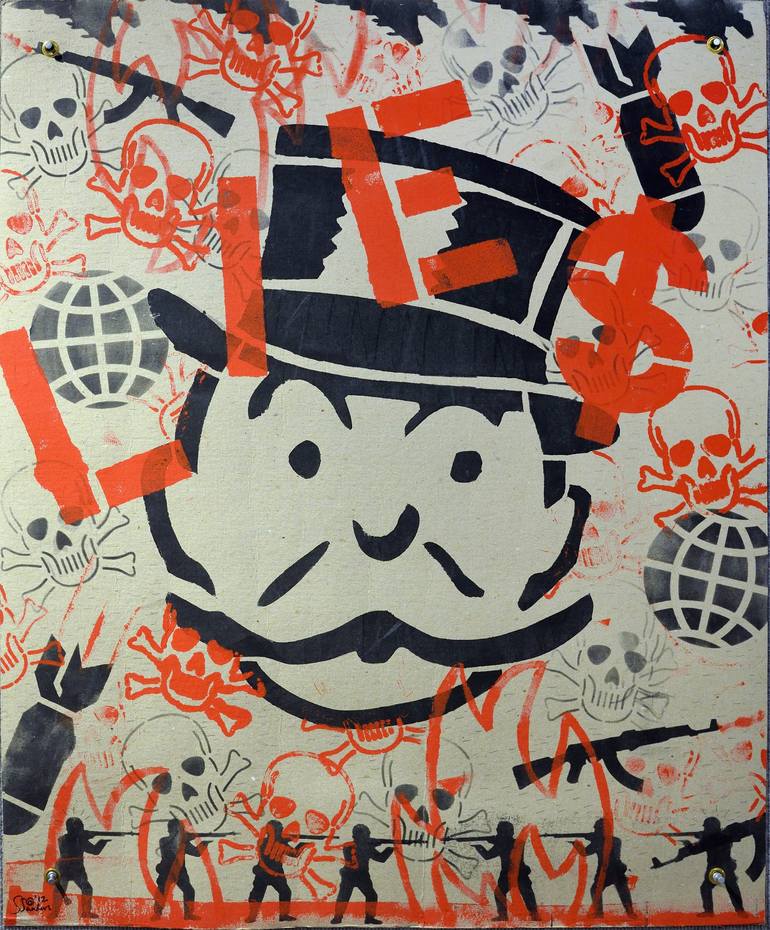

Sandy Sanders’ The Devil’s Kitchen is a searing, streetwise confrontation with the symbols of American capitalism and moral decay. Executed in acrylic with a stencil-like immediacy, the painting thrusts viewers into a feverish mix of cartoon imagery, propaganda motifs, and anti-war iconography. The centerpiece—a distorted, looming visage of the Monopoly Man—anchors a chaotic backdrop of skulls, soldiers, and fire. It’s an infernal parody of wealth and deceit, filtered through the language of graffiti and pop satire.

The work’s title, The Devil’s Kitchen, evokes a workshop of corruption, a metaphorical furnace where truth and ethics are cooked down into consumable lies. The canvas reads like a warning label for a poisoned world—one where entertainment, greed, and death have become indistinguishable ingredients in the recipe of modern life.

the pop face of deceit

Sanders’ use of the Monopoly Man—Mr. Moneybags, the tuxedoed mascot of an American board game—immediately positions the piece within a lineage of Pop Art and protest. But where Andy Warhol might have celebrated the neutrality of consumer imagery, Sanders weaponizes it. His appropriation is not about cool detachment; it’s about indictment.

The character’s familiar monocle and mustache, once symbols of old-world charm, are now rendered in stark black lines against a background teeming with red skulls. Around his face, the stenciled word LIE$ cuts through the surface like a brand. The substitution of the dollar sign for “S” is unsubtle, but purposefully so—it’s a blunt tool for a blunt truth: capitalism thrives on deception. Sanders’ visual vocabulary echoes the directness of street protests, where clarity and speed matter more than polish.

By fusing satire with menace, Sanders transforms an icon of leisure into an emblem of control. The Monopoly Man is no longer a game host; he’s the devil’s sous chef in this kitchen of corruption.

structure

Compositionally, the painting is both frenetic and deliberate. The eye ricochets between red skulls, black silhouettes, and the heavy contours of the central face. Sanders uses repetition as rhythm—skulls multiply like the body count of a forgotten war, soldiers march in a synchronized loop, flames crawl upward from the bottom edge. The repetition is hypnotic, evoking both advertising and propaganda, which rely on constant reinforcement to dull the viewer’s critical faculties.

Color is used with surgical precision. Red dominates the scene—not merely as an aesthetic choice, but as emotional punctuation. It’s the red of warning lights, blood, and moral emergency. Black, conversely, lends the work its structure—a visual authoritarianism that pins the chaos into place. Gray, the third player, fills the space between extremes, suggesting the fog of ambiguity where most political and moral corruption thrives.

Sanders’ brushwork, though masked by the precision of stencil patterns, reveals layers beneath the surface—ghostly traces of earlier forms, overpainting, and smudged symbols. These palimpsests contribute to the work’s sense of historical layering: capitalism as an accumulation of half-erased narratives and buried bodies.

visual

Below the Monopoly Man, a procession of silhouetted soldiers aims their rifles into unseen space. Their facelessness echoes the anonymity of state violence—the mechanization of killing in the name of profit. Around them, skulls repeat like corporate logos. Sanders collapses the distance between war and marketing, between death and design.

This interlacing of military and capitalist imagery recalls the visual strategies of artists like Barbara Kruger, Robert Rauschenberg, and Banksy. Yet Sanders’ tone is less ironic and more furious. His painting feels hand-to-hand, as if made in the heat of a political riot rather than a gallery studio. The result is both a visual essay and an emotional outcry.

The globe motif that appears beside the central figure situates the work in a globalized context. It’s a reminder that American capitalism’s reach is planetary, that the “kitchen” where these lies are cooked is not confined to U.S. borders. The imagery implies that every bomb, every brand, every policy exported abroad is part of the same meal being served—one flavored by control, greed, and selective amnesia.

from pop to protest

In its blending of familiar imagery and moral urgency, The Devil’s Kitchen occupies a unique space between Pop Art and political street art. The precision of its stenciling nods to commercial print aesthetics, yet its raw layering and confrontational message recall the immediacy of protest posters and urban graffiti. Sanders doesn’t seek to aestheticize dissent; he insists that it remain uncomfortable.

This approach situates him in the lineage of politically conscious artists such as Shepard Fairey and Peter Saul—artists who refuse to separate visual appeal from ethical consequence. Like them, Sanders understands the seductive power of icons. He uses them against themselves, turning symbols of entertainment into instruments of exposure.

The Monopoly Man, stripped of his cheerful capitalism, becomes the ultimate deceiver—the smiling mask that hides the machinery of exploitation. The skulls, once pirate emblems of rebellion, are now the wallpaper of complicity. Sanders’ inferno is not fantastical; it’s corporate, military, and disturbingly familiar.

idea

The stenciled word LIE$ is central to the painting’s impression. Its placement across the Monopoly Man’s face functions like a headline, a brand, and a scar all at once. The word performs triple duty: it names the deceit, quantifies it, and implicates the viewer in its economy.

In using typography as imagery, Sanders extends the visual grammar of protest art. Text becomes both message and form—a way to puncture the hypnotic surface of capitalist imagery. It breaks the silence of propaganda, forcing the viewer to confront the linguistic economy of deceit. The piece thus bridges the visual and the verbal, embodying a direct, unfiltered scream rather than a polite conversation.

flow

The Devil’s Kitchen does not offer redemption or resolution. It is not a painting of solutions, but of exposure. The flames licking upward at the bottom edge, the soldiers locked in endless aim, and the skulls filling every empty space—all suggest a closed circuit of destruction. Sanders’ world is one where deceit is self-perpetuating, where every lie feeds another.

Yet there is a strange vitality in the chaos. The raw energy of the composition suggests that within this inferno lies the potential for awakening. By overwhelming the viewer, Sanders denies passive consumption. You cannot look at The Devil’s Kitchen the way you glance at a poster—you must grapple with it.

In that sense, the work functions as both mirror and warning: a reflection of America’s capitalist mythology and a reminder of what happens when that mythology collapses under its own weight.

impression

Sandy Sanders’ The Devil’s Kitchen is a confrontation with comfort, a painting that replaces consumer nostalgia with political nausea. Through the weaponization of familiar symbols, Sanders exposes how deeply the aesthetics of capitalism have colonized the American imagination. His fusion of pop iconography, military imagery, and textual accusation transforms the canvas into a battleground—a place where lies and dollars burn side by side.

Ultimately, The Devil’s Kitchen is less a depiction of hell than an invitation to recognize the one we already inhabit. It’s a visual sermon about complicity, greed, and the dangerous seductions of comfort. In Sanders’ hands, the devil doesn’t need horns—just a top hat, a monocle, and a smile.

No comments yet.