In 1980, Andy Warhol completed one of his most quietly radical bodies of work: Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century. At first glance, the series appears deceptively straightforward—ten iconic Jewish figures rendered in Warhol’s signature silkscreen style. Yet within the portfolio, Albert Einstein occupies a singular position. More than a scientist, Einstein had become a symbol: of genius, exile, moral conscience, and the twentieth century’s uneasy relationship with progress. Warhol’s Albert Einstein (Unique Trial Proof) is not merely a portrait of a man—it is a meditation on how history turns individuals into images, and how images outlive truth.

Where earlier Warhol works consumed celebrities, commodities, and disasters, Einstein represents something subtler: the commodification of intellect itself.

flow

By the late 1970s, Warhol was no longer the enfant terrible of American art. He was an institution—wealthy, prolific, omnipresent. Yet this period marked a reflective turn in his practice. The Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Centuryportfolio was conceived as both homage and provocation, assembling figures whose cultural significance had transcended their individual disciplines.

The portfolio includes:

-

Albert Einstein

-

Sigmund Freud

-

Franz Kafka

-

Golda Meir

-

Martin Buber

-

Louis Brandeis

-

George Gershwin

-

Sarah Bernhardt

-

The Marx Brothers

This was not a religious project, nor a historical survey in the academic sense. Instead, Warhol selected figures who had been transformed by media, myth, and repetition—individuals whose faces had become shorthand for ideas larger than themselves.

Einstein, perhaps more than any other, had already crossed that threshold long before Warhol touched his image.

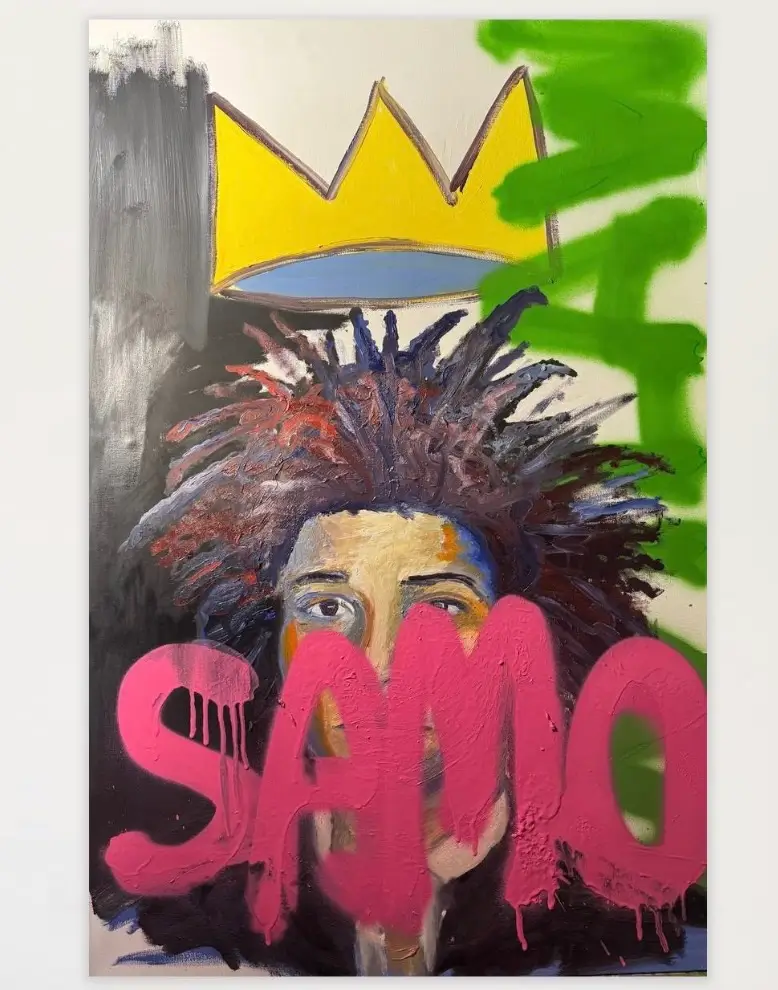

icon

Albert Einstein’s likeness is among the most recognizable in modern history. The wild hair, heavy eyelids, and distant gaze have become visual clichés of genius. By the mid-twentieth century, Einstein had ceased to be merely a physicist; he was a moral authority, a symbol of displaced brilliance, and a counterweight to the militarization of science.

Warhol understood this instantly.

In choosing Einstein, Warhol was not engaging with relativity or physics. He was engaging with Einstein the image: the refugee intellectual, the pacifist scientist, the man whose discoveries helped shape a world he later feared. This duality—creation and consequence—aligns seamlessly with Warhol’s own fascination with fame, responsibility, and detachment.

trail

The designation Unique Trial Proof is crucial. Unlike standard editioned prints, trial proofs exist outside the logic of mass production. They capture experimentation, hesitation, and variation—qualities often absent from Warhol’s reputation as a mechanical producer.

In the Einstein trial proof, color relationships feel provisional rather than fixed. There is a sense of testing identity itself: how far the image can be pushed before it becomes abstraction, how much distortion the subject can endure before recognition collapses.

This matters because Einstein’s public identity was already unstable—pulled between scientist, celebrity, and moral voice. The trial proof amplifies this instability, making the portrait feel less like a definitive statement and more like a question.

style

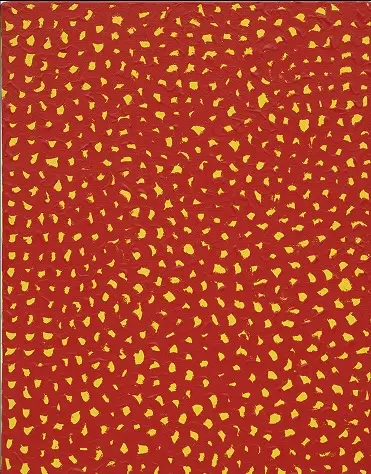

Warhol’s silkscreen technique operates as both reproduction and erasure. By working from photographic source material—often press images—Warhol embraced the flattening effect of mass media. Fine detail dissolves. Shadows become graphic shapes. Emotion is stripped down to contrast and outline.

In Albert Einstein, this flattening is deliberate. Warhol does not attempt psychological depth in the traditional portrait sense. Instead, he presents Einstein as a surface—a recognizable signal rather than an intimate presence.

This is not disrespect. It is diagnosis.

Warhol understood that history remembers through repetition, not nuance. By rendering Einstein as a silkscreen icon, he mirrors the way society already consumed him.

show

Color in the Einstein portrait is restrained compared to Warhol’s more flamboyant works. The palette often favors muted tones punctuated by sharp contrasts—suggesting intellect over spectacle.

Hair and facial contours are exaggerated, while eyes recede into silhouette. The effect is paradoxical: Einstein appears both hyper-visible and emotionally distant. The genius is on display, yet unreachable.

This tension reflects the broader twentieth-century anxiety around knowledge—how breakthroughs promise enlightenment while enabling destruction. Warhol does not moralize; he simply stages the contradiction visually.

fwd

Warhol famously avoided overt political commentary, even when working with politically charged subjects. Einstein, a vocal critic of nationalism and nuclear weapons, could have been framed as a moral figurehead. Warhol refuses this temptation.

Instead, he maintains emotional neutrality—neither celebrating nor critiquing Einstein’s legacy. This restraint is itself political. By withholding interpretation, Warhol highlights how culture consumes meaning without responsibility.

Einstein becomes an image among images—no more protected from commodification than Marilyn Monroe or Mao Zedong.

leg

By 1980, Warhol was acutely aware of his own legacy. The Ten Portraits series can be read as a mirror—an examination of how individuals are remembered not for complexity, but for recognizability.

Einstein’s portrait reflects Warhol’s own fears: that depth dissolves under repetition, that history remembers faces more than ideas. In this sense, the work is autobiographical. Warhol and Einstein are linked not by discipline, but by their transformation into symbols.

idea

Einstein died in 1955. Warhol died in 1987. Yet their images persist—reproduced endlessly across textbooks, posters, advertisements, and screens.

Warhol’s Albert Einstein accepts this immortality without romance. It does not rescue Einstein from simplification; it exposes simplification as inevitable. In doing so, it becomes one of Warhol’s most intellectually honest works.

The portrait does not explain genius. It shows what happens to genius once it enters history.

fin

Albert Einstein (from the Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century portfolio) stands as a quiet cornerstone of Warhol’s late practice. It replaces spectacle with contemplation, color with restraint, and personality with symbol.

In Warhol’s hands, Einstein is not a scientist, a refugee, or a moral voice—he is an image under pressure. A face tested by repetition. A mind flattened by fame.

And in that flattening, Warhol reveals the truth of the twentieth century: that even the most profound ideas eventually become surfaces.

No comments yet.