The story of the communist icon favored by the fashion world

how an icon survives

Icons don’t always survive by staying true to themselves—they endure by transforming. Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, and author who helped lead the Cuban Revolution alongside Fidel Castro, became one of the twentieth century’s most reproduced faces. His role in the revolution, his travels across Latin America, his tenure as Cuba’s Minister of Industries, and his death at the hands of CIA-backed Bolivian forces all belong to history. But the image—the beret, the beard, the stare—belongs to culture.

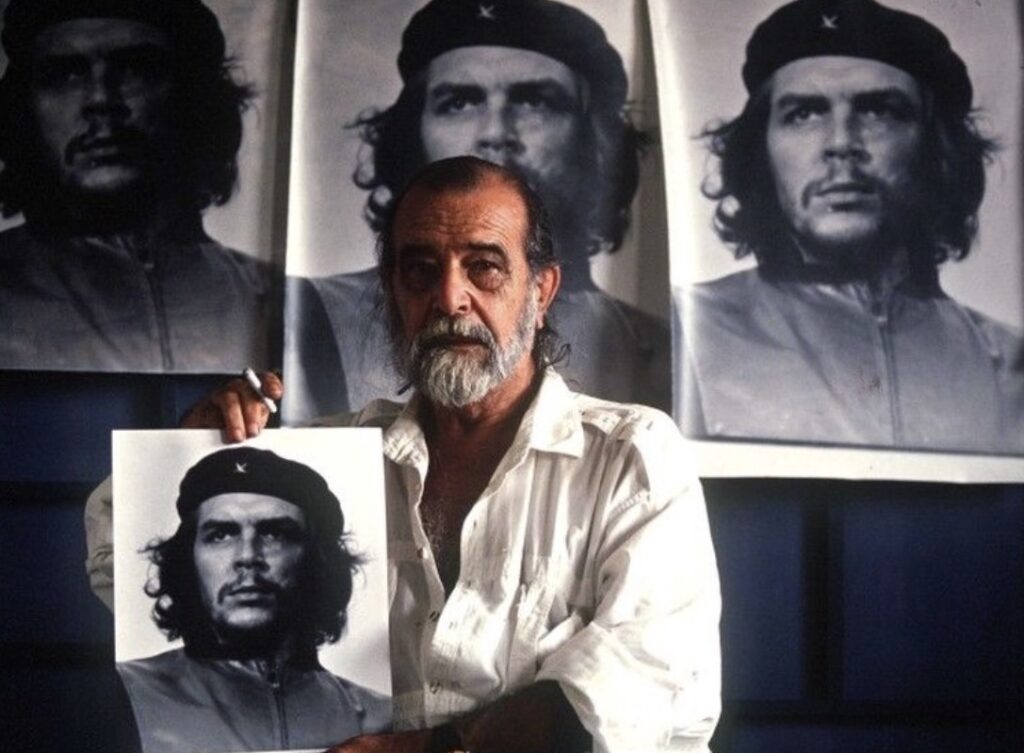

That transformation began with a single photograph. In March 1960, Cuban photographer Alberto Korda captured Guevara during a funeral for victims of a ship explosion in Havana. The image, later titled Guerrillero Heroico, froze Che’s defiant expression against an austere sky. It wasn’t published in Cuba at first, deemed too somber, but Korda gifted copies to visiting French intellectuals Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. By the time Paris Match printed it in 1967, just as news of Che’s death spread, the image had already begun its slow migration from history to mythology.

martyr or icon

After his execution, Guevara’s face began a second life—one detached from ideology. Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, who had briefly met Che as a teenager, produced a high-contrast silkscreen version on a red field in 1968. He distributed it freely at student rallies and rock concerts. Within months, it was everywhere—spray-painted on Parisian walls during the 1968 riots, stamped on posters, and worn on T-shirts at anti-Vietnam protests.

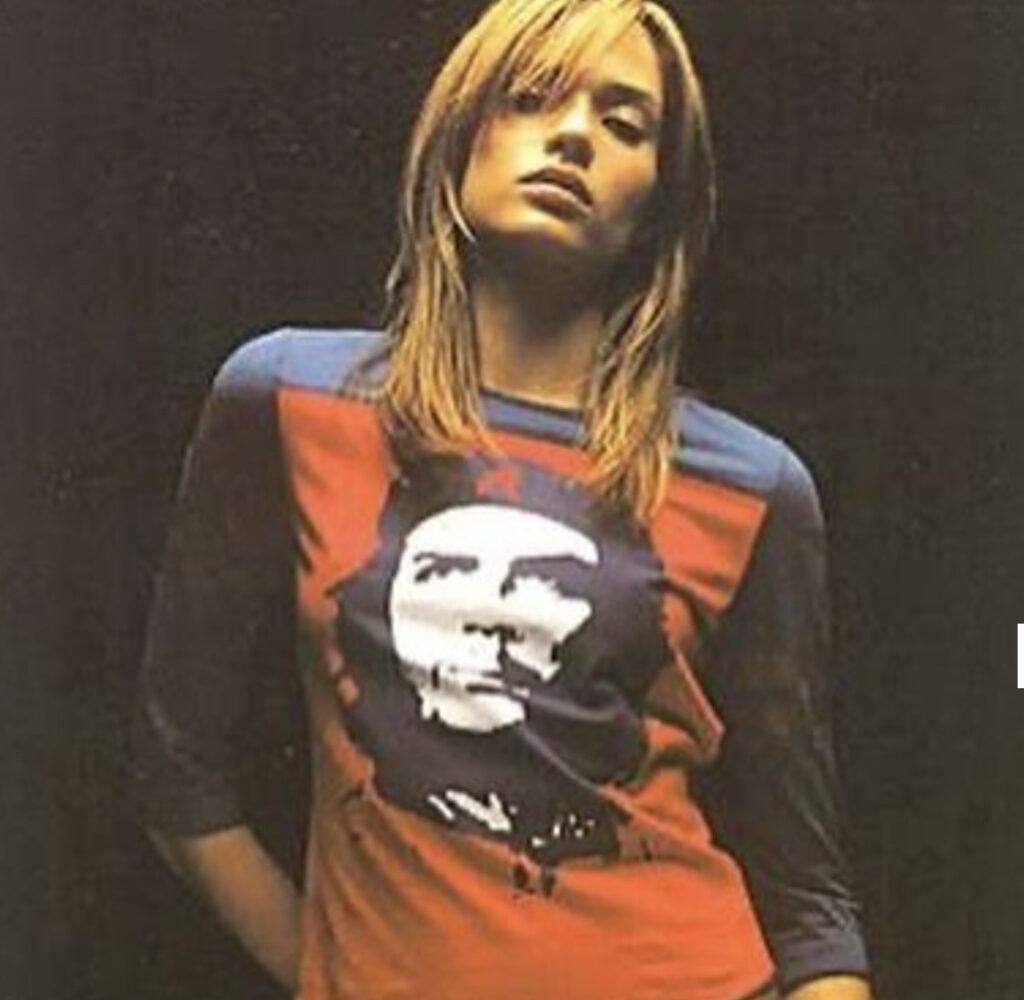

By the early 1970s, the Guerrillero Heroico had crossed into pop culture’s bloodstream. Print shops from Berkeley to London sold thousands of shirts for a few dollars each. Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd toyed with the image as irony. Punk zines reclaimed it as rebellion chic. The symbol of Marxist struggle became, paradoxically, the emblem of post-industrial consumer youth.

Korda himself, a loyal revolutionary, refused to commercialize the image. He saw it as belonging to the people, not the market. Yet in 2000, when Smirnoff vodka used Che’s likeness to sell alcohol, Korda sued—and won. He donated the settlement to Cuban hospitals, preserving the moral edge of his creation even as it became a global commodity.

capitalizing on anti-capitalism

By the 2000s, the irony had become impossible to ignore. The 2004 documentary Chevolution estimated that more than two billion reproductions of Che’s image had circulated by 2008. Rappers, actors, and fashion icons adopted him as shorthand for “defiance.” Jay-Z referenced him in Public Service Announcement; Johnny Depp and Prince Harry wore his shirts; designer boutiques sold baby onesies printed with his face.

As the myth metastasized, reinterpretations followed. Cuban exiles reminded the world of Guevara’s brutality at La Cabaña prison; left-wing historians defended him as a symbol of internationalist hope. His daughter, Aleida Guevara, argued that the ubiquity of his portrait still inspired resistance against conformity—a small victory in a world where capitalism sells rebellion back to itself.

Satire joined in: The Onion mocked the phenomenon with a T-shirt of Che wearing his own image. The Scottish Tartan Army once replaced his face with poet Robert Burns on charity shirts. Even Shepard Fairey’s Obey Giant campaign riffed on the aesthetic lineage, replacing Che’s stare with Andre the Giant’s.

Today, with thousands of Che items listed on eBay, his portrait may be capitalism’s purest paradox—proof that dissent, too, can be monetized.

the fashion revolution

Fashion, ever hungry for icons, embraced Che with equal parts fascination and irony. Jean Paul Gaultier was among the first to appropriate the revolutionary. In his 1999 sunglasses campaign, a surreal Fred Langlais illustration paired Guevara with Frida Kahlo. At his spring 1998 show, a model appeared on the runway in olive tones and a black beret—a clear homage to the guerrilla hero.

Then came the unforgettable moment of 2002: at São Paulo Fashion Week, supermodel Gisele Bündchen opened Cia.Marítima’s show wearing a bikini covered in Che prints. The gesture provoked both applause and outrage. Two years later, Elizabeth Hurley danced through London’s China White nightclub with a custom $4,500 Louis Vuitton Speedy bag embroidered with Che’s face—luxury meeting revolution in absurd harmony.

Streetwear was not far behind. Stüssy and Fuct printed Guevara’s likeness on hoodies and tees. Belstaff launched a “Trialmaster Che Guevara Replica Jacket,” mirroring the olive model from his 1952 motorcycle travels. Converse released Guerrillero Heroico-adorned Chuck Taylors in 2006, reissued again four years later.

But the most extravagant reinterpretation came from Chanel. In 2016, Karl Lagerfeld staged the brand’s Cruise show in Havana—a $12 million spectacle complete with vintage cars and cobblestone runways. Models wore crystal-studded berets and military-style jackets, their silhouettes nodding to Guevara’s uniform. Critics called it romantic revisionism; Cuban-American exiles called it offensive glamorization. Yet in the world of luxury, subversion sells.

In 2021, Supreme released a black nylon football jersey featuring Che’s portrait. It sold out in minutes—a symbol reduced to scarcity, authenticity measured by resale price.

from rebellion to relic

Che Guevara’s image has lived many lives: martyr, slogan, commodity, style. Each reinvention moves it further from the man himself and closer to the abstraction of cool. The irony is exquisite—his face, once the emblem of anti-capitalism, now graces the very markets he sought to dismantle.

In the West, memory of Guevara’s historical context has dimmed. The moral clarity of 1950s revolution does not translate to the algorithms of 2025. What remains is not the ideology but the outline—the aesthetic of defiance.

Perhaps that is how icons die: not by erasure, but by endless reproduction.

Maybe, at last, it’s time to let Che rest.

No comments yet.