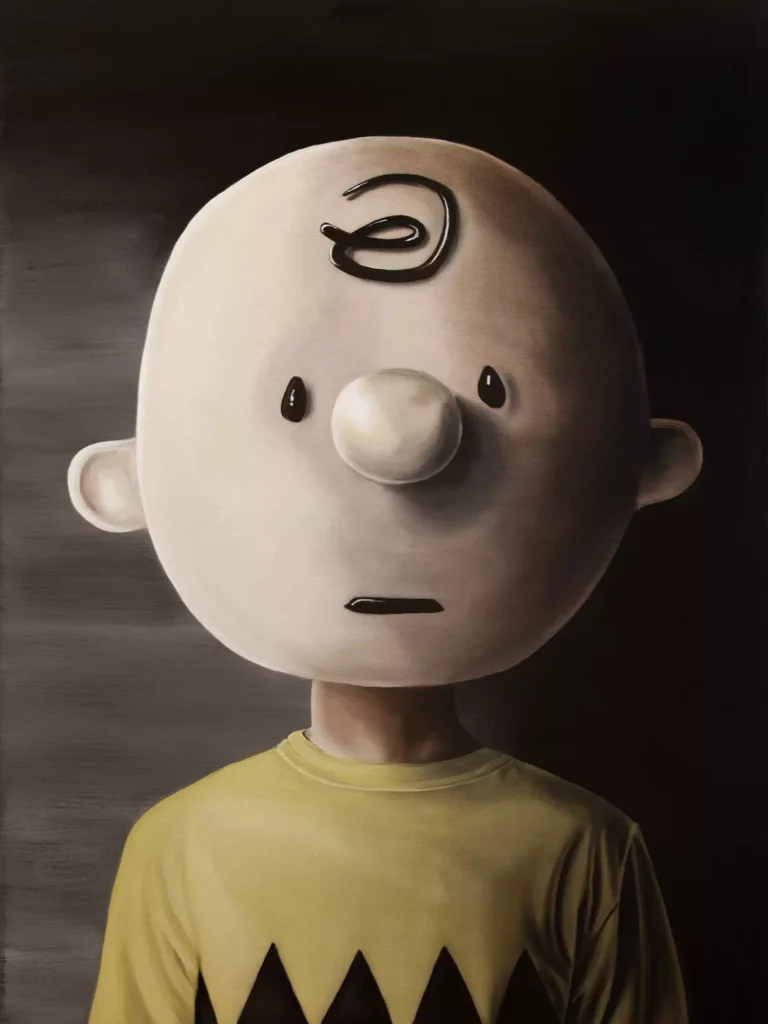

Gregory Malphurs’ Mask No. 17 takes one of the most recognizable faces in American culture — Charlie Brown from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts — and transforms it into something quietly devastating. The child whose round head once symbolized innocence, awkwardness, and optimism is here reimagined as an empty vessel. The painting depicts a boy wearing a rigid, oversized mask with a spiral of hair on his forehead, teardrop-shaped eyes, and a stiff-lipped expression. The yellow zigzag shirt leaves no doubt about the reference, yet everything familiar feels wrong. It’s as if Charlie Brown has been embalmed in melancholy.

the deconstruction of an icon

In Mask No. 17, Malphurs engages directly with the mythology of Peanuts, but he strips away the comic’s gentle humor. Schulz’s Charlie Brown was the every child — endlessly defeated but never embittered, always returning to the pitcher’s mound or the kite string. Malphurs’ figure, however, has stopped trying. The cartoon’s expressive motion has been replaced by stillness. The smile is gone, the line-work hardened into sculpture, and the background fades into an ashen void.

Where Schulz gave us empathy, Malphurs offers emptiness. The painting becomes less about the boy and more about what remains when hope itself calcifies. By turning a beloved cartoon into a haunting effigy, Malphurs asks what happens when nostalgia stops comforting us and starts confronting us.

the mask as allegory

The title, Mask No. 17, invites interpretation. It suggests a series — an ongoing study of identity, artifice, and emotional disguise. The face in the painting is literally a mask, smooth and opaque like porcelain, concealing whatever lies beneath. Malphurs’ technique heightens this sense of artificiality: the sheen on the forehead, the hyperreal backdrops along the jaw, and the absence of visible brushstrokes make the surface eerily synthetic.

But the subtle detail of the exposed neck — rendered in warm, lifelike tones — betrays the human trapped beneath. It’s a visual contradiction: the mask suggests protection or conjure, yet here it suffocates. This tension becomes central to the work’s emotional charge. The viewer senses the presence of a real person hidden behind a cultural icon, as if Malphurs is painting the burden of representation itself.

between pop and pathos

Artists have long used cartoon characters to probe the boundaries between pop and psychology — from KAWS, who inflates and dissects beloved figures like Mickey Mouse and the Simpsons, to Yoshitomo Nara, whose sad-eyed children merge innocence with menace. Malphurs shares their visual literacy but diverges in tone. He avoids irony. His Mask series doesn’t parody pop culture; it mourns it.

Where KAWS’s figures are slick symbols of branding and consumption, Malphurs’ are quiet studies in despair. His Charlie Brown doesn’t wink or cross his arms — he simply stares, hollow-eyed, into the viewer’s discomfort. The painting transforms a cultural emblem into a psychological portrait, balancing on the edge between humanity and hollow iconography.

By choosing Charlie Brown, Malphurs touches something deeper in American consciousness. This is the child who embodied optimism in defeat — the one who never kicked the football, never won the game, never got the girl, but never stopped trying. In Malphurs’ reimagining, that persistence has curdled. The optimism of the mid-century American dream has cracked under the pressure of contemporary fatigue.

nostalgia as disquiet

There is something deeply American about Charlie Brown’s sadness — the belief that failure can be redeemed through effort. In Mask No. 17, that faith has dissolved. The yellow shirt still radiates its familiar warmth, but the head above it is a marble-gray void. Malphurs paints nostalgia as a form of mourning: we recognize the icon, but we can no longer reach the innocence it represents.

This is where Mask No. 17 transcends pop art. Instead of celebrating reproduction or cultural memory, it exposes their emotional cost. Malphurs reveals nostalgia as a trap — a loop of recognition without renewal. We see Charlie Brown, but we do not feel him. The connection between viewer and character has grown cold, mediated by decades of cultural recycling.

the uncanny and the sacred

There’s a strange reverence in Malphurs’ handling of light. The figure is illuminated like a saint in a Renaissance painting, emerging from a background that fades into black. The chiaroscuro effect gives the subject a near-religious aura, yet what we witness is not transcendence but entrapment. The mask becomes a relic, the symbol of a faith long abandoned.

In this sense, Mask No. 17 functions like an icon painting of modern alienation. It worships the image while simultaneously mourning its loss of meaning. The familiar curl of hair atop the head — once a symbol of comic simplicity — becomes a glyph of endless repetition, a spiral that traps both artist and audience within the orbit of memory.

the emotional architecture

Malphurs’ composition is deceptively simple. The centered figure, straight shoulders, and subdued palette suggest portraiture, but the formal calm hides deep anxiety. The contrast between the living neck and the lifeless mask introduces a subtle violence. It’s as if the boy has become the mannequin version of himself — a transformation from subject to object, from person to brand.

The emptiness of the eyes — glossy and black — denies reflection. They absorb light without giving it back, a visual metaphor for depression or emotional burnout. The mouth, rendered as a flat curve, reads not as sadness but as resignation. The work’s power lies in its restraint: Malphurs captures despair without drama, stillness without peace.

the culture

The Peanuts comic strip debuted in 1950, a time when America sought simplicity and optimism in the aftermath of war. Schulz’s characters embodied the anxieties of ordinary life but softened them through humor. Charlie Brown’s failures were intimate, universal, and safe.

Seventy-five years later, in an era of digital overload and cultural fatigue, Malphurs revisits that symbol and finds only emptiness. His painting speaks to a generation for whom the old promises of optimism feel obsolete. The image of Charlie Brown becomes a mirror of cultural exhaustion — a reminder that even our nostalgia has grown tired.

By isolating the character in darkness, Malphurs denies the communal warmth of the Peanuts world. There is no Lucy to tease him, no Linus with his blanket, no Snoopy dancing on top of the doghouse. The silence is total. What remains is the icon alone with his mask — an emblem of all the ways America hides behind its own myths.

impression

Mask No. 17 is not a portrait of Charlie Brown; it is a portrait of what Charlie Brown has come to mean. Gregory Malphurs transforms Schulz’s innocent protagonist into a figure of existential paralysis — a symbol for a generation that has outlived its optimism.

Through masterful technique and profound restraint, Malphurs renders the cultural mask as both armor and prison. In doing so, he reveals the fragility of the identities we inherit from media, childhood, and nostalgia.

The painting lingers because it doesn’t mock or celebrate its subject — it laments it. Charlie Brown has finally stopped running toward the football. He stands still, facing us, asking what’s left when the story ends and the laughter fades.

No comments yet.