Walk the streets of New York long enough, and you’ll start noticing patterns. Crushed MetroCards. Lost gloves. Disposable vapes. But for photographer Justin Aversano, it was something smaller, shinier, and far more telling—discarded weed baggies. Hundreds of them.

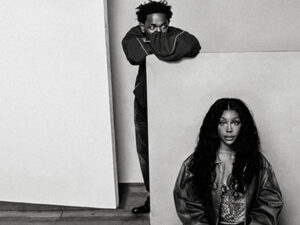

Over the course of several months, Aversano collected over 1,000 empty marijuana baggies from sidewalks, gutters, and stairwells around New York City. Then he did what artists do best—he documented them. What started as a curiosity quickly evolved into a photographic project that says more about urban life, drug culture, and consumer aesthetics than you might expect.

This is not a story about weed. It’s a story about design, trash, normalization, and what our litter says about us.

How It Started: One Baggie on the Sidewalk

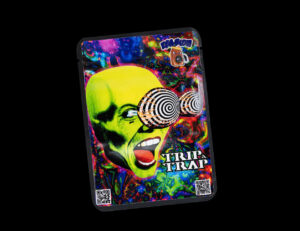

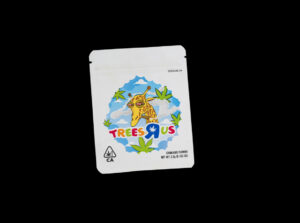

It began casually. One afternoon in Bushwick, Aversano spotted a small, empty bag near a fire hydrant. It wasn’t just any bag—it was colorful, sealed, and covered in graphic art. Cartoon characters, holographic foil, bold fonts. It looked more like candy packaging than something used to sell drugs.

“It was weirdly beautiful,” he said. “And it was just lying there like trash. That contrast hit me—something designed to catch the eye, now stepped on and forgotten.”

He picked it up. Took a photo. Put it in his pocket. A few blocks later, he found another. Then another.

By the end of the week, he had ten. By the end of the month, nearly fifty.

That’s when he realized this wasn’t just garbage. It was a visual language—a code of color, branding, and modern urban commerce—and it was everywhere.

A Portrait of a City in Plastic

The baggies come in every aesthetic imaginable. Some are minimal and sleek, using all-black matte finishes with gothic type. Others go full maximalist: rainbow fonts, trippy cartoons, tropical fruit imagery, or weed puns so bad they loop around to genius. (Dank & Furious, Rick and Mortree, Zaza’s Inferno, Bubblegum OG, the list goes on.)

Aversano began organizing the baggies like a museum archivist. By neighborhood. By color. By theme. The project, eventually titled “Ziploc City”, became an unintentional ethnography of New York’s unregulated weed economy.

“This wasn’t legal weed packaging,” he said. “None of this was coming from dispensaries. These are street-level products—bootleg brands, random strains, pop-culture mashups—sold hand-to-hand and tossed aside.”

In a way, the baggies tell a story that NYC’s political and cultural institutions haven’t caught up with yet. Weed may be legal now in New York, but the ecosystem around it is still chaotic, semi-regulated, and deeply shaped by its street-level past.

Weed Goes Graphic: The Rise of Underground Branding

What’s most striking about the baggies is the sheer effort put into their visual design.

“These things are miniature advertisements,” Aversano explains. “Even if they’re just selling two grams of flower, they’re competing with dozens of other dealers. Design matters.”

It’s true. As weed entered the mainstream, its aesthetic evolved. Gone are the days of dime bags and mystery strains. Today’s underground weed market mirrors the world of snacks, energy drinks, or candy. The goal? Catch your eye. Get shared. Go viral.

Some designs reference pop culture: Pokemon, Looney Tunes, anime, even luxury fashion logos. Others mimic food brands—bags spoofing Cheetos, Skittles, or Sour Patch Kids are common. There’s a strange irony in the overlap: branding once reserved for kids is now repurposed to move product in adult underground economies.

“There’s something kind of dystopian about it,” Aversano says. “It’s like a weird mirror of capitalism. Weed gets legalized, but the market that built it still survives—in more cartoonish packaging.”

Trash, Art, and the Grey Areas In Between

To many, these baggies are just litter—plastic waste blowing down a Brooklyn block. But to Aversano, they’re a reflection of the city’s contradictions: glamor and grime, legal and illegal, hyper-visibility and total discard.

“I never saw this as a weed project,” he says. “It’s about what we throw away. What ends up on the sidewalk says something about who we are.”

The photography series captures each bag against a flat, neutral background—no context, no location. Just the object, cleanly lit, isolated. The result feels almost like scientific documentation. But there’s playfulness, too. Some photos are grouped by theme (cartoons, colors, strain names). Others are presented like museum relics.

The images highlight absurdity and creativity at once. One bag reads: Purple Monkey Balls. Another features a holographic foil portrait of Tony the Tiger. Another has the “Supreme” logo repurposed for a strain called HighPreme OG.

The photos turn trash into taxonomy. They ask viewers to consider the world these baggies come from—and why we rarely pay attention to it.

A City Shaped by Legalization (and Loopholes)

New York legalized recreational marijuana in 2021. But rollout has been messy. Legal dispensaries took years to open, and enforcement of street sales remains inconsistent. As a result, the city exists in a weird limbo: weed is legal, but much of the buying and selling still happens in the shadows.

These baggies live in that limbo. They’re products of a market that’s thriving in plain sight, yet technically unregulated. For many New Yorkers, buying weed still means texting a number, meeting a delivery guy, and getting your product in a flashy little bag.

“This is what legalization looks like at street level,” says Aversano. “Not clean, Apple Store-style dispensaries—but bootleg branding, old habits, and lots of plastic waste.”

The irony? As the legal industry struggles to find its footing, the underground market has never been more visible—or more confident in its presentation.

Environmental Irony: Green That Isn’t Green

Beyond aesthetics and legality, there’s a more sobering layer: the environmental cost.

“These bags are everywhere,” Aversano says. “Parks, train platforms, sidewalks. They’re not biodegradable. They’re not recyclable. And no one’s talking about them.”

In a city already drowning in microplastics and waste, the weed boom has added another layer of disposable consumption. Each small bag is single-use, barely noticed, and tossed seconds after it’s emptied.

“Cannabis is supposed to be about wellness, nature, plant medicine,” he says. “But the packaging? It’s pure landfill. That contradiction is part of what I wanted to show.”

In some ways, the project functions like environmental journalism. Not overtly political, but undeniably revealing.

Reactions, Exhibits, and What’s Next

Since releasing some of the images online, the project has gained attention. Streetwear blogs. Art critics. Environmental circles. Even cannabis advocates.

Reactions range from fascination to discomfort.

“Some people say, ‘This is genius—nobody’s looked at this before,’” he says. “Others say, ‘Why glorify drug trash?’ But to me, that’s the whole point. It’s something you walk past every day and never think about. I just decided to look closer.”

A gallery exhibition is currently in the works, with prints organized like scientific displays. There are plans for a photo book. Maybe even a collaboration with a streetwear label—ironic, considering how many of the baggies rip off fashion logos.

But Aversano is clear: he’s not promoting weed. He’s not condemning it either. He’s documenting something real, something physical, and something most people overlook.

Impression

The “Ziploc City” project isn’t about drugs. It’s about design. About waste. About urban aesthetics. It’s about what we throw away—and what those objects say about our values, our habits, and our contradictions.

It’s also a reminder that even in the smallest pieces of trash, there are stories. Cultural shifts. Economic systems. Aesthetic trends. You just have to be willing to look closely.

As legalization reshapes how we see cannabis, Justin Aversano offers a sideways glance—a visual archive of a moment in transition. One baggie at a time.

Coming Soon:

“Ziploc City” exhibition and photo book

Follow Justin Aversano on Instagram [@justinaversano] for updates

No comments yet.