There are paintings that tantalize the senses, and then there are those that lodge themselves in cultural memory with the tenacity of a sweet tooth. Wayne Thiebaud’s Pie a la Mode is one such image — a deceptively simple still life that has become a cornerstone of 20th-century American art. For the first time since it debuted over sixty years ago, the painting is heading to auction, emerging from a private collection to reassert its place in the canon of American Pop.

Created in 1962 and featured in the groundbreaking “New Painting of Common Objects” exhibition — the first institutional recognition of Pop art in the United States — Pie a la Mode captures Thiebaud’s signature tension between nostalgia and formal precision. More than just a rendering of dessert, the work is a reflection of America’s postwar psyche, indulgent and lonely, mass-produced and hand-painted. It is, in its own quiet way, a slice of American history.

Now, as it prepares to cross the block at Sotheby’s New York this spring, Pie a la Mode is poised to generate not just seven-figure bidding, but a reevaluation of Thiebaud’s complex relationship to Pop — one that transcended Warholian repetition and instead leaned into affection, subtlety, and brushwork.

THE TASTE OF PAINT

Thiebaud never liked the label “Pop artist.” He saw himself more as a painter’s painter — a student of Morandi, Cézanne, and Matisse. And yet, by the early 1960s, his paintings of cakes, pies, gumball machines, and hot dogs found themselves aligned with the zeitgeist of American consumerism. What set Thiebaud apart, however, was his technique. Pie a la Mode, with its thick impasto frosting, tilted plate, and backdrop stretching like a sundial, is less about commentary and more about care. Each stroke is deliberate. Each highlight is a choice.

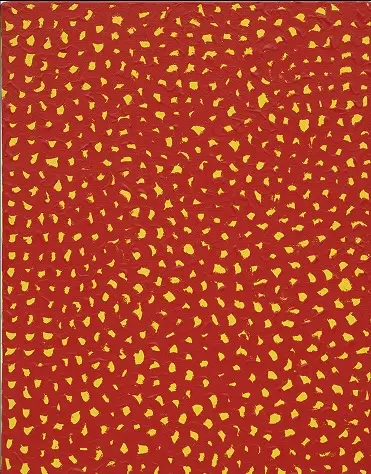

In this 1962 painting, the titular pie — a pale slice topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream — rests on a white dish, centered against a vibrantly colored ground. The composition is stark, the brushwork textured and luminous. The light source is unmistakable, casting angular shadows that give the pie a monumental quality, almost as if it were a modernist sculpture. There is something devotional in Thiebaud’s approach — not religious, but reverent. He gives the pie the dignity of a portrait sitter.

Thiebaud’s sonorous colors and tactile paint application imbue the work with both charm and formality. This is where Thiebaud deviates from his Pop contemporaries. While Lichtenstein flattened and Warhol silkscreened, Thiebaud sculpted with pigment. His pies don’t just look edible; they feel constructed. The brushstrokes are visible, and so is the affection. Pie a la Mode is not ironic. It is sincere.

AN EXHIBITION THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

When Pie a la Mode appeared in the 1962 “New Painting of Common Objects” exhibition at the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum), the show marked a seismic shift in American art. Alongside works by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, and Jim Dine, Thiebaud’s contribution stood out for its warmth. Curated by Walter Hopps, the show was one of the first institutional validations of a movement that was just beginning to coalesce.

But where others in the exhibition deployed brashness or satire, Thiebaud’s offerings — including Pie a la Mode — radiated a quieter kind of inquiry. They asked not just what we consume, but why we love what we consume. His desserts weren’t mass-produced images, but lovingly painted tributes. He once remarked, “I’m interested in the way we isolate objects — put them on pedestals, give them importance.” And that’s what Pie a la Mode does. It isolates a simple American dessert and turns it into a meditation on desire, memory, and domesticity.

At the time of the exhibition, Thiebaud was still teaching at the University of California, Davis, a position he would hold for over four decades. He had worked as a commercial artist in the 1950s, designing advertisements and learning the visual language of persuasion. But in his fine art, he subverted that language. He painted desserts not to sell them, but to consider them. This fusion of commercial imagery and painterly rigor made Pie a la Mode not only a standout of the 1962 show but a lasting icon of American visual culture.

SIX DECADES OFF THE WALL

Since that momentous exhibition, Pie a la Mode has been held in a private collection, unseen by the public for more than sixty years. Its reemergence now is more than a headline-worthy event; it is a cultural excavation. In the intervening decades, Thiebaud’s reputation has only grown. He is no longer seen as a marginal Pop figure but as a vital bridge between midcentury modernism and contemporary figuration.

The auction house has conservatively estimated the painting to sell for between $10 million and $15 million, though it could easily surpass that figure given Thiebaud’s recent market performance and the painting’s pristine provenance. In 2020, his Four Pinball Machines sold for $19.1 million at Christie’s. What Pie a la Mode offers, however, is not just market value, but symbolic weight. It is a foundational work, one that helped define a new chapter in American painting.

Its thick paint still gleams. Its plate still glows. And that quiet melancholy — the kind that always hovered just behind Thiebaud’s cheerfulness — still lingers. The painting is not just a depiction of a dessert. It is a meditation on time, aging, and the rituals we cling to in order to feel whole.

THE AMERICAN STILL LIFE, REIMAGINED

What makes Pie a la Mode so significant is how it reinvigorates the still life. In the hands of the Dutch Golden Age painters, still lifes were symbolic vanitas — reminders of mortality, decay, and the fleeting nature of pleasure. Thiebaud retains that lineage but strips it of overt morbidity. His pies and pastries don’t rot. They persist, eternal and untouched, like plastic fruit in a display case or childhood memories in the mind’s eye.

Yet beneath the sugar lies an ache. In Pie a la Mode, there’s a sense of solitude. The slice sits alone. There’s no fork, no hand, no mouth to receive it. The treat, for all its abundance, becomes a monument to absence. This is where Thiebaud transcends mere aesthetic delight and touches the poetic. He paints pleasure, but also the distance from it. His work recognizes that American optimism often walks hand-in-hand with American loneliness.

This emotional duality — pleasure and distance, nostalgia and alienation — makes Pie a la Mode more than just Pop. It is a psychological painting. A painting of memory.

BEYOND POP: A PAINTER’S LEGACY

In the years since that 1962 debut, Thiebaud’s work has been celebrated globally. Retrospectives at the Whitney, SFMOMA, and the National Gallery have reassessed his oeuvre, revealing the depth and diversity of his themes — from Sacramento cityscapes to vertiginous streets to clowns, dancers, and riverbanks.

But it is his food paintings that remain the most emblematic. They are not gimmicks, but gateways. Through them, Thiebaud explored light, repetition, geometry, and emotion. He once said, “You have to be critical of your work, but never lose the joy.” Pie a la Mode is the embodiment of that mantra: formally exacting, yet full of joy.

And as it prepares for its first public viewing in over half a century, the painting is more than ready to speak again — to collectors, to scholars, to those who remember the 1960s and those discovering Thiebaud for the first time.

This is more than an auction. It is a homecoming.

A FINAL SLICE

In the pantheon of American art, Pie a la Mode holds a curious and powerful place. It’s not grand like a Pollock, nor cerebral like a Johns. But it is unforgettable. It doesn’t shout. It lingers. It invites.

And as the gavel falls at Sotheby’s and the painting passes into new hands, it will carry with it sixty years of silence, longing, and sweetness. A testament not just to Wayne Thiebaud’s skill as a painter, but to his vision of what art — even a painting of pie — can be.

No comments yet.