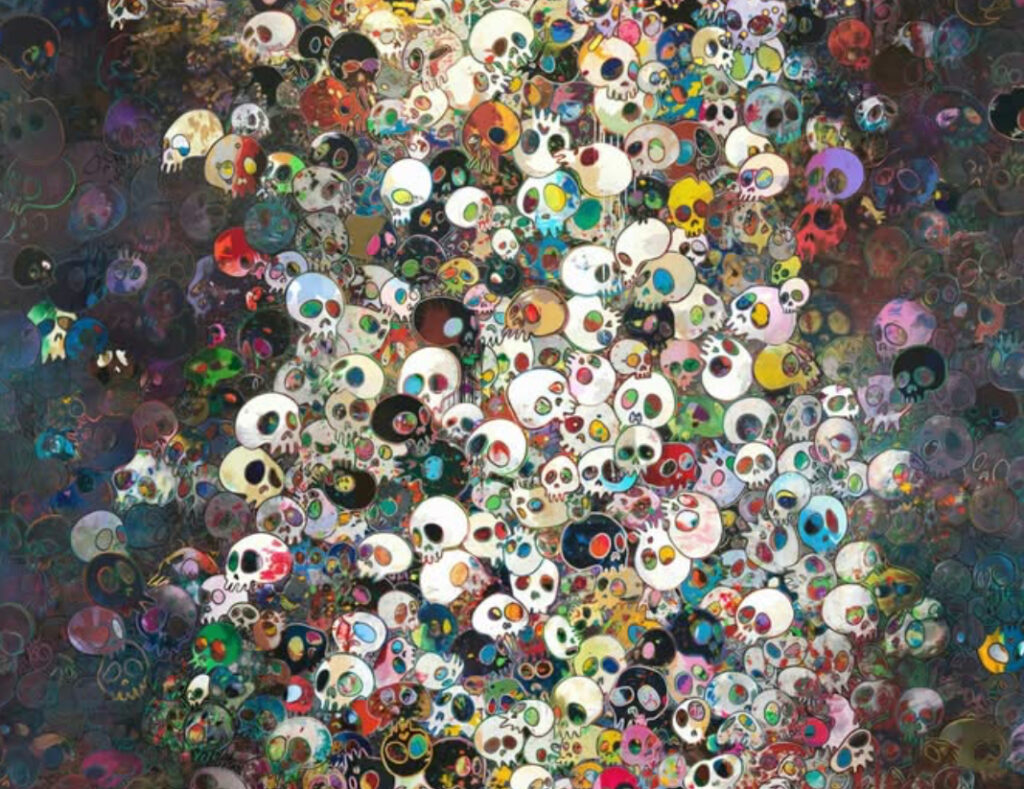

In the wake of national disaster, even the brightest colors curdle. Created in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and the ensuing Fukushima Daiichi nuclear meltdown, Takashi Murakami’s End of Line (2011) does not simply mark a pivotal moment in the artist’s career—it redefines the possibilities of his entire practice. Measuring 300.04 x 234.47 cm, the monumental work intentionally echoes the traditional Japanese byōbu (folding screen) format, yet its surface offers no pastoral idealism or festive courtly scenes. Instead, it is a site of entropy. Murakami, who once reigned supreme as the smiling czar of “Superflat,” here presents a catastrophic flattening of visual pleasure, a self-interrogation masquerading in his signature palette.

Surface Illusion: Technique as Tactical Deception

Though it deploys the same medium—acrylic on canvas mounted on board—that Murakami perfected for his commercial collaborations with Louis Vuitton, End of Line is a rejection of decorative clarity. Its meticulous surface mimics digital flatness, but the substance beneath is anything but synthetic. According to technical notes later shared by the Broad Art Foundation, Murakami incorporated trace Fukushima soil samples into his pigment mixture—a symbolic contamination that gives literal weight to the painting’s death drive.

Color Theory & Structural Layout

- Pinks and blues, standard in Murakami’s kawaii-era iconography, are rendered acidic, as if exposed to fallout

- Radioactive greens and yellows disrupt the harmony, pulsing like hazard indicators

- Skull and flower motifs spiral in a vortex, suggesting gravitational collapse rather than decorative rhythm

- Pixelation in certain regions simulates analog degradation and visual static—a nod to CCTV aesthetics used in Fukushima’s exclusion zones

The surface seduces, but like Warhol’s electric chairs, its sugar conceals violence.

Iconographic Autopsy: Murakami’s Broken Symbols

Murakami’s iconography is never static. He has repeatedly reshuffled the lexicon of his so-called Superflat world: smiling flowers, cartoon skulls, and the enigmatic DOB character. In End of Line, these familiar forms collapse into post-nuclear ruins, suggesting not only the end of an era, but perhaps of his own ability to sustain the illusion.

The Flowers Rot

The formerly cheerful blossoms now exhibit serrated petals and bruised coloration. Rendered with necrotic veining and misshapen symmetry, they evoke biological mutation. Critics have noted their arrangement echoes radioactive dispersion maps released during the Fukushima crisis—Murakami’s way of mapping invisible trauma onto visible tropes.

The Central Skull: A Hollow Sovereign

At the compositional core, a massive skull rendered with ukiyo-e perspective techniques seems to hover, or perhaps implode, into digital dissolution. Its sockets are vacant but pixelated, mimicking the void of DOB’s eyes in earlier works. The skull disintegrates into numerical code, alluding to death by data, by exposure, by virtual oblivion.

The Language of Meltdown

Textual fragments litter the background:

- Binary strings

- Fractured kanji radicals for “end” (終) and “electricity” (電)

- Glyphs resembling glitched QR codes

Together, these point toward Fukushima, but also the breakdown of language itself—a linguistic entropy accompanying ecological and cultural disaster.

Crisis and Context: Post-Superflat Realism

Murakami’s 2000 Superflat manifesto proposed a seamless visual continuum between fine art and consumer culture, otaku obsession and painterly tradition. End of Line detonates that theory from the inside. It doesn’t bridge “high” and “low”—it turns them into ashes.

Art Historical Touchpoints:

- Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster series—pop tropes reoriented toward tragedy

- Francis Bacon’s papal grotesqueries—institutional paralysis amidst divine horror

- Yoshitomo Nara’s weaponized innocence—another Japanese artist forced to turn childishness into critique

As art historian Hiroki Yamamoto writes in Post-Superflat: Japanese Art After Cuteness (2020):

“Murakami here conducts a cultural vivisection. These are not references. They are remains.”

Exhibition History and Institutional Canonization

End of Line debuted in 2012 at Blum & Poe Los Angeles, drawing polarized reaction. Artforum called it “an apocalyptic triumph of visual sincerity,” while Tokyo Art Beat dismissed it as “nuclear kitsch masquerading as catharsis.”

By 2015, the Broad Art Foundation acquired the piece for a then-undisclosed sum (estimated between $4M and $5M), placing it in strategic dialogue with:

- Jeff Koons’ Tulips (1995–2004)

- Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors

Murakami’s apocalypse now resides among capitalist allegories and infinite obliteration—fitting companions for a work so conceptually terminal.

Today, the Broad displays the work on semi-permanent rotation, with advance-viewing appointments required due to the painting’s unsettling psychic effect, particularly on younger audiences. Staff have reported instances of viewers physically turning away—evidence that its pop façade fails to fully neutralize its existential core.

Post-Fukushima Art: Radiation and Reverberation

Japan’s post-2011 art world has largely been defined by aesthetic responses to the invisible crisis—radiation, displacement, and institutional failure. Murakami’s End of Line is neither protest nor elegy. It is forensic documentation, using the tools of commercial spectacle to conduct an autopsy on optimism.

Noteworthy components include:

- Radial layouts mirroring dispersion diagrams from Japan’s Meteorological Agency

- Streaks of acid yellow digitally mimic Geiger counter readouts

- Pentimenti revealed through infrared scanning show erased smiley faces, suggesting internal conflict in the composition process

Murakami himself said in a 2013 interview:

“After the tsunami, cuteness became impossible. This painting is my farewell to innocence.”

Legacy: The Death of the “Happy Factory”

Murakami’s early 2000s collaborations with Louis Vuitton, and his founding of Kaikai Kiki Co., projected him as a kind of cultural entrepreneur—a Warhol for the digital age. End of Line obliterates this persona.

From this point onward, his works became darker, meditative, and mournful:

- The 500 Arhats (2012) responded directly to 3/11, commissioned by the Qatar Museums Authority

- Arhat Cycle expanded Buddhist themes into post-human territory

- His animated music video for Billie Eilish’s “you should see me in a crown” (2019) draws clear visual DNA from End of Line’s digital nihilism

According to scholar Midori Yoshimoto:

“This is the moment when Murakami ceases to be an entertainer. He becomes a witness.”

Current Relevance and Future Readings

In an era dominated by AI-generated art and endless simulation, End of Line remains fiercely analog. It is painted, labored, scarred. Despite its digital sheen, it resists obsolescence. Indeed, it becomes more prescient by the year.

Recent interest in climate-focused curatorial frameworks has reinvigorated its resonance. Exhibitions across Europe and Asia increasingly reference End of Line in relation to anthropocene aesthetics, eco-trauma, and nuclear semiotics.

Meanwhile, market valuation continues to climb. A 2023 Christie’s appraisal placed it between $18–$22 million, with institutional loans lined up through 2026.

Impression

End of Line is not a conclusion in the narrative sense—it is an alarm, a rupture. It takes the language of cuteness and crushes it under radioactive symbolism. It does what Murakami’s early Superflat works did not dare: confronts Japan’s cultural complicity in its own disassociation.

Recommended Scholarship & Resources

- Murakami’s Apocalypse: End of Line and the Fukushima Sublime (MIT Press, 2018)

- Post-Superflat: Japanese Art After Cuteness (Thames & Hudson, 2020)

- Artforum, “Smile No More: Murakami’s Blackout” (May 2012)

- The Broad’s internal Acquisition Notes (2015, unpublished)

No comments yet.