“The Breakfast from Hell” (2014), an archival pigment print by the provocative British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman, represents a key work within their broader oeuvre, which often confronts viewers with images of grotesque horror and satirical critiques of modern society. Known for their transgressive approach, the Chapman brothers have long sought to challenge societal norms, using shock and dark humor as tools to reveal uncomfortable truths about violence, human nature, and the disturbing legacies of history. This print, with its unsettling mix of seemingly benign imagery—breakfast—and nightmarish violence, serves as a potent encapsulation of their distinctive approach to art. In this critical explication, we will delve into the visual, thematic, and symbolic layers of “The Breakfast from Hell”, exploring its connections to art history, its commentary on contemporary culture, and its place within the Chapman brothers’ body of work.

To understand “The Breakfast from Hell”, it’s essential to situate the work within the broader context of the Chapman brothers’ career. Jake and Dinos Chapman emerged as part of the YBA (Young British Artists) movement in the 1990s, alongside figures such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin. The YBA group became famous for their use of shock tactics, employing controversial imagery and materials to question art’s role in reflecting societal concerns. For the Chapmans, these concerns often focused on the darker aspects of human behavior, drawing inspiration from the violent, the grotesque, and the absurd.

Their early works, such as “Disasters of War” (1993), a series of reimagined prints based on Francisco Goya’s original “Los Desastres de la Guerra” (1810–1820), offered a clear indication of their artistic concerns. By taking Goya’s visceral depictions of war and reworking them with grotesque and surreal details, the Chapmans highlighted the cyclical and repetitive nature of human violence. This strategy of appropriating art historical sources and infusing them with nightmarish elements continues in “The Breakfast from Hell”, which, while seemingly less directly rooted in historical allusion, nonetheless explores the same themes of destruction, chaos, and the perversion of the everyday.

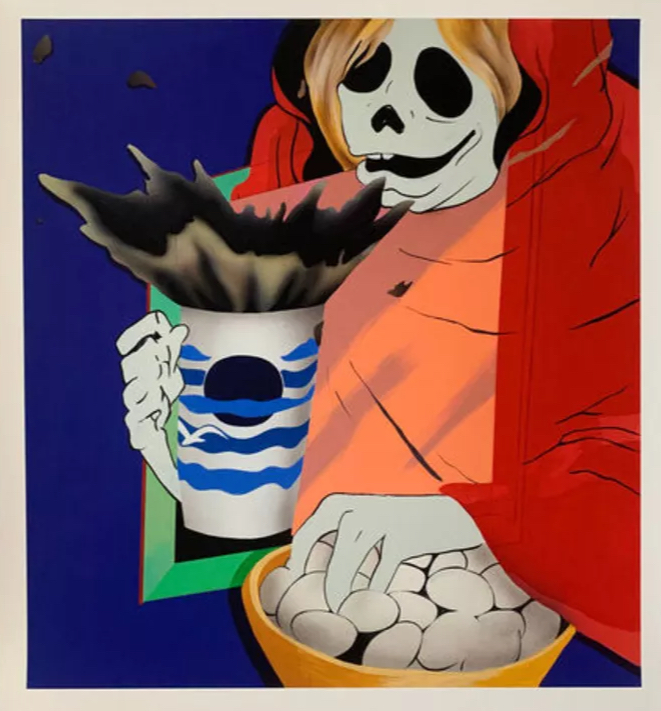

At first glance, “The Breakfast from Hell” presents an image that contrasts the banal with the horrific. The title alone sets the stage for this tension between the ordinary and the monstrous, as it juxtaposes “breakfast,” a quotidian and even comforting ritual, with “hell,” a realm of suffering and torment. The visual composition of the print reinforces this contrast: within a scene that might initially evoke the coziness of a breakfast table, we are confronted with surreal, grotesque figures that invoke fear and disgust.

The use of archival pigment printing in “The Breakfast from Hell” allows for a high level of detail and tonal richness, giving the work an unsettling realism. The figures, rendered with disturbing clarity, seem to hover between the real and the surreal, blending human and monstrous forms. The crispness of the printing process intensifies the viewer’s engagement with the subject matter, forcing us to confront the nightmarish elements head-on rather than allowing them to dissolve into abstraction or ambiguity. This use of hyperrealism draws the viewer in, challenging them to linger over details that might, in another context, evoke revulsion or avoidance.

In “The Breakfast from Hell”, the breakfast table becomes a symbolic site where violence, consumption, and civilization intersect. Breakfast, in most cultural contexts, is associated with routine, nourishment, and the start of a new day. However, by introducing violent and monstrous imagery into this scene, the Chapman brothers subvert these associations, suggesting that even the most mundane and supposedly innocent aspects of human life are not free from the taint of violence and horror.

This thematic subversion can be read as a commentary on the hidden undercurrents of civilization. In the context of contemporary Western society, the breakfast table might be seen as a symbol of domestic stability and normalcy. Yet, as the Chapman brothers seem to argue, this stability is often built on the suppression or externalization of violence. The grotesque figures that invade the breakfast scene may represent the repressed forces of chaos that underlie the veneer of civilized life. In this sense, “The Breakfast from Hell” recalls the Freudian concept of the “return of the repressed,” in which suppressed desires, fears, and traumas resurface in distorted, often monstrous forms.

Like much of the Chapmans’ work, “The Breakfast from Hell” can be seen as a continuation of, and response to, a long tradition of grotesque and satirical art. The grotesque, as an artistic mode, has roots in the Renaissance, where artists like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder used strange, nightmarish imagery to comment on human folly, sin, and societal collapse. Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (c. 1490–1510), in particular, shares thematic affinities with “The Breakfast from Hell”. Both works employ bizarre, often horrifying figures to critique the moral and spiritual decay of humanity. The Chapman brothers’ use of breakfast as a focal point could be seen as an extension of Bosch’s tactic of embedding horror within seemingly innocent, everyday activities, thereby forcing viewers to confront their own complicity in the darker aspects of human nature.

Additionally, “The Breakfast from Hell” evokes the satirical spirit of 18th-century British artist William Hogarth, whose series “The Rake’s Progress” (1732–1734) and “Marriage A-la-Mode” (1743–1745) exposed the moral degradation of the upper classes through narrative scenes of excess, debauchery, and eventual ruin. While the Chapman brothers’ work is less narrative-driven than Hogarth’s, it shares his interest in the intersection of civilization, consumption, and moral decline.

On a broader level, “The Breakfast from Hell” can be read as a critique of consumer culture and the disconnection between everyday consumption and global suffering. The breakfast scene—normally associated with middle-class comfort—becomes a grotesque spectacle, suggesting that the ease and safety of domestic life in the West may be complicit in systems of exploitation and violence. The monstrous figures that populate the print may represent the unseen consequences of consumerism: environmental destruction, labor exploitation, and the perpetuation of global inequalities.

The use of violent and grotesque imagery also invokes a critique of media consumption. In an age where images of violence and suffering are often consumed passively through news and entertainment media, the Chapman brothers’ work forces viewers to confront the disturbing reality of what they might otherwise ignore. By placing this horror within the intimate, familiar setting of a breakfast scene, “The Breakfast from Hell” disrupts the viewer’s sense of distance from the violence that permeates the world. It becomes impossible to compartmentalize or ignore.

“The Breakfast from Hell” is a quintessential example of the Chapman brothers’ provocative, transgressive approach to art. Through their use of grotesque imagery and symbolic subversion, they compel viewers to confront the hidden violence that underpins modern civilization. Drawing on a long tradition of satirical and grotesque art, the Chapmans offer a darkly humorous but deeply critical commentary on the tensions between civilization and chaos, consumption and destruction, and routine and horror.

By juxtaposing the ordinary with the monstrous, “The Breakfast from Hell” forces us to question the stability and innocence of our own everyday lives. What horrors, the Chapmans ask, lurk beneath the surface of our routines? How complicit are we in the violence that sustains our comforts? In forcing these uncomfortable questions, the Chapman brothers reaffirm their position as artists unafraid to challenge the status quo, using shock and discomfort to provoke deeper reflection on the human condition.

No comments yet.