Few names in modern art are as universally recognized—and deeply personal—as Frida Kahlo. The Mexican painter, known for her emotional self-portraits and unflinching explorations of identity, pain, and politics, has transcended time to become a symbol of creative resistance and self-possession. But what happens when another artist picks up the brush and attempts to paint the painter herself?

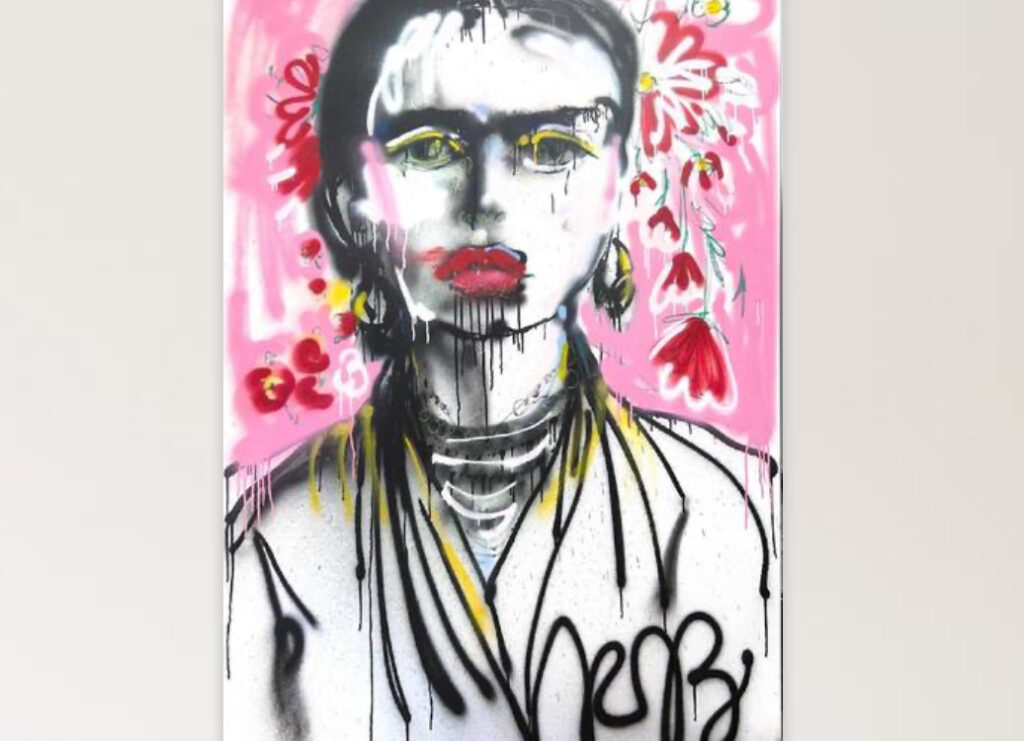

This is the territory Rebecca Russo ventures into with her recent acrylic-on-canvas painting titled simply, Frida Kahlo. More than a likeness, Russo’s piece is an act of translation—one female artist interpreting another across generations, across media, across geography.

Crafted with acrylics and emotion, Russo’s Kahlo is not a replication. It is a resonance, an homage built not just from visual form but from conceptual empathy. In her painting, we see not just Kahlo’s face—but her force.

Medium Matters: Acrylic as a Tool for Modern Myth

Russo’s choice of acrylic is more than technical convenience—it’s symbolic. Acrylics dry fast. They layer with immediacy. They reflect the tension between urgency and permanence. For an artist channeling Kahlo—whose life was a constant tension between motion and constraint—acrylics provide a visceral language.

Where oils would require slow blending, Russo’s brushwork is assertive and layered, matching the cadence of modern identity—fragmented, urgent, collaged. The colors don’t melt—they collide. This is not an artist trying to emulate Kahlo’s palette, but one trying to match her pulse.

The canvas carries its own contradiction: smooth gessoed ground meets dry-brush textures and impasto scars. It feels like both a diary and a protest banner.

Visual Composition: The Anatomy of Reverence

At first glance, the painting presents Kahlo in her iconic frontal gaze: centered, steady, unyielding. But Russo’s version distorts subtly, signaling this is no mere tribute—it is a dialogue.

Eyes and Expression

Russo paints the eyes not in photographic detail but in deliberate stroke clusters—swirls of black, ultramarine, and burnt umber. This abstraction does not distance the viewer; it invites them to look into Kahlo rather than at her. Her pupils glint with a translucent violet, a spectral presence just beneath surface reflection.

The eyebrows—forever one of Kahlo’s most recognizable features—are not fetishized but honored. Russo paints them not as a meme-worthy unibrow but as a bridge, an architectural arc that unites left and right, self and symbol.

The Body, The Frame

In Russo’s rendering, Kahlo is surrounded by more than flora or fauna—though there are nods to them in shadowy outlines. Instead, her backdrop becomes a thematic mural, where anatomical references (vertebrae, hearts, spines) fade in and out of view. It recalls Kahlo’s own pieces like The Broken Column, where the body was both narrative and battlefield.

Gold leafing and crimson ink mark the corners—suggesting saintly framing, votive painting, or ex-voto energy. Kahlo is framed not as martyr, but as monument.

Symbolism and Subversion

What makes Russo’s painting remarkable is how it doesn’t reduce Kahlo to her most familiar iconography. There is no overemphasis on the flower crown, no parrots or monkeys as props. Instead, Russo leans into psychic symbolism—the kind that animates Kahlo’s work without plagiarizing it.

In the upper-right quadrant, a half-open window floats behind Kahlo’s left shoulder, rendered in loose teal pigment. It seems to offer escape or intrusion—a reference to the viewer’s own gaze.

To the lower left, a severed braid rests delicately against the hem of Kahlo’s blouse, recalling both Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair and broader feminist themes around bodily autonomy and defiance of beauty codes.

The background fluctuates between indigo and scarlet, evoking not place but mood. Russo gives us the psychological terrain of Kahlo’s mind, not the geographic one.

Intergenerational Feminism: A Tribute Without Imitation

In a time where many contemporary tributes veer toward commodification or pop reduction, Russo’s work feels deeply respectful and intellectually generous. She does not costume Kahlo in nostalgia. She confronts her presence as one artist to another.

Russo, herself a multidisciplinary painter and gender theorist, understands the stakes of painting Kahlo. The work is not simply about admiration; it is about activation. Russo brings Kahlo into the present not as decoration, but as a political interlocutor. This painting is not about remembering Kahlo—it’s about letting her speak again.

Feminist Art in the 21st Century: Beyond the Selfie

Kahlo has often been called the mother of the selfie. Her self-portraits were radical acts of self-ownership. But Russo’s work questions the easy parallels between Frida’s work and modern self-obsession. In Frida Kahlo, Russo shows us that self-portraiture is not just about documenting the self—it’s about constructing myth, resisting erasure, and reclaiming authorship.

Here, the “Frida” depicted is more than muse. She is an archive. A protest. A saint of resistance. Russo does not aestheticize Kahlo’s pain, but instead sits with it, amplifies it, and refracts it.

Cultural Reverberations: From Mexico City to Everywhere

Kahlo’s legacy is global. Her face graces t-shirts, tattoos, murals, and memes. But her essence—her rawness, her rage, her creative stubbornness—often gets diluted. Russo’s painting restores that essence.

Though Russo herself is based in Europe, her interpretation resists Western flattening. She does not co-opt Kahlo’s Mexican heritage. Instead, she engages with it through symbolic language and interpretive care.

There are echoes of Mesoamerican motifs in Russo’s linework—spirals, serpents, suns. But nothing is decorative. Every symbol is weighted, every detail earned.

Reception and Critical Response

Since debuting in an intimate group show at the Spazio Non Comune gallery in Milan, Russo’s Frida Kahlo has drawn quiet acclaim. Critics describe it as “visceral homage” and “a portrait that breathes.” Scholars from feminist art collectives have praised Russo’s restraint: “She doesn’t perform Kahlo. She channels her tensions.”

Social media reception has also been respectful, a rarity for work invoking Kahlo’s image. Where many reworkings fall into cliché or aesthetic appropriation, Russo’s painting invites viewers into a deeper dialogue.

Art educator Talia Mendoza wrote in her review, “Russo’s Kahlo doesn’t stare at us. She questions us—asks what we’ve done with her rage, her tenderness, her politics.”

Impression

Rebecca Russo’s Frida Kahlo is not just a portrait. It is a mirror within a mirror, a painting that doesn’t resolve so much as it lingers. In capturing Kahlo, Russo has done something rare: she has painted not just the woman or the icon, but the phenomenon—that force of pain and poise that Kahlo turned into a visual language of survival.

This painting reminds us that to depict an artist is to wrestle with more than face or fame. It is to stand in her questions, to walk her metaphors, to feel the friction of her legacy under the skin.

No comments yet.