art pivots not on spectacle but care: the careful brushstroke of scaffolding on a market’s facade, the gleam of a car left careful in a parking-lot courtyard, the warm cast of streetlights promising home at dusk. Park’s vision recasts the mundane as sacred—an immigrant family hanging lanterns for a market opening, a deli clerk pausing mid-slice as a customer arrives, a tow-truck driver leaning on his rig in early morning glow.

Park herself writes: “Produced during a period of heightened ICE activity in Southern California… sharpened my meditations on visibility, vulnerability, and the misrepresentation of immigrant communities in American public discourse.” That sentence transfers to paint. In the softly lit parking-lot scene After Hours, she captures a lone SUV backed into a stall outside a Korean grocery, flickering neon signs reflected in asphalt. It’s still, yet loaded. The viewer senses eyes pressed to windows; hands half-unpacking boxes inside. A quiet watchfulness.

In Saturday Market at Dawn, rows of produce crates—papayas, truckton piles of oranges, radishes bundled in newspaper—are arranged with devotion. No one is present, but their absence speaks: the laborers unloading, the customers arriving, the daily ritual that makes this small world spin. This painting is more than still life—it’s a memorial to tenacity, a record of a harvest of hope. Here Park memorializes labor made invisible, making it visible simply by painting it.

Immigrant experience in America is often reduced to flashy heroic peak or broken cliché. Here Park shows the flicker between—long afternoons of labor, years of saving, the forgettable yet profound accumulation of days. Of Our Own becomes a slow meditation on civility, context, quiet dignity.

LA is a visual language. Park asks us to read its signage as we would script. In Corner Store (한식 반찬), Korean characters glow in a window display, a mix of cold case delights: kimchi, japchae, tteok. The sign is lit in pink neon. Park captures the aluminum door frame, the bent flyer stuck beneath the door, the mismatched vinyl floor tiles inside. It’s as if she’s handed us a phrase in Hangul and asked us to translate it through pigments: what it means to belong, to nourish community, to carve out daily life in a foreign place.

A dozen paintings in the show present bilingual signage—Korean-English, Spanish-English, sometimes tri-lingual. These are not tourist facades but lived environments. The interlanguage becomes a rhythm, a chord. Park paints the cast backdrops of sign letters onto street curbs; she observes how the angles of overhead alfalfa hang like slow punctuation. Language as light. Language as mood. Language as architecture.

Driving across LA is a kinetic experience: ten lanes of highway stretching across valleys, choke points of urban sprawl, the abrupt shift from tony Westside to strip mall after strip mall in South LA. Park’s paintings take the cinematic.

In Eastside Dusk, a vantage from the rear window of a car, she paints windshield wipers refracted through light coming off freeway reflectors. The city’s facade—the chain of billboards, stadium floodlights, a single streetlamp caught mid-burn—motions slows across the windshield’s curvature. It feels fleeting and fixed simultaneously. You sense the drumbeat of motion, auto-acoustics of the throttle, the stutter of brake lights. But it’s suspended, held in oil. The driving becomes a dream, a route to notice rather than to escape.

Conversely, Abandoned Canyon Plaza shows a strip mall after dark, parking lot empty save for one old sedan and a wobbling dumpster at the corner. Fluorescent bulbs in the storefronts hum coldly. There’s no movement—none—but you feel the afterlife of motion: the late-night snack crew, the early shift caretakers. Park is not romanticizing vacancy—she’s pointing out that even emptiness is layered.

Light in Park’s work is an interior map. In Noontime Overpass, she bathes a freeway bridge in high sun: white sky, steel beams casting short shadows across a scaffolded underpass. But look closer—sunlight wipes the red of taillights left in idle, flickering across the asphalt cracks. The color palette is restrained—pinks, silvery glimmers, cream, dark grays—but intentional: white stucco walls take on flesh in the heat. The paint is almost dry; the city bleaches quietly.

Then there’s Evening in Little Bangladesh, in which Park captures the hot lanterns of outdoor food vendors, steam drifting, bricks glowing rust-red. The air is thick with spices just beyond the frame. You don’t smell it—but your senses know it’s there. She gives structure to a feeling: the knowing that home is a constellation of sensory cues—flavors, lights, ease.

Park navigates color literately, as if the city is typing her a letter. The tawny walls, the flat pink stucco, the washed-out aqua of a trailer home, the rough ochre of street dirt—they speak of layered histories. Each hue is a sentence in a story of migration and settlement.

One of the most moving works is Men at Work – Warehouse District. Three men, maybe four, in fluorescent jackets stand around an open truck back. One points to a stack of boxes in the distance. Park paints the spray-can effect of safety yellow reflecting off corrugated metal. She isn’t interested in drama—these are mundane gestures: loading, stacking, arranging. Yet the painting is reverent. The men’s stances—stable, leaning, gesturing—are elements of a graceful choreography: routine, yes, but also dignity embodied.

Park is drawn to threshold spaces—places where public and private blur. In Parking Lot Baptism, she paints a folding chair set outside a makeshift booth—perhaps a pop-up tax-preparation service or immigrant-advocacy group. Sheets of paper are stacked, pens clutter the table, a tent overhead. No crowd surrounds it. But the scene is pregnant with possibilities: next week, crowd. Tomorrow, conversation. Today, anticipation.

Similarly, Evening Laundry shows a laundromat at dusk. Fluorescent light drips from the ceiling onto washers inside. Through the glass, you see men loading soap, women feeding quarters. Park zooms in on reflective wet clothes, the gleam of stainless steel lids, bits of lint. Then, outside, a car idles by, lights on, driver waiting. It’s everyday, but its energy hums.

A “token” element in Park’s art is objects. Carts stacked by a storepreneur, plastic crates half-filled with sodas, tarps flapping in breeze—these are characters. In Extension Cord Tangles, she paints a coil of neon-orange cord snaking across a dusty backlot, tied to a lamp circuit hanging on a sagging telephone pole. It’s absurd, technical, vulnerable. But it’s alive. Without cables and tarps, none of the other scenes would exist. These ribbons are connective tissue. They are the unsung tools—just as critical as people.

Another object scene: Clipboards at Dawn. Three clipboards sit atop a High Sierra cooler leaning up against a white wall. Each board bears handwritten forms, fold lines, coffee stains. Three pens lay diagonally across. Park paints the fiberglass walls and gritty cement in a tonal hush. It’s just morning readiness—but the painting feels holy, holding a minute of preparation in suspension.

The show reminds you: immigrant communities often bootstrap economies: street vending, salon sits, household studios. In Carwindshield Shade – Hair Salon Next Door, she documents a car parked against a storefront. The sunshade reflects back pink salon lamps. Inside, you glimpse a stylist’s mirror, a wrapped gift bag, an unattended comb. Park isn’t exposing a backdoor operation—but she’s noticing a boundary: what’s private-public, home-business, visible-invisible. That dichotomy fascinates her.

Another painting, Dolls & Boots, shows a small shop window: plastic princess dolls, rubber rainboots lined in neat rows, a tiny handwritten sign reading “20% Off First Week.” The retail is modest, but Park accents a neon reflection in the glass—an echo of license around the corner. These windows are rhetorical: speak of hope, show of identity, pitch of enterprise.

Park acquires nuance through repetition. In fifteen paintings, you see facades with bilingual text. In ten, you see vehicles. In eight, streetlights and parking lots. None feels redundant; each layer accumulates in memory. As you leave the gallery, you realize you’ve absorbed a portrait not of LA’s iconic wealth, but of its quietly radiant variety—those neighborhoods made by unrecognized labor, survival, and ordinary love.

Park never prepends captions to contextualize. She trusts viewers to recognize the monumentality of the normal. This is assured artistry: to treat dust-covered parking stripes as canvas, to paint asphalt lines as if they were brush marks in the great rivers of Picasso.

Of Our Own premiered June 21, 2025, and runs through July 29, 2025. In that timeframe, the shows’ timing is meaningful. Southern California has recently seen spikes in ICE activity—raids, detentions, anxiety within immigrant families. Park’s paintings become repositories of calm. They stake presence: we are here, we built this. We nourish. We persist. That insistence isn’t loud; it’s courageous. It’s a meditation in color and scale.

The gallery’s press release notes that Park “[reshapes] the visual discourse to center immigrant labor, love, and informal economies. -It is accurate. These are quiet affirmations. Not exposes. Not selfies. Not celebratory circus. But precisely the brush strokes that say: we are part of the frame. We are not “other.” We are of here.

No comments yet.