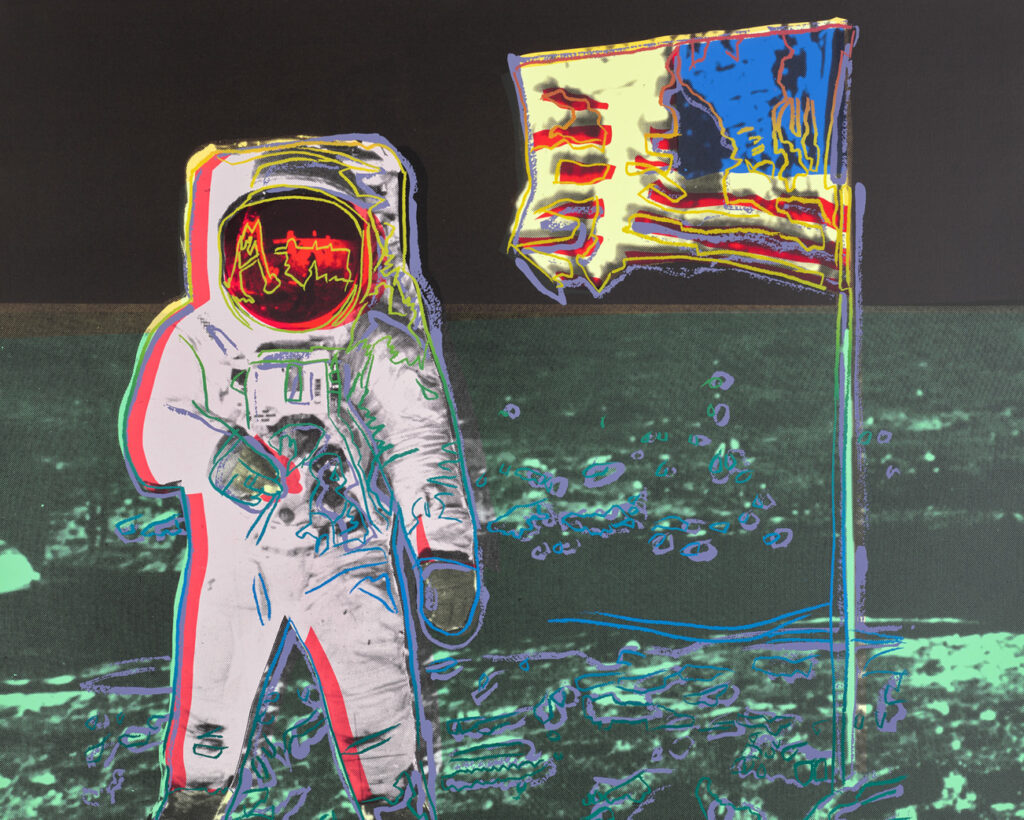

In 1987, Andy Warhol turned his silkscreen gaze skyward. Moonwalk — a vibrant, hallucinatory depiction of an astronaut standing beside the American flag on the lunar surface — was among the last works he completed before his sudden death that February. It is, in many ways, Warhol’s farewell statement: a cosmic reflection on fame, spectacle, and the mythmaking machinery of modern America. The piece reinterprets one of the most iconic photographs of the 20th century — Buzz Aldrin on the Moon, 1969 — and transforms it into something both familiar and perhaps outside from some mundane circumference.

Rendered through fluorescent outlines and electric distortions, Moonwalk exemplifies Warhol’s ability to turn history into image, and image into cultural mythology. In his hands, the moment of human transcendence — the first step on another world — becomes another screenprint, a mass-produced emblem of aspiration, nationalism, and illusion.

warhol and the american dream

From Campbell’s soup cans to Marilyn Monroe, Andy Warhol spent his career redefining what it meant to be American. He took the products and faces of consumer culture — disposable, glossy, omnipresent — and elevated them to art. By the 1980s, the artist had already dissected nearly every symbol of the American Dream. With Moonwalk, he turned to the last frontier: outer space.

The Apollo 11 landing was not just a scientific achievement; it was a spectacle of American power. Broadcast live to over 600 million viewers, Warhol understood television better than any artist of his generation. His fascination with the screen, the mediated image, and celebrity as performance converged perfectly with this historical moment. In Moonwalk, the astronaut — whose face is hidden behind a reflective visor — becomes an anonymous hero, a stand-in for the collective imagination. The figure could be anyone. The Moon, too, becomes a stage.

Warhol’s reinterpretation strips the moment of realism and replaces it with hyper-color abstraction. The cool greens of the lunar surface clash with the saturated reds and yellows of the flag. The suit’s lines are traced in electric pink and turquoise. Everything vibrates. The composition is simultaneously patriotic and psychedelic — a cosmic pop dream viewed through the lens of 1980s neon culture.

image, myth, and media

Warhol’s Moonwalk was conceived as part of a larger series on American icons, commissioned by the art publisher Ronald Feldman. The project was meant to include multiple images reflecting milestones in U.S. history — from Martin Luther King Jr. to the moon landing — but Warhol’s death left only two Moonwalk prints completed. In many ways, this incomplete series mirrors the artist’s career-long preoccupation with repetition and incompletion.

The image itself was sourced from NASA’s public archives, part of the visual vocabulary of post-war America. Warhol, who had long blurred the line between advertising and art, saw NASA imagery as another form of branding — clean, heroic, and endlessly reproducible. By transforming it into a silkscreen, he pushed it further into the realm of simulacra.

The reflective helmet of the astronaut is particularly telling. Within its darkened dome, Warhol added faint red outlines of camera equipment and studio-like structures.

color and technique

Technically, Moonwalk is a masterclass in late Warhol silkscreen technique. The print’s base image is rendered in monochrome gray, while vibrant neon line-work outlines the astronaut and flag. The layering of colors — from cyan and magenta to lemon yellow — creates an almost holographic effect, as if the subject exists in multiple dimensions at once.

Warhol had long used misregistration, color bleed, and contrast as expressive tools. In Moonwalk, these effects mimic static and distortion — evoking a televised transmission rather than a pristine photograph. The result is a deliberate imperfection that heightens the sense of artificiality. It is a reminder that this historic event was experienced not through presence, but through screens.

The artist’s use of fluorescence, meanwhile, aligns with 1980s aesthetics, echoing the era’s fascination with technology, futurism, and consumer spectacle. Yet beneath the pop exuberance lies a melancholic undertone. The Moon, for all its glow, is empty. The astronaut, though triumphant, stands alone.

the american sublime

Throughout his career, Warhol returned to the theme of the sublime — not the romantic landscapes of nature beloved by 19th-century painters, but the sublime of media and machinery. The Apollo landing represented a new kind of awe: technological transcendence. By reinterpreting it as Pop Art, Warhol translated the sublime into the language of reproduction.

In this sense, Moonwalk is both celebration and critique. It celebrates human ambition, the desire to reach beyond our world, yet it also critiques the way such ambition becomes spectacle. The glowing flag, distorted and abstract, waves not in the vacuum of space but in the current of media saturation.

The Moon landing, in Warhol’s hands, is not a spiritual event but a broadcast — a screenprint of a screenprint. His astronaut is a figure of faith in technology, but also a ghost of modernity, caught in the eternal feedback loop of fame and image.

hum

Since its creation, Moonwalk has become one of Warhol’s most sought-after late works. The series was published posthumously by Ronald Feldman Fine Arts and Edition Schellmann in an edition of 160, with 31 artist’s proofs and several trial variations. It now occupies a special place in Warhol’s legacy: the intersection of pop culture, national myth, and cosmic imagination.

Museums and collectors alike regard Moonwalk as a summation of Warhol’s worldview. It encapsulates his obsessions — celebrity, repetition, media, color — and pushes them into the domain of the infinite. In its surreal glow, the boundaries between art and history dissolve.

As an artifact of the late Cold War era, the piece also captures a particular American sentiment: optimism tinged with uncertainty. The nation had conquered the Moon, yet was losing faith in its own mythologies. Warhol’s Moonwalksuspends this tension between achievement and illusion, between pride and parody.

No comments yet.