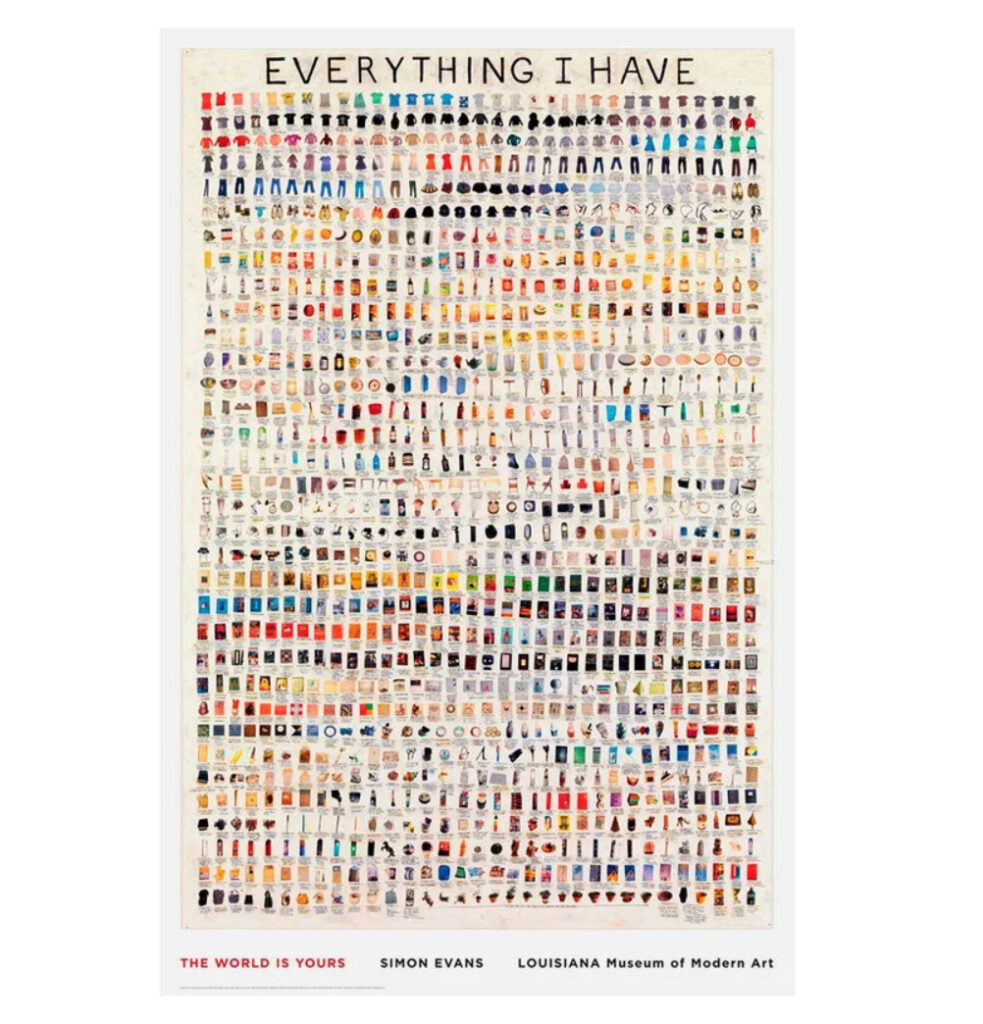

Tucked into the cool modernist curves of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark hangs a deceptively simple poster. Everything I Have by Simon Evans is more than just wall décor. It’s a life inventory, a visual confession, and a quiet act of radical transparency. Composed of hundreds—nearly a thousand—intricate, handwritten and hand-drawn miniatures, the work catalogs every single possession the artist owned at the time.

Displayed as part of the 2009 international group exhibition The World is Yours, the piece did not shout for attention. But it lingered. And now, as part of the Louisiana’s growing collection of poster art, Everything I Have continues to resonate beyond its original installation. Printed on fine paper, framed on walls far from Denmark, the work invites viewers to ask: What would our own inventories reveal?

In an age of overconsumption, digital identity, and curated perfection, Simon Evans offers a raw and literal accounting. It’s both art and artifact. And in revisiting the poster today, we find it speaking louder than ever.

Who Is Simon Evans?

Simon Evans is not one person. He is two. The name refers to the follow-up work of Simon Evans and Sarah Lannan, a duo based in Brooklyn. Originally trained as a writer, Simon began creating text-based visual works that bridge the line between drawing, list-making, and poetry. Sarah, trained in painting, joined his practice in 2001 and helped refine the visual rigor of their pieces.

Their work is often confessional, meticulous, and filled with dark humor. It draws on the tradition of outsider art, conceptual mapping, and obsessive cataloging. Evans’s art feels simultaneously like a personal diary and a bureaucratic record. His obsessive listings—of thoughts, possessions, anxieties, regrets—mirror the internal spirals of the modern psyche.

Everything I Have is perhaps their most iconic example of this approach.

The Art of the Inventory

The poster is exactly what the title promises: a meticulous visual list of every item in the artist’s possession at the time of its creation. There are no editorialized choices, no attempts at aesthetic curation. Toothbrush. Keys. Receipts. Books. Shoes. A broken umbrella. Socks. Each item is hand-drawn in miniature and labeled in the artist’s tight, precise scrawl.

What’s fascinating is not just the volume, but the banality. Most of the items are completely unremarkable. But together, they build a portrait more intimate than any photograph. You come to understand the artist through his objects—his clutter, his organization, his needs, his nostalgia.

It is, in essence, a reverse self-portrait.

The Power of the Mundane

In a world that celebrates the extraordinary, Everything I Have finds power in the mundane. It makes no distinction between an iPod and a half-used pen. It does not prioritize function, value, or sentiment. Every object is equal on the page.

There’s something quietly radical in that. We live surrounded by things we do not notice. Evans forces us to look again. To see the weight of ownership, and perhaps more importantly, the weight of accumulation. What does it mean to have so much? And what does it say about who we are?

The work resists the minimalist fantasy that art—and life—should be clean and curated. It embraces the mess.

The Louisiana Context: A Museum of Living Thought

The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art has long positioned itself as more than a repository of fine art. Located on the coast north of Copenhagen, it blends landscape, architecture, and curation into a deeply reflective experience. Its exhibitions are global but grounded, progressive but human.

In 2009, the museum mounted The World is Yours, a sweeping contemporary exhibition featuring more than 20 artists from around the world. The show explored identity, globalization, and the politics of personal space. Everything I Have fit neatly into that framework—inviting viewers to contemplate personal identity in a commodified world.

While some works in the exhibition took on geopolitical scope, Evans zoomed in—to the level of a shoelace, a paperclip. And yet, his focus felt no less grand.

Posters as Memory and Medium

The Louisiana Museum’s poster collection is renowned. Unlike many museums that treat posters as mere promotional tools, Louisiana preserves and curates them as artworks in their own right. Their posters don’t just sell shows; they sustain them.

Printed on high-quality paper and often reissued in limited runs, the museum’s posters are collected not just by art lovers but by those who want to live with a piece of cultural memory.

The Everything I Have poster, when framed, feels like a window into a moment in time—not just in the artist’s life, but in your own. There’s an uncanny effect that takes place when you hang the inventory of a stranger on your wall: you begin to see yourself in it.

Art, Possession, and the Modern Condition

What does it mean to own something? To hold it, to claim it, to be responsible for it?

Evans’s piece is a quiet meditation on ownership. It doesn’t moralize. But it makes the act of possession visible in a way that feels both absurd and touching. We often think of ourselves as more than our things—but try living without them. Try defining yourself without your tools, your books, your shoes.

In that sense, Everything I Have is a statement of vulnerability. It says: Here I am. Entirely. Nothing hidden. Nothing elevated. Just everything I have.

In the Silhouette of Consumerism

There’s a reason this poster has aged so well. Since 2009, our relationship with objects has only grown more complex. The rise of fast fashion, mass consumerism, online shopping, and influencer culture has made it easier than ever to own—and harder than ever to value.

Evans’s work predates Marie Kondo’s decluttering empire. It predates the minimalist Instagram aesthetic. And yet, it offers something more profound than either: not a directive, but a mirror.

It doesn’t tell you to let go. It tells you to look.

Drawing as Documentation

There’s a childlike joy to the piece that shouldn’t be overlooked. The illustrations are simple but full of character. A sock isn’t just a sock—it’s drawn with care. The crumpled wrapper isn’t rushed; it’s rendered with affection.

In that way, the work is less a list and more a love letter. Not to things, per se, but to life in all its cluttered, overstuffed, chaotic glory.

This is not data. This is devotion.

The Art of Self-Surveillance

But there’s also an eerie aspect to the work. It recalls the language of surveillance, of border declarations, of customs forms and police reports. The very act of cataloging the self turns the artist into his own observer. A bureaucrat of the soul.

In doing so, Everything I Have anticipates the era of digital quantification—of screen time reports, step counts, data mining. It asks: what happens when we reduce ourselves to lists? To numbers?

The answer, in this case, is unexpectedly tender.

Framing the Everyday

When viewers buy the Louisiana Museum poster of Everything I Have, they’re doing more than decorating. They’re choosing to bring someone else’s inner world into their own space. They’re framing everyday life and calling it art.

And rightly so. Evans reminds us that art doesn’t have to be sublime or monumental. It can be found in the bottom of your backpack. On the corner of your desk. In the pile of things you keep meaning to throw away.

A Final Tally

We all carry an inventory. Some of us write it down. Most of us live with it quietly, unconsciously. But Simon Evans turned that inventory into art. And in doing so, he offered a radical invitation: to see the ordinary as worthy, the overlooked as intimate, and the sum of our possessions as a kind of self-portrait.

As the Louisiana Museum reissues its posters and more people bring Everything I Have into their homes, the work finds a new kind of life—on new walls, in new contexts, for new eyes.

We live in a time of curated identities and performative minimalism. Against that backdrop, Evans’s honest accounting feels revolutionary. He did not seek to impress. He sought to record. And in doing so, he left us with something deeply human: a map of a life, drawn one object at a time.

No comments yet.