In Hong Kong, WOAW Gallery’s latest exhibition explores not just the face of Braun’s iconic designs, but the technological soul within.

The sleek simplicity of Braun’s designs has long made them touchstones of industrial design history. Clocks, razors, radios, mixers—mundane objects made beautiful through radical restraint. Braun, particularly under the creative direction of Dieter Rams, transformed the way consumer products looked, felt, and functioned. It was never just about minimalism. It was about purpose. Every surface, dial, and edge was intentional. No more, no less.

The impression of that approach can still be seen everywhere: in Apple’s clean lines, in Ikea’s utilitarian elegance, in Muji’s no-logo clarity. Braun’s DNA runs deep through 21st-century product design. Which is why it’s hardly surprising that the brand remains in the crosshairs of cultural retrospectives, academic studies, design documentaries, and, most recently, Hong Kong’s WOAW Gallery.

Their exhibition, titled “Honest Machines,” doesn’t just celebrate Braun’s aesthetics—it dissects them. It asks a deeper question: what lies beneath that iconic shell?

The Myth and the Machine

“Honest Machines” positions itself as more than a nostalgic victory lap for mid-century modernism. Instead, it dives into the philosophical and mechanical inner workings of Braun’s designs. It acknowledges that these objects were not just beautiful forms—they were revolutionary machines in themselves. Devices that hid complexity behind clarity. That demanded discipline from designers so that users wouldn’t have to suffer it.

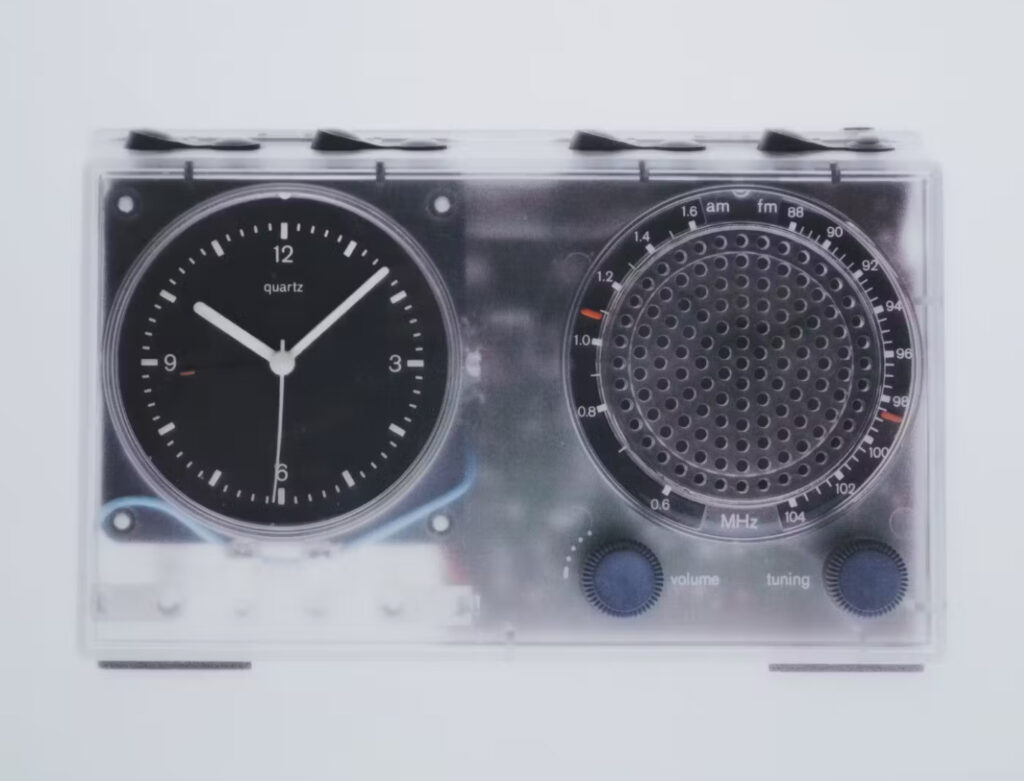

At the heart of the show is an attempt to reconcile how Braun’s stripped-back forms housed emerging technologies that were anything but simple. The transistor radios of the 1950s. The electric razors of the 1960s. The ergonomic, compact, battery-powered travel clocks. They were marvels of engineering, just as much as they were examples of restraint in design.

WOAW’s exhibition doesn’t ignore this complexity. In fact, it invites visitors to engage with the tension between outside and inside. Many of the pieces on display are shown in disassembled or x-ray forms—highlighting the clever circuitry and engineering choices that made their simplicity possible.

The Rams Effect

Any conversation about Braun invariably circles back to Dieter Rams, the legendary designer who joined the company in 1955 and reshaped its visual and philosophical identity. Rams’ “Ten Principles of Good Design” have achieved near-canonical status among designers, shaping decades of work across industries.

Those principles—good design is innovative, useful, aesthetic, understandable, unobtrusive, honest, long-lasting, thorough, environmentally friendly, and involves as little design as possible—are more than a manifesto. They’re the bedrock of Braun’s visual language. And more than half a century later, they still read as radical.

WOAW’s curatorial team recognizes this. But instead of simply quoting Rams, the exhibition builds a dialogue with his legacy. Some installations challenge the idea that form can ever be truly “neutral” or “invisible.” Others celebrate it. In one corner, you’ll find a wall of archival Braun advertising—beautifully photographed, gorgeously typeset, and completely devoid of gimmick. In another, a torn-down SK 61 record player, laid out like an anatomical study, its Bauhaus-inspired logic fully exposed.

Objects That Work (and Still Work)

What makes Braun’s work even more remarkable is that most of it still functions. In an era where planned obsolescence is baked into product cycles, Braun’s creations endure. Not just physically, but culturally. Vintage collectors on eBay pay a premium for clean T3 pocket radios and early electric razors. Museums fight over early examples of the TP1 portable record player. And you’ll still find Braun wall clocks keeping time in boutique hotels and design studios around the world.

The exhibition leans into this idea of functional longevity. These weren’t precious, untouchable objects. They were made to be used. And that use is what shaped their form. Each product in “Honest Machines” tells a story not just of how it was made, but how it was meant to be used.

Visitors are encouraged to interact with replicas, open sliding mechanisms, press buttons, wind knobs. The tactility of these designs is central to their appeal. Even now, decades later, there’s a calming logic to the way Braun products operate. Nothing is hidden without reason. Nothing added without function.

Braun vs. Now: A Mirror to Modern Consumerism

One of the more provocative aspects of the exhibition is its mirror held up to today’s design culture. We live in an age of maximalism masquerading as minimalism—where clean aesthetics often mask cluttered user experiences, addictive interfaces, and ethically murky production methods.

“Honest Machines” doesn’t shy away from this comparison. In fact, it weaponizes it. Side-by-side installations pit Braun products against their modern counterparts—razors with a dozen blades, radios covered in branding, clocks that do too much and not enough.

The result is a quiet but powerful indictment of how “simplicity” has been commodified and distorted. It asks: is our obsession with “clean design” actually honest? Or is it just aesthetic white noise?

By contrast, Braun’s honesty wasn’t in how things looked—but how they worked. That commitment to clarity, transparency, and utility wasn’t a marketing ploy. It was a worldview.

Cultural Reverberations

If the average consumer doesn’t know Braun’s full backstory, they’ve still felt its impression. Most notably, through Apple, where design chief Jony Ive often cited Rams as a direct influence. The symmetry of the iPod, the whiteness of the iMac, the grid-based logic of iOS—all draw from Braun’s visual grammar.

But Braun’s influence goes even further. Fashion brands like A.P.C. and COS mirror its aesthetic economy. Sound designers and interface engineers cite its clarity as foundational. Even the modern rise of “quiet luxury” can be traced, in part, back to Braun’s refusal to shout.

WOAW’s exhibition touches on these cultural threads. One installation maps Braun’s visual influence through decades of consumer products, from early mobile phones to smart speakers. It’s a design family tree—and Braun is undeniably the root.

The Philosophy Behind the Plastic

Braun’s brilliance wasn’t in exotic materials or complex manufacturing. It was often in its restraint: the matte plastic casing of a clock, the soft taper of a button, the just-right angle of a radio dial. It’s in these subtle gestures that Braun expressed its worldview. A worldview rooted in clarity, responsibility, and the dignity of function.

And perhaps most importantly: respect for the user. Braun assumed people were smart. That they didn’t need bells and whistles to be impressed. That they could appreciate good design not because it screamed at them, but because it helped them live a little better.

This is a hard thing to translate into an exhibition, but “Honest Machines” does it well. Through minimal scenography, strong lighting, and generous white space, it lets the products speak for themselves—much as Braun always intended.

Beyond Nostalgia

What makes “Honest Machines” truly worthwhile is that it doesn’t romanticize Braun. It respects it. It interrogates it. It acknowledges that even simplicity can be a kind of ideology. That even honesty, as a design principle, is culturally specific and historically situated.

The show resists turning Braun into a museum piece. Instead, it asks: what would happen if we applied the same standards to the devices we design today? Would they pass the test?

WOAW has created something more than a love letter to Dieter Rams. It’s a design morality tale. A reminder that how something looks is only half the story. The other half is how it works—and why.

Why Braun Still Matters

In the cluttered chaos of modern consumer life, Braun’s legacy stands as a beacon of clarity. Not because it was perfect, but because it cared. About the user. About the object. About the purpose.

That’s what “Honest Machines” captures so effectively. It doesn’t just tell us Braun was important. It shows us why. It opens up these designs like time capsules and reminds us what good design looks like—and what it feels like.

No comments yet.