In 1964, Andy Warhol unveiled Brillo Box, a work that would challenge the very foundation of what people understood as art. It wasn’t a painting or a sculpture in the traditional sense—it was a near-identical reproduction of commercial packaging, a mass-produced commodity that suddenly found itself on a gallery floor instead of a supermarket shelf.

Through Brillo Box, Warhol blurred the line between high art and consumer culture, asking questions that remain fiercely debated: What makes something art? Who decides? And what happens when art becomes indistinguishable from the commercial world it critiques?

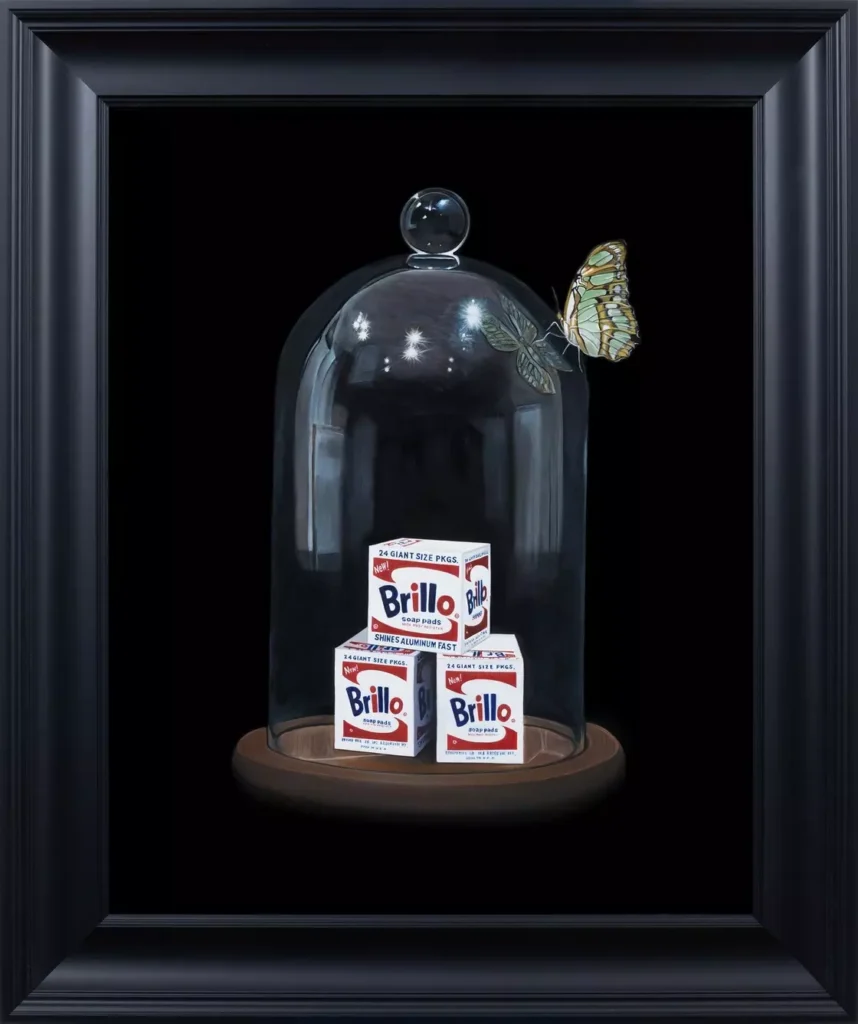

Now, decades later, in an era where the commodification of art has reached unimaginable heights—through NFTs, AI-generated imagery, and the omnipresence of branding—Warhol’s Brillo finds itself reinterpreted, resurrected, or perhaps reincarnated. Enter Warhol Deux: a contemporary iteration of Warhol’s consumerist critique, where art and commerce continue their cyclical dance.

Brillo Then: Warhol and the Art of Reproduction

To understand Warhol Deux, one must first revisit the original Brillo Box. Warhol, a figure whose very persona embodied the mechanization of art, sought to erase the distinction between the artist’s hand and the factory assembly line. His silkscreened portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Elvis Presley turned Hollywood idols into flat, mass-produced images, just as his Campbell’s Soup Cans transformed a grocery-store staple into a museum-worthy icon.

But Brillo Box was a different kind of provocation. Unlike his earlier works, which replicated images through printmaking, Brillo Box replicated an actual object. The only thing distinguishing Warhol’s box from a real Brillo package was its placement: instead of a store shelf, it sat in a gallery.

Art critic Arthur Danto famously declared that Brillo Box signaled the end of art’s history—not in the sense that art would cease to exist, but rather that the boundaries defining what art could be had collapsed. After Warhol, a piece of commercial packaging, a banana taped to a wall, or even an AI-generated image could all be art, provided they were framed as such.

Brillo Now: Warhol Deux and the Commodification of Everything

Fast-forward to today. The art world no longer merely blurs the line between commerce and creativity—it has obliterated it. Artists collect with brands, corporations commission murals to soften their capitalist edges, and social media influencers turn themselves into walking advertisements.

In this hyper-commercialized landscape, Warhol Deux emerges not just as an homage to Brillo Box, but as an evolution of its critique.

Imagine a gallery filled with modern interpretations of the Brillo aesthetic:

•A set of neon-lit NFT Brillo Boxes, each with a unique blockchain signature, turning Warhol’s concept into a purely digital commodity.

•A sculptural installation of Amazon-branded boxes, stacked high, mimicking the retail ubiquity that Warhol once parodied.

•AI-generated Brillo advertisements, where machine-learning algorithms remix Warhol’s style into infinite, algorithmically curated variations.

Here, Brillo Deux is not just a celebration of Warhol’s legacy—it is a statement on the new age of reproduction, where art is infinitely replicable, yet still retains economic and cultural value.

The Factory, Revived: Art in the Age of AI and Automation

Warhol’s infamous Factory was more than just an artist’s studio; it was an assembly line, a pop-culture incubator, and an experiment in mass production. The Factory employed assistants to create silkscreens, produce films, and generate art at a scale never before seen. Warhol was not just an artist—he was a brand manager, an orchestrator of artistic labor.

Today, the concept of the Factory has been fully realized in the digital sphere. AI-generated art tools like DALL·E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion function as contemporary versions of Warhol’s assistants, producing countless images in seconds. Just as Warhol embraced mechanical processes to remove the artist’s hand, AI now removes the artist entirely.

Warhol Deux asks: If Warhol’s Brillo Boxes questioned the authenticity of art in 1964, what would he make of a world where an algorithm can create a Brillo-inspired masterpiece in milliseconds?

Would Warhol embrace AI as his new Factory? Or would he see it as the final step in the commodification of creativity, where even artistic labor is fully automated?

Brillo Forever: The Future of Art and Consumerism

Despite its origins as a critique of consumerism, Warhol’s Brillo Box ultimately became a collector’s item, selling for millions at auction. Ironically, what once questioned art’s commercial value became one of the most valuable pieces of the 20th century.

The same fate may await Warhol Deux. Whether manifested as physical sculptures, digital NFTs, or AI-generated artworks, it will likely be absorbed into the very market it critiques. The art world, ever-hungry for the next big trend, will commodify even the critique of commodification itself.

And perhaps that is the final, most Warholian irony: no matter how much we try to subvert consumer culture, it always finds a way to package and sell itself.

Impression

If Andy Warhol were alive today, what would he make of Warhol Deux? Would he be fascinated by its digital evolution, the infinite replicability of art, and the blurring of human and machine creativity? Or would he see it as a step too far—a world where even the last remnants of artistic individuality have been dissolved?

No comments yet.