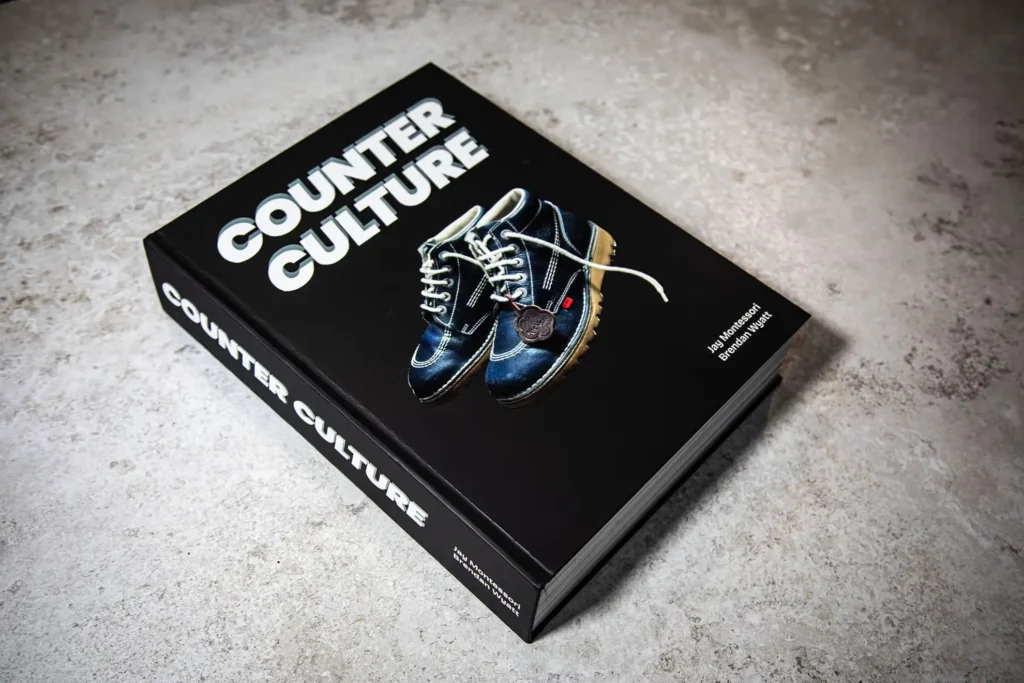

Few fashion books feel like they could crush a coffee table—physically and culturally—quite like Counter Culture. Written and compiled by Jay Montessori and Brendan Wyatt, this 600-page, 4.5-kilogram tome is less a publication and more a monumental object: part style archive, part love letter to a very specific British sensibility. With over 1000 historical reference images, it captures the evolution of UK street style from 1977 to 2002 through the eyes of two Liverpudlians who lived it, breathed it, and wore it.

The book is as much about the clothes as it is about the codes—the slang, the pride, the wit, the football chants, and the warehouse basslines. In that sense, Counter Culture is not just about fashion; it’s about the texture of British life itself. It’s a sociocultural time capsule, mapping a world where Stone Island badges were passports, Kickers were religion, and every jacket had a story.

lens

Montessori and Wyatt’s collaboration grows out of a shared youth spent in Liverpool during one of the most charged eras in UK subcultural history. Between 1977 and 2002, British style mutated through countless tribes: the casuals, mods, punks, ravers, and Britpoppers—each with its own uniform, attitude, and sonic backdrop. Liverpool, with its industrial grit and cultural swagger, was the perfect crucible for this evolution.

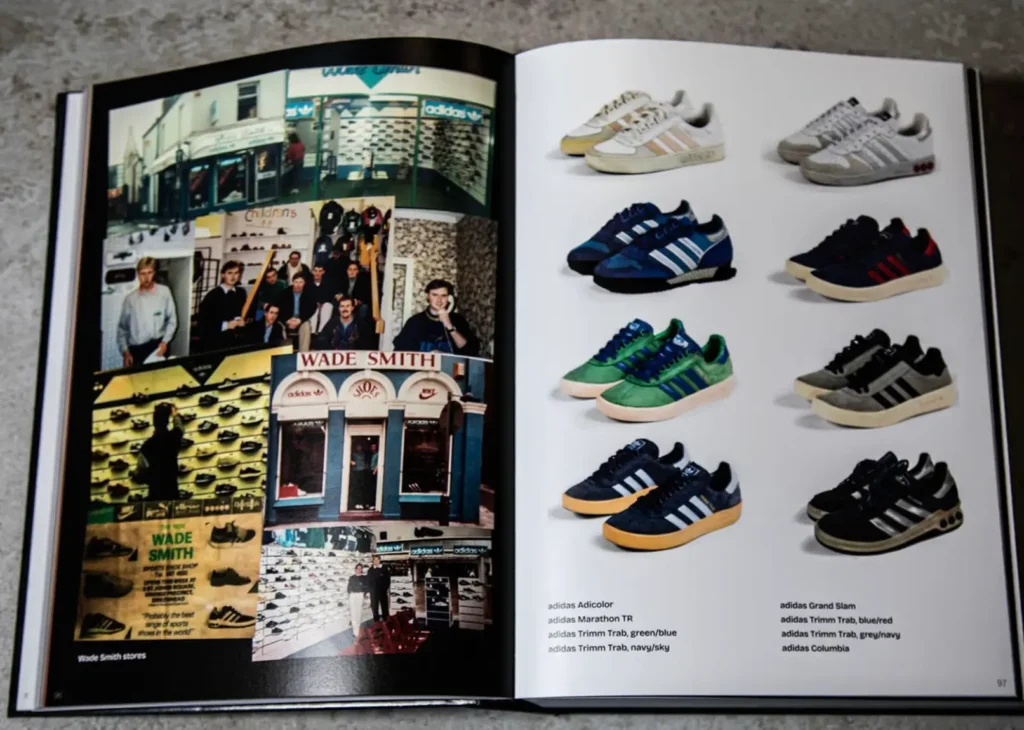

The authors make no attempt to generalize or romanticize. Instead, they zoom in on the intimate and the local—the street corners, schoolyards, football terraces, and record shops that shaped how people dressed and how they defined themselves. Every reference in Counter Culture feels lived-in. These aren’t historians reconstructing from afar; they are participants, still carrying the mental catalogues of Adidas drop dates and warehouse mixtapes.

flow

At the heart of Counter Culture lies obsession—specifically, the obsessive devotion to clothing as a language of belonging and rebellion. The authors’ personal collections form the spine of the book: Stone Island jackets, Fila tracksuits, Fiorucci denim, Aquascutum raincoats, and those iconic Kickers that defined 90s British playground cool.

Each garment is treated like an artifact. The photography captures every badge, crease, and label with forensic clarity, turning everyday items into objects of study. But the book avoids the clinical detachment of a museum catalogue. Its tone is raw, colloquial, occasionally hilarious, and deeply affectionate. The Liverpudlian dialect runs throughout, anchoring the text in authenticity.

That DIY energy—the sense that this book was built by collectors rather than designed by marketers—is what makes Counter Culture so compelling. It reads like a scrapbook of memories glued together with loyalty and mischief.

show

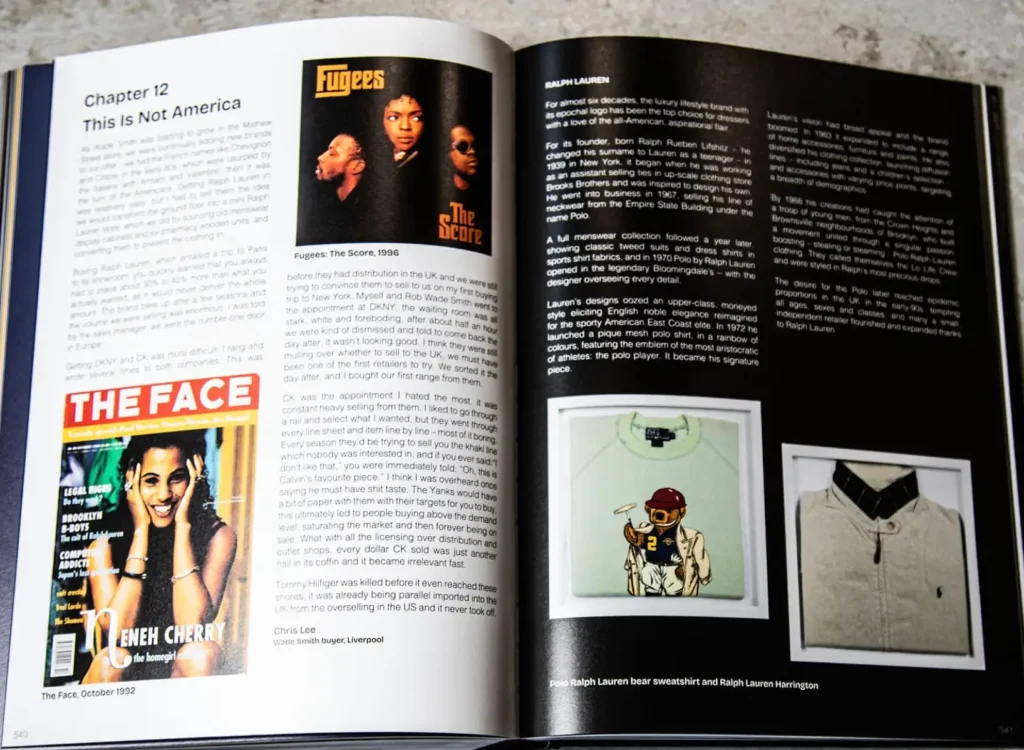

The period Counter Culture covers coincides with some of the most radical transitions in British youth identity. The late 70s saw the football terraces become fashion runways for working-class innovation, where Italian sportswear and designer outerwear became signals of allegiance and aspiration. The 80s and 90s exploded with the acid house scene, where casualwear morphed into rave uniform—baggy jeans, bright trainers, bucket hats, and oversized logos.

Montessori and Wyatt trace these transitions not through sociological analysis but through lived experience. Their words and images make visible how fashion crossed from the stadium to the street to the club. A Stone Island badge might have once symbolized tribal loyalty on match day, but by the mid-90s it was as likely to be seen under strobe lights at Cream or on a dancefloor in Manchester.

This fluidity—how working-class lads reinterpreted European luxury, how ravers adopted sportswear, how Britpop merged mod nostalgia with casual swagger—is where Counter Culture finds its rhythm. It celebrates fashion as the great British remix.

lang

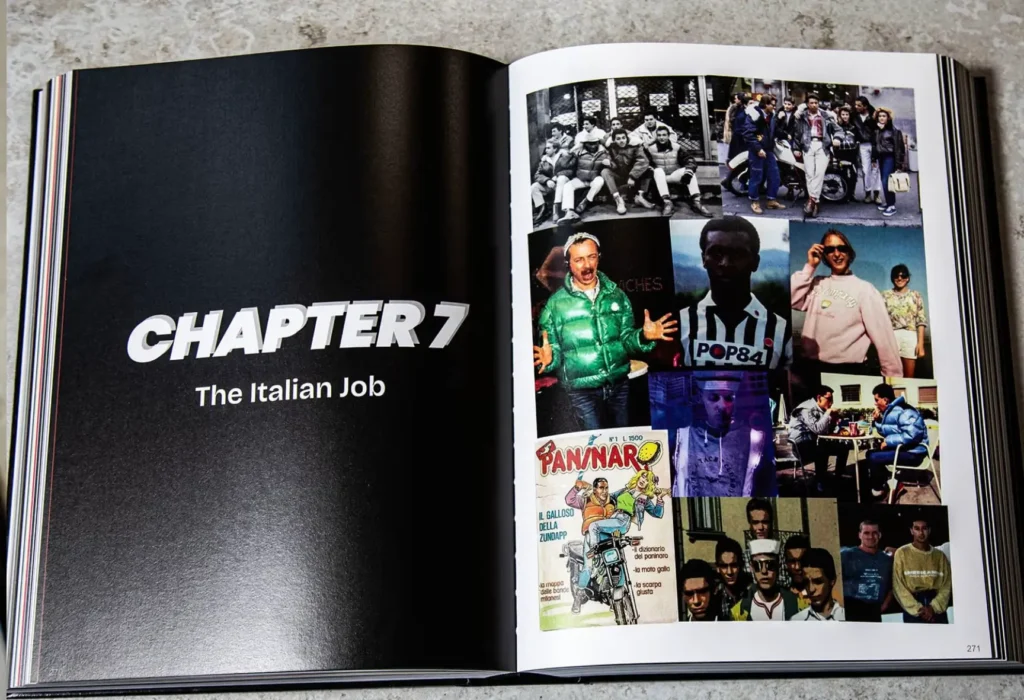

Visually, Counter Culture is overwhelming in the best way. The sheer density of images creates an almost cinematic experience—page after page of scanned Polaroids, flyers, wardrobe shots, and street portraits that feel like fragments of a collective memory. Each picture hums with context: the smell of rain on nylon, the hum of a Walkman, the sound of chants echoing off concrete terraces.

The book’s visual language mirrors its subject matter. It’s not polished editorial photography; it’s lived photography. There’s a tactile, grainy honesty that reflects the imperfect beauty of the era it documents. The layout mimics the messiness of memory—chaotic, layered, funny, and full of energy.

Even the typography and captions feel personal, like notes scribbled in the margins of adolescence. Phrases like “that lad’s trackie was boss” or “pure style, la” ground the project in regional voice and humor. The result is a visual slang—a design language that feels as culturally specific as the Scouse accent.

culture

To call Counter Culture a “fashion bible” might sound hyperbolic, but it earns the title. Its 4.5 kilograms are symbolic of weight in every sense. Physically, it’s massive. Culturally, it’s monumental. It brings structure to a history that was previously dispersed across wardrobes, memory, and oral storytelling.

The book bridges generational gaps too. For those who lived through the subcultures it documents, it’s nostalgic affirmation. For younger readers—fashion students, stylists, or streetwear archivists—it’s revelation. It provides the connective tissue between the terraces and today’s streetwear scene, revealing how brands like Stone Island, adidas Spezial, and CP Company gained their mythic resonance.

This is not fashion as luxury but fashion as identity—where clothing was less about status and more about statement.

sense

Liverpool sits at the book’s emotional core. The tone captures the city’s characteristic blend of pride, resilience, and humor. It’s full of in-jokes only someone raised in Merseyside would fully decode. But that local specificity becomes universal in feeling. Through the particularity of Liverpool’s streets, the book articulates the spirit of working-class Britain—a world where humor, style, and self-expression were forms of resistance.

The voice is cheeky but never cynical. Even when describing rough edges—violence on terraces, rivalry, police crackdowns—there’s affection. That warmth comes from two men who understand that style was never frivolous; it was survival, identity, and connection.

the DIY grandeur

What makes Counter Culture special is its paradoxical scale. On one hand, it’s intimate and homemade, stitched together from personal collections and firsthand memories. On the other, it’s monumental in scope—a 600-page encyclopedia of taste, tribalism, and transformation. That duality gives it emotional depth.

There’s grandeur in its DIY spirit. Every scanned photo, every caption feels like an act of devotion. It’s a reminder that cultural history doesn’t only live in museums or glossy magazines—it lives in bedrooms, record sleeves, football scarves, and family photo albums.

The book’s scale mirrors the intensity of obsession that drives collectors and fashion historians alike. In its enormity, Counter Culture becomes a portrait of British fandom itself: loving, relentless, and a little bit mad.

fin

Counter Culture isn’t just a book; it’s a time machine. It captures the pulse of British subculture not through nostalgia but through precision—every jacket, every label, every anecdote rendered with obsessive fidelity. Jay Montessori and Brendan Wyatt have created a definitive document of how style and identity evolved across a quarter century of working-class Britain.

It’s a story about pride and playfulness, about how a generation turned clothes into language. Whether you’re flipping through its pages for academic study, aesthetic pleasure, or personal memory, the feeling is the same: you’re holding history in your hands.

Weighing 4.5 kilograms, Counter Culture demands space on your table—and in the conversation about how fashion and culture intertwine. It’s the visual equivalent of a stadium chant and a warehouse beat rolled into one: loud, local, loving, and entirely unforgettable.

No comments yet.