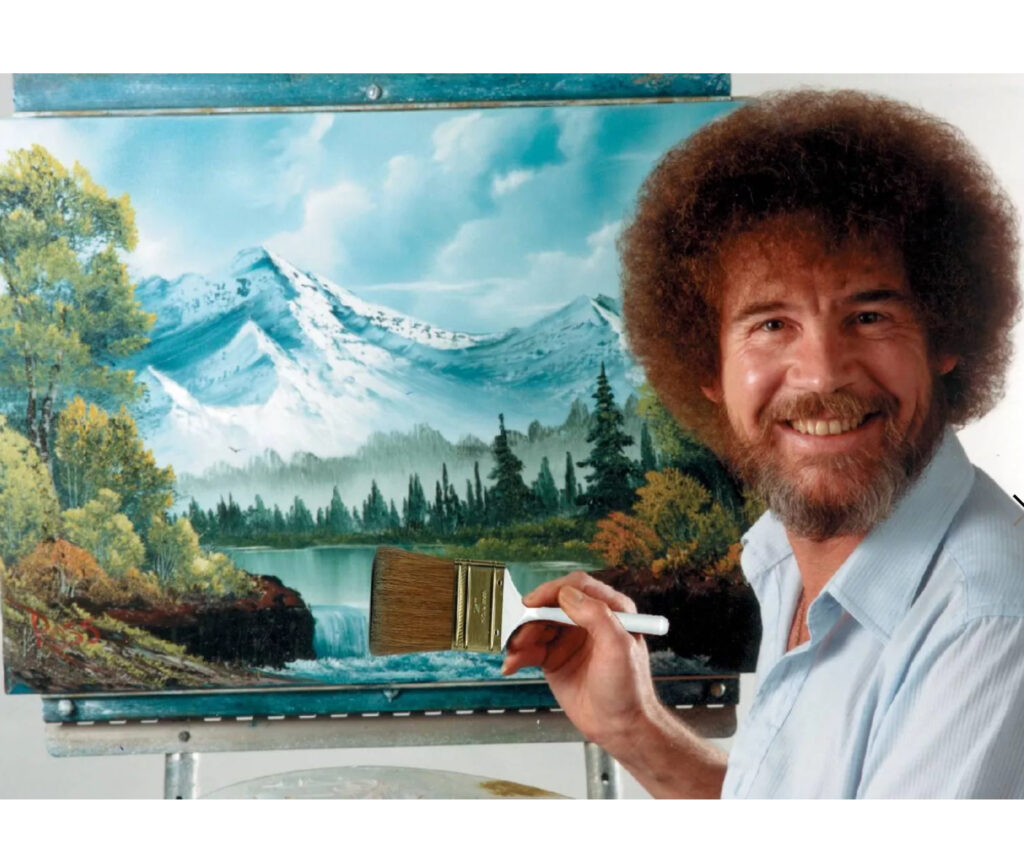

For much of his life, Bob Ross was known more for his hair and voice than for his brushstrokes. His signature perm, whisper-soft delivery, and unflappable calm were the hallmarks of The Joy of Painting, the PBS instructional program he hosted from 1983 to 1994. Week after week, viewers tuned in as Ross turned blank canvases into vibrant landscapes in under 30 minutes. It was television that taught a nation to paint — not just as craft, but as catharsis. Yet for all the cultural saturation of Ross’s persona, it’s only in recent years that his actual paintings have crossed the threshold from populist artifact to coveted collectible.

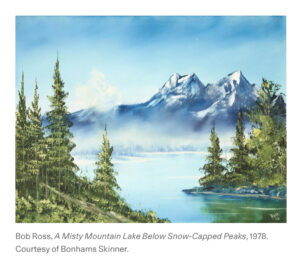

In September of last year, Bonhams Skinner made headlines when two original Bob Ross paintings were auctioned — one fetching $32,000 and the other $51,200, including fees. It marked the first time Ross’s works appeared at a major auction house. To seasoned art collectors, these numbers may seem modest, but for a figure whose paintings were never intended for market circulation, the moment signaled a radical shift. Ross is being reconsidered — not just as a soothing voice in the background of American life, but as an artist of historical and emotional resonance, one whose cultural gravity is finally being priced in.

The Painter Who Never Sold

Ross painted more than a thousand original works during his lifetime, the majority of which were created for The Joy of Painting. But unlike most artists who sell to make a living, Ross gave his works away — to fans, to PBS stations, to charity. The business behind Ross was never about scarcity or exclusivity. It was about accessibility. His “wet-on-wet” technique — or alla prima — allowed for entire paintings to be created in real-time, with layers of wet paint blended together directly on the canvas. It wasn’t a method built for archival longevity or gallery prestige; it was built for democratized artmaking.

Ironically, that very philosophy made his paintings scarce in the art market. For decades, Ross originals were practically absent from auctions, museum shows, and dealer circuits. He existed in a space parallel to the traditional art world — admired, adored, but never appraised. That’s part of what makes the Bonhams Skinner sale so symbolic. It’s not just the valuation of two paintings. It’s the engendering of Ross into the genealogy of American collectible art.

Nostalgia Meets Scarcity

Collectors often chase not just the work itself, but what the work evokes. And few figures conjure as specific and enduring a cultural memory as Bob Ross. In a time when the art market has been increasingly fueled by emotion, memory, and parasocial connection — see the boom in Mr. Rogers memorabilia, or the spike in mid-century children’s book illustrations — Ross’s aesthetic has found renewed relevance.

The demand isn’t only about beauty or technique. It’s about emotional resonance. Ross’s paintings are imbued with the very calm he exuded on camera. His skies don’t rage. His trees do not threaten. Even his “happy little accidents” are imbued with a sense of natural order. In a climate of uncertainty and digital chaos, his work represents something enduringly analog, tactile, and comforting. That emotional component is increasingly essential to collecting today — especially among millennial and Gen X buyers who grew up with Ross as a kind of spiritual uncle figure.

But more importantly, there simply aren’t many Ross originals available. According to the Smithsonian, many of Ross’s paintings — including duplicates he painted off-screen for instructional purposes — are owned and archived by Bob Ross Inc., the company that has managed his intellectual property since his death in 1995. These works are largely not for sale, and the company has historically prioritized brand preservation over art commerce. That has created an ironic inversion: the man who made painting feel abundant now occupies an art market category defined by scarcity.

A Cultural Artifact Beyond Irony

For years, Bob Ross was subject to a kind of kitsch framing. His voice, mannerisms, and even his paintings were often reduced to punchlines — think T-shirts with “No mistakes, just happy accidents” or novelty mugs featuring frolicking squirrels. He became part of meme culture, a visual soundbite in the ever-looping churn of internet ephemera. But as with many icons initially cast as nostalgic curios, there came a tipping point — a moment when ironic appreciation gave way to genuine reverence.

What’s occurring now is not unlike the art world’s evolving relationship with Norman Rockwell. Once dismissed as sentimentalist and out of touch with modernity, Rockwell is now enshrined as a chronicler of mid-century American life. Ross, too, is increasingly being viewed not as a novelty, but as a folk modernist of sorts — someone who bypassed the gatekeepers and reached the American public directly, one brushstroke at a time.

The Rise of the Vernacular Master

Ross belongs to a lineage of self-taught or outsider artists who have become reappraised through the lens of cultural history. While he did receive training — most notably during his time in the Air Force, where he learned to paint Alaskan landscapes — he rejected the elitism of academic technique. Instead, he positioned himself as an equalizer. His genius was not only in painting, but in teaching others to believe they could do it too.

The very premise of The Joy of Painting was antithetical to the art market’s obsession with uniqueness and mastery. Yet it is precisely that ethos — the way Ross flattened the hierarchy between artist and viewer — that now feels radical in hindsight. In valuing collective creativity over individual prestige, Ross became something of an unintentional subversive. Today, as contemporary artists re-engage with ideas of accessibility, process, and participation, Ross appears less like a peripheral figure and more like a precursor to social practice art.

The Auction House Seal of Legitimacy

The auction of Ross’s paintings at Bonhams Skinner marked more than a monetary milestone. It represented a symbolic validation. Auction houses serve as both arbiters and accelerators of taste. They don’t just respond to markets; they shape them. To see Ross’s name in an auction catalogue — not as memorabilia but as fine art — is to place him in the same breath as traditional painters whose works have long occupied that hallowed terrain.

And what’s even more significant is that these paintings were not recent discoveries. They were classic Ross works — snowy cabins, moody forests, layered clouds — the very imagery he produced live on-air. They were not reinvented for the market. They didn’t need to be. Their value now rests not in reinterpretation, but in preservation.

What Are We Collecting When We Collect Ross?

A Bob Ross painting is not merely a landscape. It’s an artifact of broadcast intimacy. To own one is to hold a piece of the medium’s golden era — a time when television was slow, kind, and one-on-one. It’s to recall a form of attention that now feels endangered. In an age of ultra-fast content and streaming overload, Ross’s analog rhythm offers a different kind of luxury: time, attention, and emotional space.

Collectors of Ross are, in many ways, collecting that emotional ecology. His work does not lend itself to art-historical analysis in the traditional sense. It does not push formal boundaries or interrogate political structures. But it does offer something rare: beauty without cynicism, technique without pretension, and art without intimidation.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As the market for Bob Ross continues to evolve, several possibilities loom. Will museum retrospectives follow? Will Ross’s works find themselves beside canonical figures in American art history exhibitions? Will the demand for his originals be met with resistance from Bob Ross Inc., or will there be a future where the estate and market coexist more fluidly?

What is certain is that the interest in Ross’s work is not a blip. It is part of a larger cultural reconsideration of who gets to be remembered. In a world where value is increasingly tied to emotional authenticity and shared memory, Bob Ross — humble, gentle, and persistent — stands as a new kind of icon: the unlikely master whose greatest work was making others believe they could be artists, too.

Impression

Bob Ross once said, “We don’t make mistakes — we just have happy accidents.” It is perhaps the most quoted phrase in his lexicon, and yet its resonance feels newly profound. The current market emergence of his paintings may seem accidental, but it is anything but. It’s the delayed recognition of a man who never sought celebrity, whose work quietly seeped into the American consciousness, and whose aesthetic now radiates with the warmth of a shared memory.

In the end, to collect Bob Ross is not to chase prestige — it’s to affirm a lineage of emotional truth, to honor the beauty of simplicity, and to remember that even in art, kindness endures. That’s not sentiment. That’s history.

No comments yet.