In 2014, American visual artist Robert Longo stood at a crossroad of retrospection and reinvention. Known globally for his charcoal-drenched hyperrealism and provocative sociopolitical commentary, Longo had already spent over three decades redefining the edge between fine art and the image politics of power, protest, and spectacle. But 2014 was not just another year in his prolific timeline—it marked a convergence of urgency and vision that extended from gallery walls to the fractured nerves of a nation under surveillance, unrest, and polarization. This was Longo in full command of his tools, staring down the black-and-white truth of America through smudged charcoal and stark cultural reckoning.

An American in Monochrome: Setting the Scene

In 2014, Longo unveiled a body of work that intensified his long-held obsession with authority and vulnerability. His solo show “Gang of Cosmos” at Metro Pictures Gallery in New York displayed monumental charcoal drawings based on Abstract Expressionist masterpieces. It was a daring act—recreating, by hand, the works of artists like Pollock, Rothko, and Krasner, with Longo’s signature commitment to illusionism. Each drawing was painstakingly rendered, not as parody or homage, but as confrontation.

Why replicate paintings in black and white? Why distill the chaotic gesturalism of color into finely rendered dust? For Longo, the answer was clear: this was not reproduction. It was excavation. By removing pigment and framing these canvases in charcoal—a medium associated more with sketchbooks than spectacle—Longo stripped away myth. The energy remained, but it was now spectral, x-rayed, recontextualized.

He wasn’t desecrating the canon. He was interrogating it.

The Politics of Remaking

“Gang of Cosmos” was more than aesthetic provocation. It was a philosophical proposition. In Longo’s hands, Pollock’s “Number 1A” became a site of tension: once spontaneous, now controlled; once wild, now studied. By redrawing the canonical works of Abstract Expressionists—many of whom were lionized as uniquely American, white, and male—Longo asked: what power structures persist in art history? What is worth preserving, and what requires revision?

By 2014, the art world was reckoning with its own institutional biases—race, gender, access, and legacy—and Longo’s reimagining of the mid-century canon functioned as both gesture and critique. He did not attack his predecessors, but neither did he reify them. He held their work at arm’s length, reproduced their most primal moments in meticulously controlled handwork, and forced the viewer to feel the tension between admiration and unease.

This was typical Longo: never content to present an image without embedding it in a dialectic. His renderings are always psychological. Every drawing is an X-ray of America’s conscience.

Charcoal as Weaponry

By 2014, Longo’s charcoal had matured from medium to methodology. Across various series—from his Men in the Cities drawings of flailing businessmen in the 1980s, to his more recent renderings of waves, gun barrels, and flag-draped coffins—charcoal remained his brush, his weapon, his eraser, and his mirror.

The monumental works of 2014 were no different. Using paper the size of walls, Longo layered black upon black, detail upon absence, to create images so precise they read as photographs from afar. But these were not photorealism for spectacle’s sake. They were mnemonic devices—inviting us to remember, to see again what has been flattened by media fatigue.

His drawings of riot police, courtrooms, and missiles in mid-air operate as elegies and indictments. They are deeply moral, yet never moralizing. In one image, an American flag ripples violently in front of riot shields. In another, a wave—seemingly still—carries the weight of tsunamic force. These are not just symbols; they are systems.

Longo’s charcoal doesn’t simply show. It asks—Where is the edge between beauty and terror? What remains invisible in the hyper-visibility of surveillance culture?

The Ferguson Moment

2014 was also the year Michael Brown was shot and killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri. The event, and the subsequent protests and state response, brought questions of racial justice, law enforcement, and militarization to the national forefront. Longo, whose work had long circled themes of state power, resistance, and collective memory, responded—not with didacticism but with empathy channeled through imagery.

While not all of his works from that year directly reference Ferguson, the ethos of unrest—of citizens demanding to be seen—permeates his practice. Longo’s black-and-white aesthetic becomes metaphor: the world is not gray when it comes to injustice. His images, drained of color, pulse with moral clarity.

In this context, even his replication of Abstract Expressionist works takes on a political dimension. Abstract Expressionism was, after all, championed by the U.S. government during the Cold War as a symbol of American freedom. Longo’s monochromatic redrawings confront this legacy, asking: Whose freedom was championed? Who was excluded from the gesture?

Studio as War Room

Longo’s Brooklyn studio in 2014 resembled a war room more than a traditional atelier. Teams of assistants helped him manage the scale of his output, but every mark, every smudge was meticulously approved or placed by Longo himself. His process was forensic. Images were sourced from archival footage, news reports, and journalistic photography. He spoke often of the difficulty of choosing which images to draw—how to honor a moment, how to depict horror without sensationalizing it.

In his interview with Artforum that year, he reflected:

“There’s a responsibility in taking images that are already soaked in meaning and trying to make them more visible. The world doesn’t need more pictures—it needs pictures that stop you.”

Longo never claimed neutrality. He knew his work could not escape context. The sheer size of his drawings—the fact that they loomed over viewers like architectural structures—forced spectators into confrontation. You could not glance. You had to reckon.

The Black Square and the Human Skull

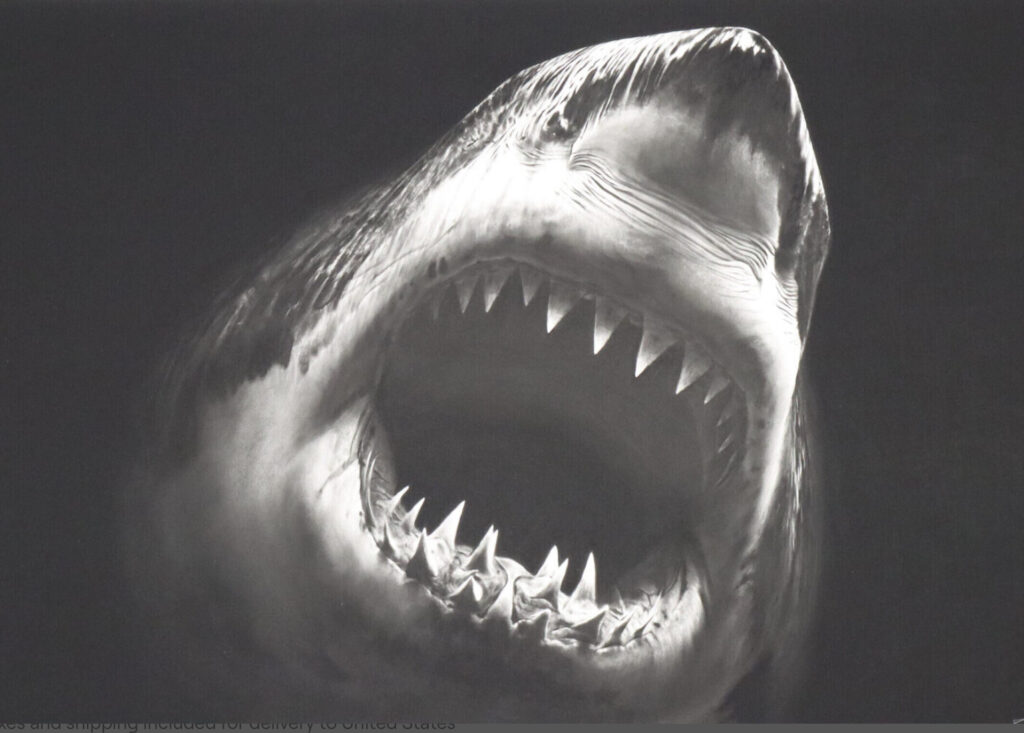

One of Longo’s most haunting motifs in 2014 was his recurring reference to the black square—a nod to Kazimir Malevich, but also to voids, tombstones, and television screens gone dark. In works like Untitled (The Skull) and Death Star, Longo used the motif as a frame through which to examine mortality, anonymity, and spectacle.

In a year where the public square was both physical and digital—Ferguson’s streets mirrored on Twitter feeds—Longo’s blackened squares seemed prophetic. They represented absence and omnipresence. The protest and the broadcast. The image and the erasure.

Even his portraits of the U.S. Supreme Court in session, rendered in chilling realism, seem cloaked in black square logic. Authority is not shown as virtuous, but as frozen. Power, in Longo’s hands, is not luminous. It is dense, heavy, and opaque.

Legacy and Longing

By 2014, Robert Longo had already earned his place among America’s foremost visual voices. His transition from the punkish postmodernism of the 1980s into the politically attuned gravitas of his later years was complete. But unlike some of his contemporaries who mellowed into abstraction or self-referentiality, Longo’s work only grew more urgent.

He never abandoned the belief that art could intervene—that an image, rightly constructed, could cut through noise. And in 2014, with America at the cusp of protest and polarization, his drawings became tools for slow seeing. A riot shield. A flag. A Pollock painting. A skull. Each rendered with a surgeon’s care, each demanding more than a scroll or swipe.

Conclusion: The Weight of the Real

Robert Longo’s 2014 output cannot be reduced to one show, one drawing, or one theme. It was a mosaic of obsessions and responsibilities—a testimony to an artist refusing to flinch in the face of history’s rough edge. Whether interrogating the canon through “Gang of Cosmos,” amplifying unrest through riot imagery, or rendering the fragile architecture of authority in courtrooms and skulls, Longo made one thing clear:

The real is not enough. It must be seen again—darker, slower, deeper.

And in 2014, in the shadow of tear gas, retro canonization, and institutional scrutiny, Robert Longo gave us not simply drawings—but memorials in dust, truth in silhouette, and the clearest mirror we may ever receive.

No comments yet.