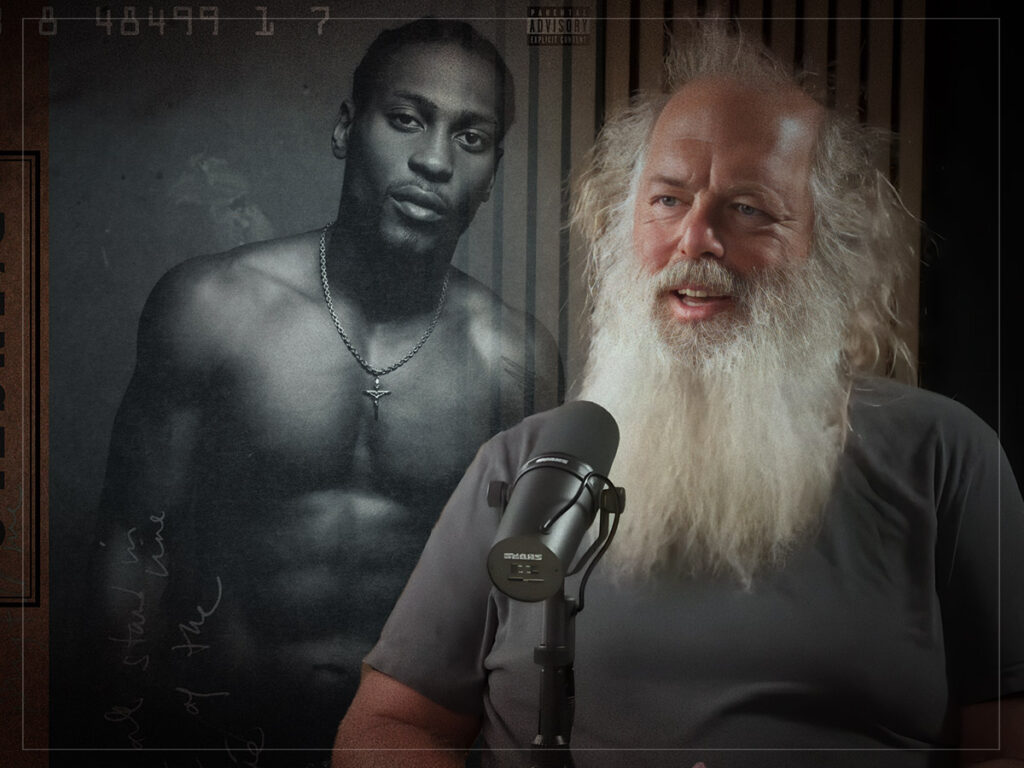

When Rick Rubin says something is “absolutely perfect,” you pause.

Perfection, for Rubin, has nothing to do with flawlessness. It’s about vibration — that rare alignment between intention, craft, and spirit. And when Questlove, sitting across from him on Broken Record, mentioned Voodoo, Rubin didn’t hesitate. D’Angelo’s 2000 masterpiece, he said, was that alignment.

Rubin’s words echoed a truth long felt by musicians and fans alike: Voodoo wasn’t just an album. It was a pulse. A séance. A record that refused to sit still — because it was never about being frozen in time. It was about being alive.

style

To understand Voodoo, you have to imagine a humid room inside Electric Lady Studios in New York, 1998.

Questlove’s drums hang just behind the beat. Pino Palladino’s bass hums like a conversation below language. D’Angelo, shirt loose, head bowed, is sketching vocal harmonies that don’t sound written so much as breathed into existence.

This wasn’t a record produced. It was conjured.

The Soulquarians — that rare cross-section of musicians, thinkers, and misfits — orbited each other inside those walls. The studio became an ecosystem: Erykah Badu floating through one week, Mos Def the next, Q-Tip stopping by with a vinyl crate. Everything leaked into everything else. In this open architecture of creation, D’Angelo built Voodoo, brick by groove.

The sessions could last twelve, fourteen hours. There was no deadline, no executive tapping a wristwatch. D’Angelo was chasing feel — that elusive tension between looseness and control, the gospel that slips through quantized grids. Questlove once said they intentionally “played wrong” — snare just behind, bass slightly before — to recreate the swing of imperfection. On paper it shouldn’t have worked. On tape it felt like truth.

the rhythm that broke time

Listen to Voodoo today and it still breathes differently from every other record in its era.

There’s something slanted, human, elastic in its rhythm. “Playa Playa” opens with a throb that never quite resolves. “Chicken Grease” slides across the floor, D’Angelo’s falsetto slicing through with preacher’s confidence and sly humor. Even “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” — now mythologized as both sensual anthem and artistic albatross — stretches time until it feels suspended between heartbeat and breath.

What Rick Rubin recognized as perfection wasn’t cleanliness. It was coherence: a sonic world so self-consistent that any note outside it would collapse the structure. You can’t remix Voodoo; its DNA resists manipulation.

Every shaker, every inhale, every blurred hi-hat is part of the organism.

This was also where D’Angelo’s reverence for his ancestors came through. Voodoo wasn’t retro; it was ancestral. The lineage of Sly Stone, Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, Prince, and Fela Kuti vibrates through every measure — but filtered through hip-hop’s fragmentary sensibility. You hear Dilla’s fingerprints in the drum swing, the ghost in the machine that makes Questlove’s live drums sound sampled. You hear gospel’s call and response in D’Angelo’s own overdubbed choirs, voices that seem to orbit him like spirits.

It’s as if Voodoo turned black musical history into muscle memory.

sex, spirit, and solitude

Lyrically, Voodoo moves in two registers: the sacred and the carnal.

D’Angelo’s genius was making them inseparable. On “The Line,” he sounds like he’s singing through fire and faith: a soldier for love and integrity. On “One Mo’Gin,” nostalgia curls into eroticism; memory becomes touch. “Devil’s Pie” chastises greed and excess with the gravity of a preacher who’s seen too much sin, yet it thumps with the seductive menace of temptation itself.

The entire album wavers between bedroom and altar. The way he sings “How does it feel?” is not just lust — it’s confession, surrender, proof of existence. It’s soul stripped of sermon, faith stripped of certainty.

And yet, for all its intimacy, Voodoo is also profoundly lonely. Beneath the lush layering lies an artist drifting further inward, wary of stardom, increasingly protective of his private universe. The record feels like someone barricading the studio door — letting light in only through slivers. You sense D’Angelo already bracing against the glare that would follow.

the body as myth

The myth of Voodoo is inseparable from its visuals. The video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” changed everything.

A single take. A single torso. D’Angelo, bare-chested, glistening, gazing into the lens not as performer but as offering. The camera moves as if through worship — slow, deliberate, reverent.

What was meant as an expression of vulnerability became a trap.

The world froze him into that image, turning an introspective craftsman into a sex symbol. Audiences screamed, critics swooned, but D’Angelo disappeared. The man who’d just made the most intimate, spiritually charged record of the decade vanished into self-imposed silence.

That disappearance only magnified Voodoo’s aura. It wasn’t just an album anymore; it became a relic. A gospel written in smoke.

the alchemy of the soulquarians

The story of Voodoo is also the story of a collective chemistry that will likely never be replicated.

The Soulquarians — named for their shared Aquarius birthdays — were a constellation of restless black artists refusing categorization. Their sonic palette expanded across hip-hop, R&B, and jazz, but also funk, afrobeat, and spiritual minimalism. Their process was jam as religion.

Questlove kept time but also disrupted it. James Poyser floated harmonies through Wurlitzers and Rhodes pianos. Roy Hargrove’s trumpet carved air pockets through the density.

And in the corner, D’Angelo layered vocals like sacred architecture — hushed, polyphonic, deliberate.

This was a rebellion not through volume, but through patience.

At a time when R&B was leaning glossy and quantized, Voodoo insisted on the human. Its imperfections became its politics. It wasn’t chasing radio; it was chasing resonance.

Rick Rubin, ever the spiritual minimalist, understood that language. His declaration of perfection wasn’t about the charts or sonic fidelity — it was about intention made audible. Voodoo is an album that achieves exactly what it set out to do, without compromise or apology.

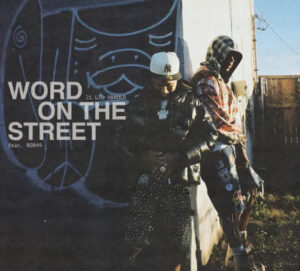

the world responds

When Voodoo dropped on January 25, 2000, the response was both immediate and gradual.

Commercially, it debuted at No. 1 on Billboard, selling over 300,000 copies in its first week. Critics wrote in reverent tones. Time magazine named it Album of the Year. Spin, NME, The Source, Rolling Stone — all recognized its gravity, even if not all fully understood it yet.

But the deeper resonance came later. As neo-soul faded as a marketing term and hip-hop accelerated into its shiny millennium phase, Voodoo remained stubbornly analog, defiantly tactile. Producers and musicians would study its grooves for years.

Frank Ocean, Kendrick Lamar, Erykah Badu, Anderson .Paak, H.E.R., and countless others have cited it as compass or scripture.

It wasn’t just about sound — it was about permission. Voodoo gave black artists space to be weird, slow, complicated, spiritual, unguarded. It said you could stretch, stumble, let silence talk.

View this post on Instagram

Rubin’s Mirror

Rick Rubin’s career — from Licensed to Ill to Blood Sugar Sex Magik to Yeezus to American Recordings — has always orbited the same principle: purity of feeling over perfection of form.

So when he calls Voodoo “absolutely perfect,” he’s naming kinship. He’s recognizing an artist who chased essence until nothing extraneous remained.

For Rubin, perfection isn’t sterile. It’s when every sound, every flaw, every breath coheres into something inevitable. Voodoo achieves that. It’s not pristine; it’s complete. The record doesn’t need editing or remastering — it needs listening, repeatedly, until you find your own pulse inside it.

There’s also something profoundly spiritual about Rubin’s choice of words.

To call an album perfect is to acknowledge its transcendence — that it exists beyond critique, in that rare space where art feels not made but discovered.

Voodoo feels discovered. It’s less an album than an excavation of a timeless groove waiting underground.

time and absence

Perfection has its cost.

In the years after Voodoo, D’Angelo withdrew. The fame felt corrosive. The image overshadowed the art. He struggled — publicly and privately — with identity, expectation, and addiction.

For over a decade, silence filled the space where Voodoo had reverberated.

Yet that absence deepened the myth. When he reemerged in 2014 with Black Messiah, the continuity was striking — the same molten grooves, the same spiritual undertones — but also a new urgency, a political fire sharpened by years in the wilderness.

You realized then that Voodoo wasn’t just a moment. It was a seed still unfolding.

the long arc of influence

Twenty-five years on, Voodoo remains a reference point for musicians obsessed with feel.

Studio engineers still talk about its “drunken time.” Bassists still study Pino’s tone. Drummers still chase the impossible swing of Questlove’s snare. Vocalists still marvel at D’Angelo’s stacked harmonies, where ten whispers create a choir.

But maybe its most lasting impact lies outside of technicalities.

Voodoo restored mystique to black artistry at a time when overexposure was becoming the norm. It proved that patience could be radical, that groove could be intellectual, that sensuality could be sacred. It gave permission to be still, to build worlds from breath and silence.

For listeners, it remains a private space — headphones on, eyes closed, body swaying slightly out of sync. You don’t just hear Voodoo; you enter it.

circling the circumference

When Questlove revisited Voodoo on Broken Record, two decades removed, he seemed both proud and haunted. He talked about the countless takes, the exhaustion, the late-night philosophical debates about what funk really is. And then Rubin said it — “That record is absolutely perfect.”

You can almost hear Questlove exhale.

For years, he’d called Voodoo the hardest thing he’d ever worked on. The slowest. The most painful. The most beautiful. For Rubin — the zen producer who finds holiness in minimalism — to affirm that struggle as perfection felt like closure.

But more than that, it reframed the entire project. It wasn’t just about musicianship. It was about faith — in the process, in the sound, in the silence between beats.

Rubin’s compliment wasn’t just for D’Angelo; it was for everyone who believes in listening harder, longer, deeper.

what “perfect” really means

Voodoo endures not because it’s untouchable but because it touches everything: jazz, gospel, funk, hip-hop, blues, and whatever language the soul invents to survive.

It refuses time, refuses categorization, refuses even its own success. It is, paradoxically, both human and divine — a record that bleeds but never breaks.

Perfection, in this sense, isn’t about flawlessness. It’s about completion — the sense that nothing is missing, that every imperfection is exactly where it should be.

In Voodoo, silence has weight, time has elasticity, groove has divinity. It’s not an album you finish; it’s one you return to for calibration — to remember what it feels like when black music breathes without apology.

View this post on Instagram

still in the room

Maybe that’s why Voodoo still feels alive in 2025.

Because it’s not nostalgic — it’s present tense. It hums in the same key as breath, as heartbeat, as the pause between memory and motion. You can drop the needle anywhere — “Spanish Joint,” “The Root,” “Africa” — and the room reconstitutes itself: smoke curling, snare lagging, D’Angelo’s voice both near and unreachable.

Perfection isn’t the absence of error.

It’s when you stop needing to correct anything.

So yes, Rick Rubin was right.

Voodoo is absolutely perfect — not because it sounds right, but because it feels inevitable.

Because two and a half decades later, we’re still inside it. Listening. Learning. Letting it move.

No comments yet.