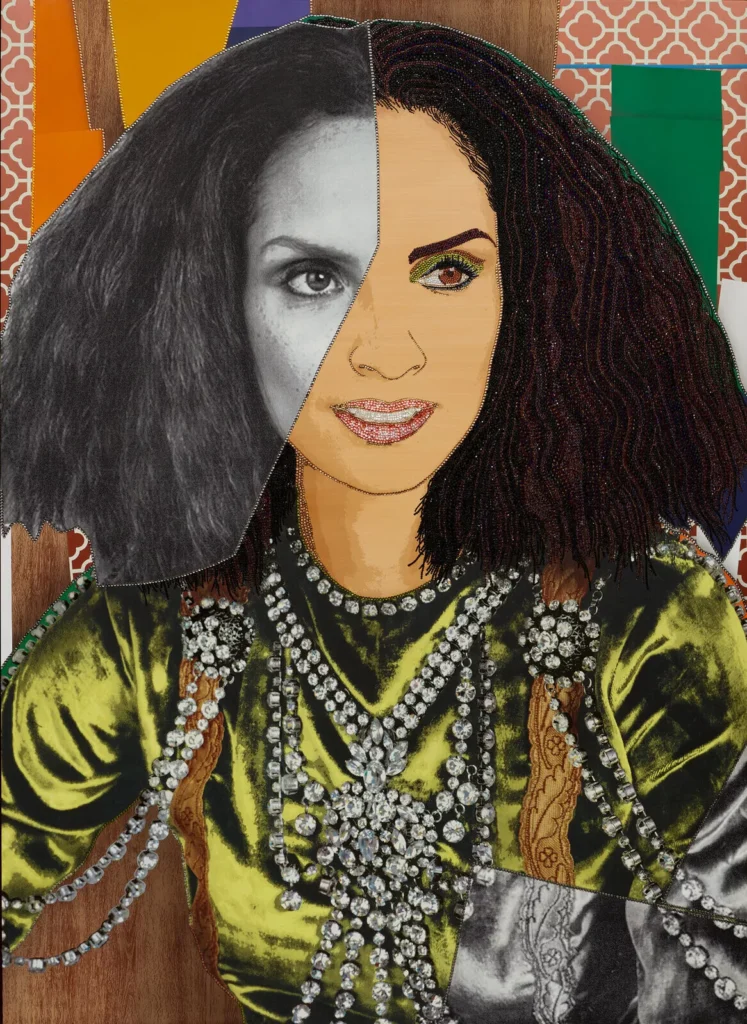

When standing before The Inversion of Racquel #2 (2021) by Mickalene Thomas, one is immediately met by the collision of light, texture, and history. It glows—literally and conceptually. Rhinestones, acrylic paint, and the gleam of wood form a surface that refuses passivity. This work does not whisper; it commands. It exists within the ongoing project that defines Thomas’s practice: to rewrite the canon of beauty, power, and identity through a Black feminist lens.

Thomas’s art expands beyond the decorative. Her rhinestones—often mistaken as mere embellishment—serve as ideological tools. They reflect, refract, and return the gaze. With The Inversion of Racquel #2, she inverts traditional hierarchies of looking and being looked at, turning her subject into both muse and monarch, sitter and sovereign.

context: from odalisque to empowerment

Mickalene Thomas’s rise as one of the most influential contemporary artists of the 21st century is rooted in her deep engagement with art history’s omissions. Her works reconfigure classical portraiture—think Matisse, Manet, Ingres—through the lens of Black femininity. Instead of women reclined as passive muses, Thomas’s figures radiate autonomy, adorned in patterns that evoke domestic intimacy while asserting authority.

The Inversion of Racquel #2 continues this project. The title itself suggests reversal—an intentional flipping of traditional narrative and power structure. In many ways, Thomas’s “inversions” act as acts of reclamation: they invert not only form but meaning, positioning Black women at the heart of visual discourse.

The “Racquel” in the series refers to Racquel Chevremont, Thomas’s longtime collaborator, muse, and partner, who frequently embodies the artist’s ideals of sensuality, intellect, and agency. This relationship infuses the work with emotional authenticity. Racquel is not objectified; she is a co-conspirator in the construction of image and meaning.

material

At the core of Thomas’s practice lies her fascination with materiality. In The Inversion of Racquel #2, the combination of rhinestones, acrylic, and wood transforms the painting’s surface into a multidimensional field. The rhinestones act as pixels of reflected light, each one catching the viewer’s gaze and scattering it—breaking the unity of perception. This fragmentation becomes a metaphor for identity itself: shimmering, layered, and ever-changing.

Acrylic paint provides density and opacity, balancing the rhinestones’ sparkle with painterly depth. The wooden panel grounds the image in warmth, its grain subtly visible beneath layers of color and light. It echoes a tactile world of domesticity and craft, connecting the work to the handmade traditions of quilt-making and collage—practices historically associated with Black women’s creativity.

The tactile surface invites proximity. It resists the cool distance of classical portraiture, demanding the viewer’s physical and emotional presence. The act of looking becomes participatory—each rhinestone reflects both the subject and the spectator.

concept

In The Inversion of Racquel #2, Thomas explores how identity and image can be reconstituted through form. The “inversion” functions on multiple levels: visual, cultural, emotional.

Visually, Thomas plays with mirror symmetry and reversal of orientation. The figure’s pose and surroundings are arranged in ways that suggest reflection—perhaps through a literal mirror, perhaps through metaphorical self-regard. The composition fractures traditional spatial hierarchies: patterns dominate backgrounds, color fields dissolve edges, and the subject merges with the environment. This strategy recalls Thomas’s interest in domestic interiors as sites of memory and power.

Culturally, inversion means reclaiming agency over representation. By turning the gaze outward—through the reflective surface of rhinestones—Thomas subverts the historical imbalance between the viewer and the viewed. Her subject is no longer contained; she projects presence.

Emotionally, the inversion gestures toward introspection. It’s not merely a portrait of Racquel—it’s a study in relational seeing. Thomas’s engagement with her subject oscillates between admiration, affection, and collaboration. The inversion, then, becomes a symbol of mirrored identities: artist and muse, self and other, creator and subject entwined.

reworking the canon

Mickalene Thomas’s dialogue with Western art history has always been deliberate. She does not reject the canon outright; she revises it from within. In The Inversion of Racquel #2, one can trace the echoes of 19th-century portraiture, yet every formal device is redirected toward new ends.

Her use of collage—layered patterns, fabrics, and surfaces—derives partly from Matisse’s decorative interiors, but Thomas infuses them with African diasporic textures: kente prints, retro upholstery, wallpaper motifs reminiscent of the 1970s domestic sphere. These are not nostalgic flourishes; they are mnemonic codes. They signal cultural memory, intergenerational aesthetics, and the politics of home.

In replacing the odalisque’s languid sensuality with a poised, empowered figure, Thomas rewrites the visual grammar of femininity. The resulting portrait fuses glamour and resistance. Rhinestones, once symbols of artifice, become emblems of self-definition. The figure dazzles, but not to seduce; she dazzles to assert her visibility.

view

Visibility in Thomas’s work is never neutral. In the art historical archive, Black women have been largely absent—or when visible, framed through colonial or exoticized perspectives. Thomas responds by making visibility a form of power.

Each rhinestone in The Inversion of Racquel #2 acts as a tiny lens of assertion. They collectively form an armor of luminosity, turning vulnerability into strength. The subject’s gaze, often direct and unflinching, confronts the viewer with dignity rather than invitation.

By employing materials associated with adornment, Thomas reclaims the aesthetics of the “glamorous” as sites of resistance. Her rhinestones challenge notions of high and low art, collapsing boundaries between fashion, craft, and fine art. This blurring destabilizes hierarchies of taste—a radical act within institutions still marked by Eurocentric standards.

Moreover, Thomas’s emphasis on Black femininity aligns her with broader movements in visual culture that center intersectionality and self-representation. Her subjects, including Racquel, embody a multiplicity that resists simplification. They are not archetypes but individuals situated within complex histories of race, gender, and beauty.

flow

The interiors of Thomas’s compositions are as significant as her figures. They evoke domestic spaces layered with color, texture, and personal symbolism—spaces that once served as private zones of self-fashioning for Black women, away from external scrutiny.

In The Inversion of Racquel #2, the interplay between the subject and her surroundings mirrors this dialogue between inner and outer life. The domestic backdrop becomes both a sanctuary and a stage, a place of safety and performance. Thomas understands that identity is constructed within such intimate architectures.

Her work connects these private aesthetics to public recognition, elevating the ordinary materials of home—wood, fabric, pattern—to the realm of high art. The result is an atmosphere that feels both personal and political, tender and monumental.

the body as light

What differentiates The Inversion of Racquel #2 from traditional portraiture is its play with illumination. Rhinestones do not simply decorate the body; they become its extension. The light that bounces off the surface seems to emanate from within the figure herself.

This literal and metaphorical radiance ties to Thomas’s ongoing fascination with self-love and transcendence. Her subjects often appear mid-transformation—emerging from shadow into brilliance, negotiating between visibility and self-possession. The glittering skin becomes symbolic of the multiplicity of selfhood.

Light here is political. In a world that has historically denied radiance to Black bodies, Thomas reclaims it. Her work reframes luminosity as liberation, insisting that Black beauty deserves to be seen, celebrated, and immortalized.

dialogue

The Inversion of Racquel #2 also operates as a temporal bridge. It references the past while engaging the present, and its material permanence hints at the future. Rhinestones, unlike precious gems, are democratic—they sparkle universally, accessible yet opulent. Their durability contrasts with their perceived cheapness, mirroring how Black culture often endures despite being undervalued.

The use of wood as support gives the painting an almost sculptural weight, reminding us of both historical craftsmanship and architectural grounding. In this sense, the work exists across dimensions: part collage, part painting, part artifact.

This multiplicity is Thomas’s answer to modern identity itself—fragmented, self-aware, yet whole in its contradictions.

emotion

At its heart, The Inversion of Racquel #2 is not just a political or aesthetic statement; it is also an act of love. The connection between artist and subject is palpable. Racquel Chevremont, as both muse and partner, embodies a shared vision of power and tenderness.

This emotional layer differentiates Thomas from the distant gaze of the male painter. She does not objectify her subjects; she celebrates their complexity. The portraits are conversations, not captures. Each rhinestone reflects intimacy, each brushstroke affirms presence.

By naming her subject directly, Thomas foregrounds individuality. Racquel is not an anonymous figure; she is a collaborator whose identity shapes the narrative. The inversion, then, extends beyond composition—it is an inversion of authorship, transforming muse into co-creator.

leg

Since its debut, The Inversion of Racquel #2 has been recognized as one of the pivotal works in Thomas’s ongoing examination of identity and representation. Critics have highlighted its blend of sensuality and scholarship—how it fuses formal innovation with social commentary.

In museum contexts, the piece challenges curatorial frameworks. Its materials blur categories: painting, sculpture, collage. Its subject blurs roles: personal muse, political icon, art-historical counterpoint. This hybridity mirrors the fluid identities of the subjects Thomas champions.

The work continues to inspire younger artists who see in Thomas’s practice a model for reimagining visibility—especially women of color redefining their relationship to portraiture and glamour.

impression

The Inversion of Racquel #2 (2021) encapsulates Mickalene Thomas’s enduring commitment to reconfiguring how Black women are seen, remembered, and celebrated. Through rhinestones and acrylic on wood, she constructs a visual language where beauty becomes resistance, intimacy becomes power, and reflection becomes revelation.

The painting is both mirror and manifesto. It radiates with the glitter of self-determination, echoing through the history of art as a reminder that the gaze itself can be inverted—that to look is also to be seen.

In a world still grappling with representation and belonging, Thomas’s work stands as an image of reclamation, shimmering in defiance of invisibility. Each rhinestone, each glint of light, declares that art—and identity—can be luminous, layered, and unapologetically complex.

No comments yet.