Can a monument turn a myth into a man—or reverse the process?

This is the central, unspoken question at the core of Ngoc Nau’s 2023 experimental video work Virtual Reverie: Echoes of a Forgotten Utopia, a hallucinatory, multi-layered exploration of memory, ideology, and speculative futures. Conceived during the artist’s residency at Rupert in Vilnius, Lithuania, the piece binds together the physical remnants of Soviet-era architecture and political icons with digital landscapes and dance sequences, tracing threads between Vilnius and Hanoi—two cities separated by geography, but historically entangled through ideological background.

Shown most recently at the exhibition “Hypnotising Chickens: Recent Video Art from Vietnam and Tasmania” at Contemporary Art Tasmania, Virtual Reverie belongs to a growing lineage of art that questions the physical and symbolic legacies of socialist utopias through contemporary means. Through the hybrid language of 3D animation, hip-hop mantra, and immersive movement, Ngoc Nau has created a bold visual essay that collapses past and future into a virtual now.

Memory as Landscape, Archive as Architecture

Ngoc Nau’s interest in socialist iconography—particularly in monuments, public sculpture, and their evolving cultural relevance—has long underpinned her work. But in Virtual Reverie, these concerns take on new urgency. With a global wave of decolonization and iconoclasm sweeping through public spaces, Nau asks: What is a monument, if not an ideological interface? What happens when its ideology collapses?

The Lenin statue that once towered over Lukiškės Square in Vilnius is her starting point. Erected during the Soviet occupation and toppled in 1991, the monument was not merely a figure of stone—it was a cipher of authority, meant to shape not just space, but memory. Its removal symbolized a new era, but also left behind a vacuum—an empty plinth of unresolved tension.

By linking this with Hanoi’s own Lenin statue, which still stands in a public park today, Nau performs a transhistorical mapping. Two Lenins, two cities, two timelines. One discarded, one preserved. In her video, these become simulacra, rendered in fragmented 3D animation and inserted into impossible terrains.

Worldbuilding Through Debris

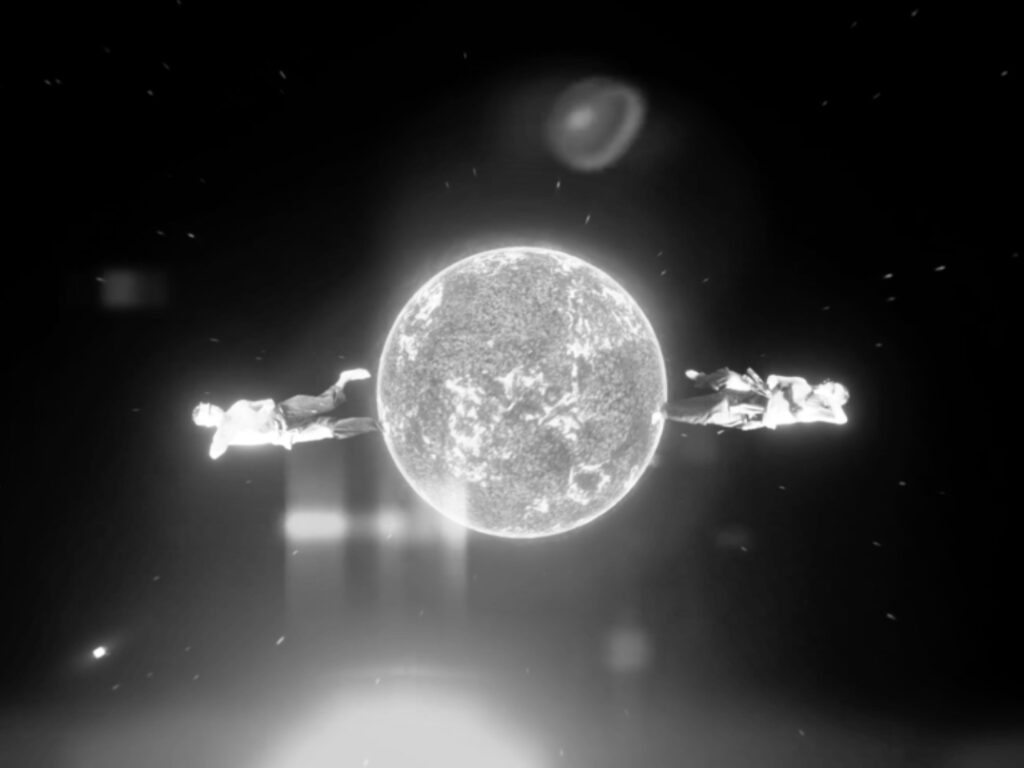

The terrain of Virtual Reverie is not the real world, but something adjacent—a world cobbled from pixels, dreams, and memory shards. Using 3D-rendered debris, architectural fragments from the Vietnam–Soviet Friendship Palace of Culture and Labor, and visual motifs drawn from street-level protest footage, Nau constructs a digital topography where ruins are portals, not endpoints.

The result is a dreamlike, glitched environment, at once post-apocalyptic and speculative. It feels like a place between data dump and daydream—a site where ideological architecture can be repurposed into dance floors, memory archives, or protest arenas. Monuments become mutable; statues can be danced with, ignored, or exploded.

This world is traversed not by politicians or historians, but by young dancers—costumed figures who somersault through collapsed structures, vogue against marble columns, or stand silently among crumbled busts. Their presence acts as a kind of resistance—a generational refusal to remain static, to let past trauma or legacy dominate their physical or psychic space.

Choreography and Reclamation

Movement is central to Virtual Reverie. Ngoc Nau integrates choreography as commentary, allowing the human body to speak where ideology once dominated. The dancers perform in bursts: sometimes synchronized, sometimes chaotic. Their gestures alternate between fluid grace and confrontational energy, embodying both protest and play.

In one sequence, dancers rhythmically orbit a virtual Lenin bust, their shadows glitching against a digital plaza. In another, a breakdancer performs atop a simulated obelisk, pixel particles dispersing around them like shattered relics. These are not random scenes—they’re acts of reclamation, where the body moves freely within spaces once controlled by regime aesthetics.

The performances are not “anti-Lenin,” nor are they nostalgic. Rather, they seem to say: we acknowledge this past, but we will not be bound to it. We move. We glitch. We remix.

Soundtrack: Hip-Hop as History

In parallel with its visuals, Virtual Reverie is anchored by a soundscape of lo-fi hip-hop loops, protest chants, and audio distortion. At times, the soundtrack includes direct samples from the Euromaidan protests in Ukraine (2013–2014), where another Lenin statue met its end. At other points, spoken word tracks—some in Vietnamese, others in English—drift in and out like half-remembered mantras.

These aural layers echo the work’s thesis: ideological echoes persist, even after statues fall. But within that echo, new rhythms emerge. Hip-hop, as a globally adopted language of resistance, becomes the sonic counterpoint to the stillness of statues. The soundtrack never overtakes the visuals, but works in dialogue with them—disrupting nostalgia, refusing silence.

The Politics of Remembrance

Virtual Reverie doesn’t moralize. It doesn’t condemn Soviet history, nor does it glorify its iconography. Instead, it asks viewers to sit in the unease of contradiction. It shows how histories intersect, decay, and transform—not in archives or textbooks, but in lived urban space.

By juxtaposing Vilnius and Hanoi, Nau draws attention to how different cultures absorb and adapt ideological structures. One city removes Lenin. Another preserves him. One erases the statue. Another builds a skate park around it.

What does this tell us? That there is no unified narrative of the past—only pluralities. And these pluralities are shaped by young people, not policymakers. By dancers, not dictators.

A Utopia Forgotten, Reimagined

The subtitle of the piece—Echoes of a Forgotten Utopia—is both ironic and sincere. The “utopia” of socialist internationalism, of cross-cultural solidarity built on labor and equality, may now feel like a ghost. But Nau’s video does not mock that dream. It treats it as a relic worth revisiting, not blindly, but critically.

In Virtual Reverie, utopia is not a place—but a verb. A process. Something that can be reshaped in Blender, remixed in Ableton, and embodied on screen. It is speculative realism for post-socialist subjects—a future not defined by what was, but by what could be.

Exhibition Context: Hypnotising Chickens

Virtual Reverie was recently featured in the show Hypnotising Chickens: Recent Video Art from Vietnam and Tasmania, held from March 13–29, 2025 at Contemporary Art Tasmania. The show explored digital storytelling and site-based identity, using video as both archive and rebellion.

In this context, Nau’s work stood out for its global reach and regional precision. While her aesthetic is universal—glitch, render, loop—the specifics of her research anchor it in real histories. The Lenin statues are not props; they are emblems of contested memory. Her video is not just art—it’s a digital monument of its own.

Past as Playground, Future as Freedom

Ngoc Nau’s Virtual Reverie: Echoes of a Forgotten Utopia is not simply a video installation—it is a re-imagination engine. It transforms abandoned ideology into animated possibility. It lets the body move where it was once surveilled. It lets the monument fall, not into ruin, but into reinterpretation.

In doing so, it becomes a deeply hopeful work. Not because it ignores history, but because it reframes it through motion, rhythm, and imagination. In Nau’s world, the past doesn’t end. It reverberates—pixelated, choreographed, and reprogrammed.

And in those reverberations, we find space—not just to remember, but to dream.

No comments yet.