For years, the fantasy of a domestic robot has been as consistent as the hum of a washing machine — tireless machines handling everyday chores while we enjoy leisure or creativity. But while language models can already write essays and recommend dinner recipes, robots are still struggling with the mundane.

Folding laundry, for instance, remains one of the hardest problems in robotics. It looks simple until you try to teach a robot to do it. Every wrinkle, every corner, every unpredictable stretch of cotton is a miniature physics puzzle. Which is why, in a quietly strange twist, AI companies are now paying humans to film themselves folding laundry — hundreds of people worldwide performing household chores in front of cameras so robots can learn from them.

It’s digital domesticity at scale. The irony, of course, is that we may never see a robot get tangled in a fitted sheet — that perfect symbol of everyday frustration and imperfection. The modern robot may learn every efficient movement except that one.

The Rise of Chore Data

AI learns by watching. Large language models like ChatGPT are trained on words; robots must be trained on motion, touch, and space. That means video, lots of it.

Companies such as Encord, Micro1, and Scale AI have begun hiring participants to record themselves performing chores — folding towels, loading dishwashers, tidying bedrooms, sweeping floors. Each action becomes data: frames, coordinates, depth maps, and tactile reference. The goal is to create “embodied datasets” that teach robots how to move like us.

Participants might earn $25–$100 per hour depending on the complexity of the task. For the companies, this footage becomes training gold — thousands of gestures that teach models how to predict, grasp, lift, and fold. It’s the robotic equivalent of learning manners by observation.

But there’s a strange poetry in it: people are doing manual labor to teach machines to do the same manual labor for them. It’s a recursive loop of work teaching work — meta-labor, in service of automation.

Folding Laundry: The Impossible Simple

Laundry folding looks trivial. To a robot, it’s chaos.

A towel or shirt isn’t a rigid shape but a deformable one, with infinite configurations and hidden corners. The robot must identify edges, predict how the cloth will move when touched, and adjust its grip to avoid slipping or twisting. One wrong tug, and the fabric bunches up into an irrecoverable mess.

Research groups at Carnegie Mellon University and Stanford have been tackling this for years. Their experiments often involve sophisticated camera systems and tactile sensors that can feel pressure, friction, and the number of layers being held. One breakthrough, the ReSkin tactile sensor, can tell if a robot has grabbed one layer or several. It’s the equivalent of knowing either you’ve accidentally picked up both your shirt and the undershirt clinging to it.

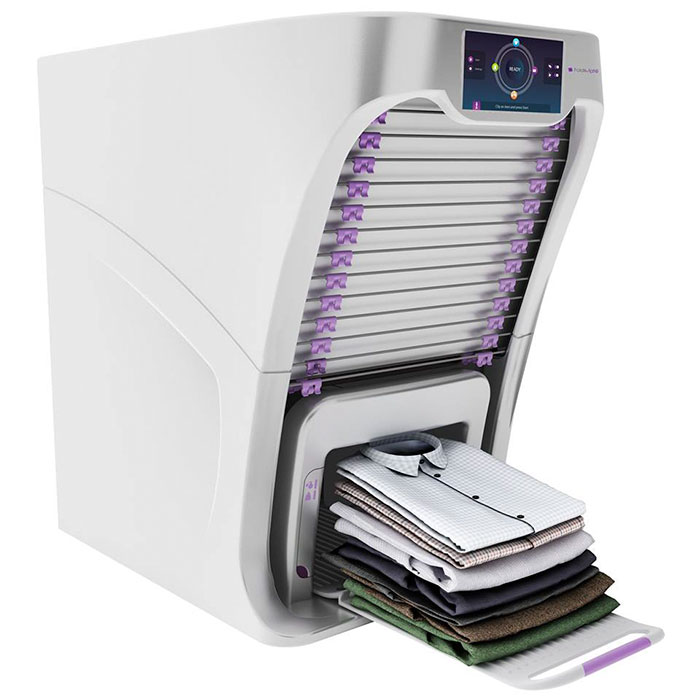

Then there are robots like SpeedFolding and SSFold, designed specifically to learn from human demonstration. In controlled environments, these systems can fold up to 40 items per hour with 90–99% accuracy — better than most teens, perhaps, but still far from household-ready.

And yet, the same systems freeze when faced with chaos: a tangled duvet cover, a wrinkled hoodie, a fitted sheet. The elastic edges defy geometry. The folds are non-repeatable. The problem isn’t just control; it’s comprehension. Robots excel at precision, not improvisation.

The Missing Chaos

This is where the disappointment sets in.

When we say we’ll “never see a robot get tangled in a fitted sheet,” it’s not just a joke — it’s a critique of how we design technology. Every training dataset is curated to remove error, to emphasize success. Robots learn from perfect folds, perfect lighting, perfect gestures. The messy folds, the lazy corners, the accidental drags — all filtered out.

But those imperfections are the texture of real life. They are the moments that make the act human. Folding laundry isn’t just physics; it’s ritual, memory, distraction, frustration, even meditation. It’s the smell of detergent, the satisfaction of smooth cotton, the small triumph of matching socks.

If robots are only trained on idealized data, they’ll never understand — or even mimic — the full poetry of the task. They’ll perform domesticity, not participate in it.

Labor About Labor

This quiet wave of chore-filming also opens a deeper conversation about labor ethics.

In theory, automation frees people from drudgery. In practice, it often means paying people in the short term to create the datasets that make their labor redundant in the long term. Folding laundry for AI might feel easy money, but it’s also another layer of invisible work — the hidden foundation of future automation.

And then there’s privacy. Inviting AI companies into your home, to watch you cook or fold or clean, raises questions about surveillance and consent. Whose homes are recorded? Whose bodies? Whose data teaches the robot what “normal” looks like?

Just as early internet datasets reflected certain cultural biases, these domestic datasets might encode class, culture, and aesthetic preferences. The “right” way to fold a towel isn’t universal. If all the training data comes from Silicon Valley households, we may end up with robots optimized for Californian living rooms, not the world’s diverse realities.

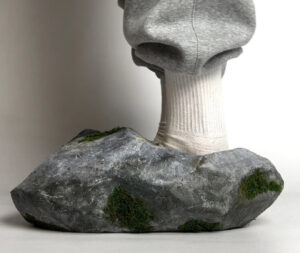

The Fitted Sheet as Philosophy

The fitted sheet — that soft nemesis of domestic life — becomes a symbol here. It resists perfection. No matter how carefully you fold it, one elastic edge always rebels. There’s something comfortingly human in that failure.

Robots will be trained not to fail. Their learning loops will exclude mess, noise, and frustration. But imperfection is a form of personality. The inability to neatly fold a fitted sheet is, in a way, our shared human admission: not everything needs to be optimized.

When engineers say their robots will “never get tangled,” what they really mean is that the system will refuse to try tasks that fall outside its parameters. That’s not intelligence — it’s avoidance. True intelligence might involve getting tangled, learning, retrying, and finding humor in the failure.

Impression

Even if these systems perfect towel folding, scaling up to the full domestic spectrum — from ironing to vacuuming to bed-making — will be a long road. Researchers estimate it may take another decade before general-purpose household robots can perform at human-equivalent skill levels.

In the meantime, we’ll continue to pay people to fold laundry on camera, expanding the dataset one sleeve at a time. The real lesson of this era isn’t about robots replacing us; it’s about how much hidden, repetitive, sensory labor underlies even the simplest human actions.

And when the day comes that a robot can finally fold a fitted sheet, smooth its corners, and place it neatly on a stack — we might feel pride, but also loss. Because somewhere in that seamless motion, a little bit of our imperfection, our everyday struggle, our domestic humanity, will have been quietly ironed out.

No comments yet.