In the hierarchy of American art institutions, graffiti has long existed as a subject more to be studied than celebrated, policed rather than preserved. But in Above Ground: Art from the Martin Wong Graffiti Collection, now on view at the Museum of the City of New York, we are confronted with a vivid reversal: graffiti not only enters the canon—it rewrites it.

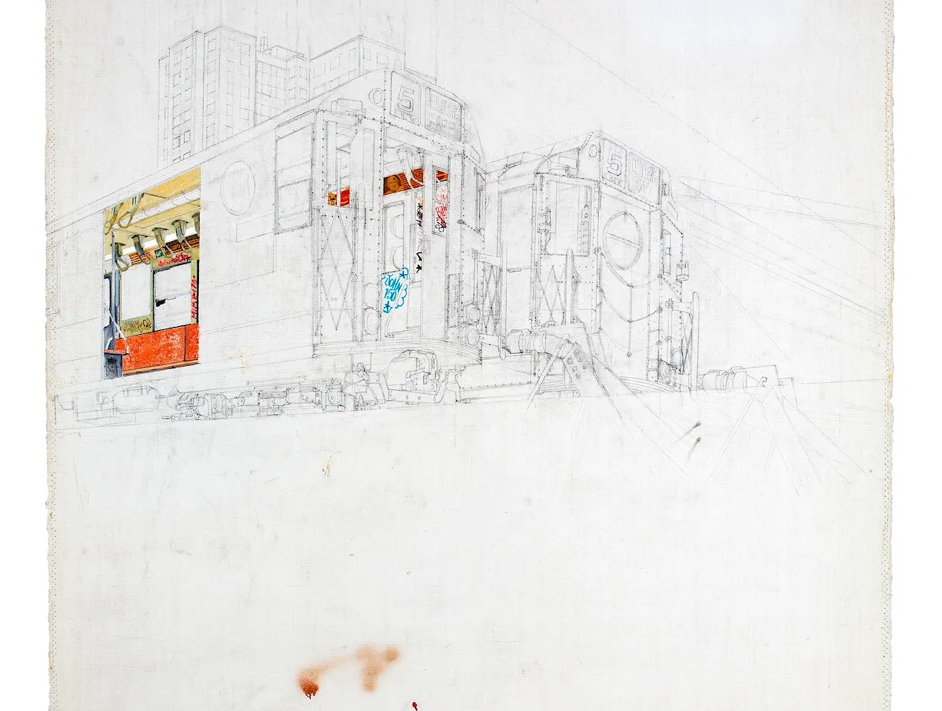

Running from November 22, 2024, through August 10, 2025, this landmark exhibition brings to light the most important private archive of graffiti art ever assembled. Collected by painter and cultural visionary Martin Wong, the works on view include original canvases, sketchbooks, photographs, blackbook drawings, jackets, subway map collages, and handwritten ephemera—offering a rare, electrifying portrait of the early years of New York City graffiti.

But more than just a timeline of tags or a museumified spray can hall of fame, Above Ground is an act of translation—of turning the ephemeral into the eternal, of elevating street voices to museum walls without sterilizing their defiance.

Martin Wong: A Collector with Skin in the Game

To understand Above Ground, one must first understand Martin Wong (1946–1999). Born in San Francisco and based in New York’s Lower East Side, Wong was a painter best known for his poetic renderings of cityscapes and marginalized lives. But beneath his painterly sensibility lay an anthropologist’s eye, a lifelong reverence for the codes and rituals of subcultures.

Wong began collecting graffiti ephemera in the early 1980s, not out of trend or market potential, but out of profound respect. He befriended writers, traded canvases, and preserved works others saw as disposable. He didn’t just admire the form—he saw the artists as peers, as cultural historians working in aerosol instead of oil.

His collection, now held by the Museum of the City of New York, consists of over 300 pieces created by more than 100 artists, among them: LA2, Daze, Zephyr, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, Futura, Rammellzee, Crash, Noc 167, and many more. These are the architects of wildstyle, the abstract expressionists of transit lines, the unsung originators of a global visual language.

Entering the Archive: A Museum Reclaimed

Walking into Above Ground feels less like entering a gallery and more like entering a dimensional blueprint of 1980s New York. The exhibition design leans into the texture of the period—subway tile facades, chain-link partitions, hand-pasted wheat posters—all used to frame the artwork without aestheticizing it.

The works, which range from subway-map paintings to spray-can studies and marker-tagged letterheads, don’t sit quietly. They hum with motion, urgency, and adolescent genius. It’s not a history lesson—it’s a living memory.

From Zephyr’s curved alphabets to Lady Pink’s feminist insurgencies to the cosmic mythologies of Rammellzee, the collection pulses with the raw, experimental energy of writers who were constructing identity through letterforms. Graffiti was not simply a name scrawled in haste—it was the public performance of selfhood.

And Wong, ever the cultural empath, saved it not to own it, but to prevent its erasure.

Above Ground, but Never Sanitized

The phrase “above ground” in graffiti culture implies visibility—moving from subways and alleyways to walls, canvases, and ultimately, legitimacy. But visibility is a double-edged sword. Too often, graffiti’s entrance into galleries and institutions comes with compromise: aesthetic decontextualization, commercial neutering, or sheer tokenism.

This exhibition refuses that. Curated by Sean Corcoran and the museum’s graffiti research team, Above Ground doesn’t just place graffiti on par with fine art—it insists that it has always been art. And it goes a step further: it demands that we view it on its own terms.

There are no overwrought artist statements, no press releases about “street meets chic.” Instead, there are oral histories, sketchbooks annotated by the artists themselves, and vitrines filled with subway maps, letter exchanges, and Polaroids of works long since buffed out.

In doing so, the show captures the fragility and ferocity of a form that was never meant to last—but refused to be forgotten.

The Politics of Preservation

Wong’s collection gains added resonance when considered through the lens of erasure—both systemic and spatial. During the very years these works were being created, the city was waging war on graffiti. Transit authorities buffed trains daily. Mayors vowed crackdowns. Police targeted young Black and Latino teens whose only crime was claiming visibility.

In this climate, what Wong did was radical. He didn’t just collect art—he collected lives, stories, resistance. His archive is now a counter-narrative to state control, a monument to what city institutions tried to scrub away.

This context matters. Without it, graffiti becomes just “urban flavor.” With it, we see the collection for what it truly is: a resistance archive, a visual ledger of youth culture challenging urban decay, police brutality, racial marginalization, and capitalist enclosure.

Blackbooks and Blueprints: The Writing Behind the Writing

Some of the exhibition’s most intimate pieces aren’t bombed canvases or murals but blackbooks—those sacred sketchbooks passed among writers like sacred texts. These contain early drafts of tags, letters to other writers, notes on paint chemistry, and coded messages about turf wars and train yards.

Blackbooks are the blueprint behind the art, and here, they’re treated with the reverence they deserve. In one case, a blackbook from 1981 belonging to DAZE features side-by-side sketches that later became full-scale pieces—proof that graffiti, often seen as impulsive, was in fact carefully constructed performance.

Another standout: a subway map tagged over by multiple writers—an ephemeral collaboration that took place over months and across boroughs, each participant layering their mark over another. It’s a metaphor for the entire show: graffiti as polyphonic memory, as democratic art form.

Legacy Without Fossilization

The ultimate triumph of Above Ground is its refusal to fossilize graffiti. Too often, when street culture enters institutions, it becomes embalmed—trapped in a white cube, silenced by reverence. Not here.

The works on view retain their restlessness, their coded joy, their adolescent brashness. You don’t just see style—you see speed, fear, confidence, play, and rebellion. You see kids claiming space in a city that offered them none.

More than 40 years after their creation, these works still crackle. And that’s thanks to Martin Wong—not because he predicted their market value, but because he saw their intrinsic worth. He saw not “graffiti” but art, not “vandals” but authors.

Impression

At its best, a museum doesn’t just show you art—it shows you why art matters. Above Ground does just that. It doesn’t simply present graffiti as aesthetic—it offers it as evidence of presence, of persistence, of pride.

Martin Wong may no longer be here to watch the writers he championed take their rightful place in the canon. But the show speaks for him, and through him, for every kid who ever sprayed their name in the dark hoping someone might see it in the morning light.

No comments yet.