At 79 years old, David Lynch remains one of the most enigmatic and prolific creatives in modern cinema. He is the rare director whose name has become synonymous with an entire aesthetic: eerie Americana, surrealist dream logic, and the persistent hum of existential dread. From Eraserhead (1977) to Blue Velvet (1986) to Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), Lynch’s films are as much meditations as they are narratives—so it’s fitting that meditation itself lies at the heart of his personal and professional life.

Since 1973, Lynch has practiced Transcendental Meditation (TM) daily—twice a day, every day, without fail. He refers to it not as a spiritual choice but as a practical necessity. “I’ve been meditating for 51 years,” he says, “and it’s brought nothing but light.” But for a man so aligned with metaphysical clarity, Lynch’s life contains contradictions—chief among them his decades-long dependence on tobacco, a habit that has now left him battling emphysema and largely confined to his Los Angeles home.

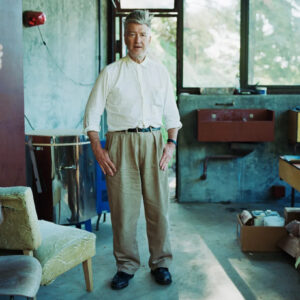

Yet, as ever, Lynch defies simplification. His message isn’t about perfection—it’s about persistence. This is a portrait of a man who smokes, breathes through oxygen tubes, and still meditates twice a day. A man who teaches inner peace to traumatized children while reflecting on his own self-destructive tendencies with brutal candor. A man for whom the act of creating is as involuntary as breathing—no matter how labored the breath may become.

A Practice of Stillness: 51 Years of Transcendental Meditation

David Lynch first learned TM in 1973 after being introduced to it by his sister. At the time, he was a young filmmaker working on Eraserhead—a film that would later gain cult status as a surrealist masterpiece. But his inner life, he admits, was chaotic. “I was filled with anger, fear, and confusion. I’d wake up with dread in my heart,” Lynch recalls.

Transcendental Meditation, a technique developed by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, involves silently repeating a personal mantra for 20 minutes, twice a day. It doesn’t require effort or concentration—it invites transcendence, or what Lynch calls the “purest level of consciousness.”

“You sit comfortably, you close your eyes, and you dive in,” he says. “The deeper you go, the more you connect to that unified field—pure being. That’s where the ideas are.”

For Lynch, TM isn’t just wellness—it’s creative fuel. He likens ideas to fish: “You don’t make the fish—you catch them. But you can’t catch them in a shallow, agitated pond. You need still water.” TM, he says, “calms the surface so the big fish can rise.”

This metaphor has guided his career. During the making of Blue Velvet, Lynch maintained his meditation schedule even while navigating studio interference and financial pressures. On the set of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, he famously insisted on a quiet room for his daily session—even as chaos swirled outside the soundstage.

Scientific Validation: What TM Does to the Brain

Though Lynch’s language is poetic, recent science supports his claims. Studies from Harvard Medical School, UCLA, and the Maharishi International University show that long-term TM practitioners exhibit:

- Increased gamma wave activity in the prefrontal cortex (linked to insight and problem-solving)

- Lowered cortisol levels, meaning reduced stress responses

- Improved connectivity between the left and right hemispheres of the brain

A 2024 Nature study found that TM can even reverse certain biomarkers associated with cognitive decline. For creatives, this means more than just calm—it may mean longer creative longevity.

“You don’t have to be a mystic,” Lynch says. “You just have to close your eyes and do it. Twice a day. Watch what happens.”

The David Lynch Foundation: A Social Experiment in Stillness

In 2005, Lynch founded the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace. Its mission is to provide TM training to vulnerable populations: war veterans, victims of domestic violence, prisoners, and schoolchildren in underserved areas.

To date, the foundation has helped over 1 million children worldwide learn to meditate.

“TM is like a flak jacket for stress,” Lynch explains. “Kids growing up in violent homes or neighborhoods—they’re absorbing trauma all the time. But when they meditate, they start to feel some bliss. That bliss grows. Then negativity flees.”

The results are measurable. In a Chicago high school where TM was introduced, suspension rates fell by 79%. Teachers reported fewer behavioral issues, higher concentration, and improved emotional regulation.

In Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall, inmates trained in TM showed improved impulse control and lower recidivism after release.

The Contradiction: Tobacco, Emphysema, and Creative Fire

Despite his radiant energy and calm, Lynch carries one deeply human contradiction: a lifelong addiction to smoking.

“Cigarettes are beautiful,” he says. “Lighting one, that moment before the first puff—it’s like the beginning of a story.”

Lynch began smoking at 20 and maintained a pack-a-day habit for decades. “There’s something cinematic about smoking,” he explains. “It’s part of my process. I’d draw a frame, light a cigarette, and suddenly the whole scene would come to life.”

But the consequences eventually caught up with him. In 2023, he was diagnosed with emphysema, a progressive lung disease. Now on oxygen support, he rarely leaves home and has had to dramatically scale down his physical activity.

“My lungs are shot,” he admits. “Some people smoke forever and live to 95. I wasn’t so lucky.”

Yet there’s no bitterness. No moralizing. “I don’t recommend it. But I don’t regret it,” he says. “We do what we do. Then we deal with what comes.”

TM, in a strange way, has helped him cope with the physical toll. “Meditation clears the fog. Even when the body hurts, the mind can still fly.”

Creativity Without a Body: Making Art While Grounded

Though his condition has limited his physical range, Lynch’s creative output has never waned. At his home studio, he works daily on:

- Large-scale abstract paintings, sold through Kayne Griffin Gallery in Los Angeles, with prices starting at $50,000

- Experimental sound collages and ambient scores, some recorded with composer Angelo Badalamenti before his death

- Short films created entirely through analog techniques and stop-motion

- A new memoir, rumored to be called Catching the Big Fish: Part Two

Every morning, Lynch rises at 6 a.m., meditates, and begins sketching. “There are limitations,” he says. “I can’t run across a set. But I can still build things in my head.”

In 2024, a short film he directed from home—“Dream Box”—premiered at the Venice Film Festival. Created with only a four-person crew and animated entirely in post-production, it was hailed as “hauntingly Lynchian,” proof that creativity, not physical strength, drives the artistic process.

Philosophy of Practice: Show Up, Don’t Force It

Throughout our conversation, one mantra emerges: consistency over force.

“People think you need inspiration to create. Wrong. You need discipline. Meditation builds that muscle,” Lynch says. “Even if the ideas aren’t flowing, sit there. Every day.”

This discipline extends beyond art. Lynch hasn’t missed a TM session in over five decades. Not during deadlines. Not during illness. Not even on set.

He likens it to brushing your teeth: “You don’t skip because you’re tired. You do it because it makes everything better.”

His approach to life? Equally simple:

- Don’t resist what is.

- Accept what comes.

- Look for the light in the darkness.

“You can meditate on a gurney,” he smiles. “And I probably will.”

Legacy and the Future: Peace Through Consciousness

When asked what he hopes people remember about him, Lynch doesn’t mention films or awards. Instead, he says:

“I want people to know they can access bliss. That it’s real. And that it’s inside them.”

In 2025, the David Lynch Foundation is expanding its reach through online programs, aiming to train 10 million people in TM by 2030, with a special focus on refugee camps, inner-city schools, and rehabilitation centers.

Lynch’s own legacy may be wrapped in darkness and strangeness—but at its core, it radiates peace.

Dualities in Motion

David Lynch is a man of paradoxes. He is the patron saint of the surreal, and a devoted practitioner of stillness. A champion of peace who once defined cinema through violence. A spiritual guide with a cigarette still sometimes in hand.

But perhaps it’s these contradictions that make him so profoundly human—and so enduringly vital. In his life, as in his films, the message is clear: light and background must coexist. The key is not to deny one, but to find balance through awareness.

No comments yet.