In the earliest years of hip-hop, long before record deals, magazine covers, radio rotations or global tours, the culture existed in a hyperlocal loop: the block, the rec room, the park, the gymnasium, the community center. These spaces weren’t just where hip-hop happened — they were hip-hop. And the only record of those nights, those jams, those explosive moments of cultural invention, were the handbills tacked to light poles and corner stores: the flyers.

Few people on Earth understood the importance of those slips of paper better than Buddy Esquire.

Before hip-hop was an industry, before it had a visual language recognized worldwide, before album covers or logos or merchandise could carry its aesthetic into the mainstream, it had Buddy Esquire. He built hip-hop’s first graphic identity in real time, for real people, under real pressure. His flyers were the earliest visual codex of the culture — a record of names, dates, spaces, crews, DJs, MCs and energy that otherwise would have vanished into the Bronx night.

Today, collectors and historians agree: hip-hop flyers are among the most elusive artifacts in the entire culture. Designed for a moment, distributed by hand, destroyed by weather, taped over, tossed away, buried in shoeboxes. They weren’t meant to survive. Most didn’t.

But the ones that did survive — especially those created by Buddy Esquire — are priceless cultural fossils. They show the earliest shape of hip-hop, before the machine, before the myth, before anyone imagined what it could become.

flow

Long before he became a design legend, Buddy Esquire was a graffiti writer. He tagged as ESQ, navigating trains, walls and stairwells in the Bronx while developing the sharp lines and typographic instincts that would later define his flyers. Graffiti gave him an eye for stylization; the streets gave him an eye for speed.

Block parties were spontaneous, last-minute and endlessly shifting. Venues changed. Crews changed. Headliners changed. And flyers had to reflect that chaos — often overnight.

Esquire made his first flyers in 1977, just as the ecosystem of DJs and MCs was expanding from local fame to borough-wide notoriety. The genre had no formal infrastructure yet. Promoters were teenagers. DJs were neighborhood celebrities. And Esquire was both a witness and an organizer, using his artistic instincts to help shape how the world would first visualize hip-hop.

In an era without Photoshop, Illustrator, digital typesetting or desktop printing, Esquire worked with whatever resources he could gather: Prestype letters, rub-on transfers, photo offset printing, scissors, glue sticks, markers, and a mastery of the cut-and-paste method. His flyers weren’t crafted in studios; they were assembled in apartments, on kitchen tables, inside crowded rooms filled with records and friends. But he treated each one as a work of art.

He was never just making announcements — he was crafting aesthetic authority.

signature

Esquire is most associated with what he called “Neo Deco” — a style blending Art Deco geometry with the rough grain of street culture. Think sharp angles, chrome illusions, futuristic borders, dramatic lettering, frames that looked pulled from cinema marquees.

He created visual importance where none formally existed.

Hip-hop was still dismissed by outsiders as noise, as a fad, as chaos. But Esquire’s flyers countered that narrative. They evoked elegance, sophistication, structure. They made DJ sets and MC battles feel like headline events at grand theaters.

His flyers were aspirational architecture for a culture still being built.

Esquire designed with a sense of hierarchy — names were arranged with a seriousness typically reserved for Broadway posters or boxing match bills. Groups like The Funky 4 + 1, Cosmic Force, The Jazzy Five, and Cold Crush Brothers weren’t just local acts; on an Esquire flyer, they looked like stars.

And that mattered.

Representation mattered.

Perception mattered.

The Bronx was burning metaphorically and literally, but Esquire designed like it was rising.

show

Hip-hop’s earliest moments weren’t documented by institutional photographers or film crews. There were no official media outlets. No press kits. No one outside the Bronx was paying attention yet. In that vacuum, flyers became the ledger of the culture.

Esquire’s designs cataloged the timeline:

Who played where.

Which crews battled.

Which DJs controlled which rooms.

Which rec center, school gym, park, or community building came alive that night.

And because hip-hop was constantly moving — gyms in Mount Eden, basements on Jerome Avenue, parks on Sedgwick, roller rinks, abandoned lots — the flyers were often the only evidence that certain events ever happened.

Without them, entire chapters of hip-hop history would be undocumented.

Esquire, unknowingly, became the first visual historian of the culture. His handbills were more than advertisements. They were time capsules.

stir

One of the most fascinating aspects of Esquire’s work was the speed required. Promoters often secured venues at the last second. DJs wanted their names larger. Crews demanded placement. The weather changed. Somebody’s cousin offered up a basement. A school janitor agreed to open a gym for $50. A power outage pushed a jam to a new block.

Esquire was always ready.

He worked overnight, racing against time, cutting and pasting until dawn, running to downtown print shops to get 500 or 1,000 copies, then personally hitting the streets to distribute them.

Hip-hop in the ’70s and early ’80s was fully analog. Everything — the music, the promotion, the movement — was handmade. Esquire embodied that ethos.

He wasn’t just making flyers. He was making infrastructure.

the endure

Most early hip-hop imagery was ephemeral: murals were buffed, trains were cleaned, parties were undocumented, tapes were lost. But Esquire’s flyers stuck in people’s memory not only because they were everywhere, but because they were striking.

Collectors today describe his work as “museum-grade street culture.”

Designers study his layouts for lessons in pre-digital ingenuity.

Curators analyze his typography as early Afro-diasporic graphic innovation.

His flyers endure because they sit at the exact intersection of necessity and artistry. They’re reminders that the culture was handmade before it was commodified.

And more than that, they capture the emotion of early hip-hop — the electricity of possibility, the sense that something massive was being invented in real time.

Esquire caught that feeling on paper.

culture

Throughout the late ’70s and early ’80s, Buddy Esquire designed over 300 flyers — perhaps more, depending on lost pieces and undocumented work. They advertised shows with:

Grand Wizard Theodore

Kool Herc

Kurtis Blow

Grandmaster Flash

The Cold Crush Brothers

The Fantastic Five

The Jazzy Five

Cosmic Force

Eddie Cheeba

Kool Here

and dozens more pioneers.

These flyers function today like Rosetta Stones. They reveal the spread of crews. The rise of certain DJs. The influence of certain parks. The cross-pollination between neighborhoods. The networks that tied the Bronx, Manhattan and Harlem into a new cultural geography.

For hip-hop historians, each Esquire flyer is an archaeological shard.

For designers, each is a masterclass.

For fans, each is a piece of magic.

leg

Buddy Esquire passed away in 2014, leaving behind a legacy still being fully understood and appreciated. In life, he did not receive the widespread acclaim that his influence demanded. His work was undervalued, overlooked, often unpaid, often taken for granted — a familiar story in the early hip-hop economy.

But in the years since his passing, museums, galleries, and archives have rediscovered him. Institutions now treat his flyers as cultural treasures. Exhibitions have framed his pieces alongside the pioneers he promoted. Scholars have cited him as a foundational figure in African American design history.

Yet preservation remains urgent.

Flyers were not made to last.

Most are fading, tearing, yellowing, or disintegrating.

Those that survive deserve conservation — and celebration.

Esquire’s legacy is not merely about design. It is about the fragility of culture when culture is improvised. It is about how easily history can vanish if not intentionally kept. It is about giving credit to the builders whose contributions were not recorded because the world didn’t yet understand what they were building.

fin

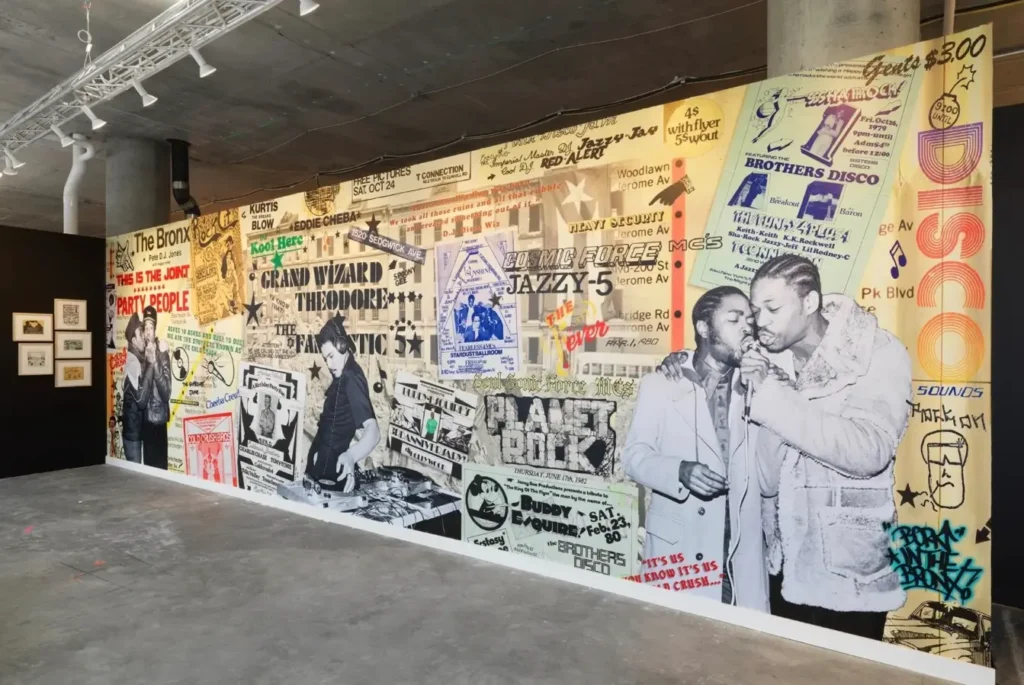

The mural you see — filled with his flyers, photographs of early MCs, typography, graffiti flourishes, and ephemera from the Bronx — captures what his work meant to the culture. It is not simply nostalgia. It is a map. A map of where hip-hop came from, who made it, and how it moved.

Buddy Esquire didn’t just design flyers.

He designed identity.

He designed aspiration.

He designed history as it was happening.

His work endures because he made the streets visible. He made the culture legible. He gave hip-hop its first graphic voice.

And that voice continues to echo — through print, through walls, through galleries, through archives, and through the generations still discovering the flyers that once lived only on Bronx poles and hallway doors.

Esquire may be gone, but the culture he helped visualize is eternal.

No comments yet.