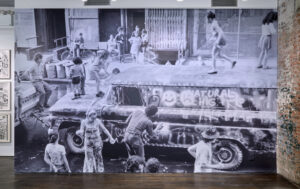

Long before street art made it into auction houses and white-walled galleries, Gordon Matta-Clark staged a quiet revolution—by pointing a camera toward graffiti and asking the art world to look.

On a chilly spring morning in 1973, tucked away inside the bare-bones, artist-run space at 112 Greene Street in SoHo, a handful of onlookers found themselves standing face-to-face with New York City subway cars—printed across long, horizontal photo sheets and overlaid with bursts of saturated, hand-painted color. This wasn’t another Conceptual piece. It wasn’t Minimalism. And it certainly wasn’t “official” graffiti art as the world would come to know it decades later.

This was Alternatives.

And it was unlike anything else showing in New York’s downtown art world at the time.

A Quiet Act of Subversion

To understand the significance of Alternatives, you have to understand the artist behind it. Gordon Matta-Clark—architect, photographer, and provocateur—was never content to leave art within its boundaries. Famous for cutting holes through buildings and challenging the permanence of architecture itself, Matta-Clark had a natural instinct for working at the edges of systems.

In 1972, he turned his attention to graffiti—not the kind sanctioned by galleries, but the kind booming uptown in the Bronx and Harlem, across abandoned walls and subway trains. At a time when graffiti was criminalized, pathologized, and largely invisible to the art establishment, Matta-Clark saw it differently.

Armed with his camera, he began walking the streets, riding trains, and photographing tags, burners, and murals—documenting an emerging language of self-expression that was raw, rhythmic, and deeply political. He took over 2,000 photographs, many of which remain unpublished to this day.

But Matta-Clark wasn’t just archiving. He was interpreting.

Photoglyphs: Painting on Documentation

The photographs themselves weren’t the end result—they were the first step. Back in his studio, Matta-Clark began transforming these black-and-white prints with hand-painted flourishes. Using airbrush techniques and a precise, almost reverent approach, he reintroduced color, energy, and life into the images.

These pieces, which he called Photoglyphs, weren’t attempts to replicate graffiti—they were attempts to learn from it. Like a painter studying a master’s canvas, Matta-Clark seemed to be teaching himself the syntax of this visual dialect: the layering, the letterforms, the aggressive saturation that defied the grime of the city.

He wasn’t co-opting the movement. He was framing it—making it visible to those who would never take the 2 train to the Bronx or walk past a handball court tagged with Taki 183.

112 Greene Street: A Gallery Without Rules

The venue for Alternatives couldn’t have been more fitting. 112 Greene Street was an artist-run space that functioned more like a laboratory than a gallery. Founded by Jeffrey Lew and Gordon Matta-Clark himself in 1970, it gave artists space to experiment, to break rules, to work in ways that commercial galleries simply couldn’t accommodate.

This wasn’t a Chelsea showroom or a MoMA retrospective. It was raw. The floors were unfinished. There were no frames or press releases. Shows were temporary, ideas were in flux, and audiences were small but influential.

At Alternatives, Matta-Clark mounted his Photoglyphs in long horizontal strips. Subway cars became scrolls. Graffiti tags turned into hieroglyphics. The contrast between the flat grayscale of the photo paper and the vivid airbrush color felt electric—especially in an era where Minimalism still held cultural capital and anything “urban” was dismissed as dangerous or juvenile.

Visitors didn’t quite know what they were seeing. Was this photography? Was it painting? Was it graffiti? Matta-Clark’s refusal to define it was the point.

Why “Alternatives” Mattered

In 1973, graffiti wasn’t just unrecognized by the art world—it was demonized. The city was in crisis. Public infrastructure was failing. And young people painting trains were being cast as threats to public order. The very idea of placing graffiti in an art space was considered radical, even reckless.

Matta-Clark, however, saw graffiti as architecture. As semiotic rebellion. As mark-making of the highest cultural significance.

Alternatives offered a counterpoint to dominant art narratives—hence the title. It suggested other ways of making, other spaces of creativity, and other voices that had something vital to say. It was, in every sense, an exhibition about refusal: the refusal to accept hierarchy, the refusal to separate “high” and “low” art, the refusal to ignore what was happening just a few subway stops north.

Bridging Worlds: Downtown Meets Uptown

What made Alternatives so unique wasn’t just the work—it was the gesture. Matta-Clark was using his cultural access to redirect attention. In a time when artists like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt were refining systems, Matta-Clark was exploring disruption.

There’s a strong argument to be made that Alternatives laid early groundwork for later integrations of graffiti into the art world. When Jean-Michel Basquiat began tagging as SAMO in the late ‘70s, or when Keith Haring brought chalk drawings to the subway, they were entering a conversation that Matta-Clark had quietly opened five years prior.

Even more, Alternatives helped shift how documentation was understood in conceptual art. The photos weren’t just evidence—they were transformation. They asked: what happens when the document becomes the artwork?

Legacy: Largely Forgotten, Increasingly Relevant

Despite its significance, Alternatives is rarely discussed in histories of street art or Gordon Matta-Clark’s career. Overshadowed by his architectural “building cuts” and his food-focused work with Food (the artist-run restaurant he co-founded), this exhibition has lived in the footnotes of New York’s art history.

But in recent years, it’s gaining renewed attention.

With the rise of interest in street art, social practice, and anti-institutional aesthetics, Alternatives now looks less like an anomaly and more like a blueprint. It anticipated the breakdown of the gallery wall. It predicted the future of graffiti as both a global movement and a marketable aesthetic. And it did so without ever speaking over the movement it tried to amplify.

Beyond Nostalgia: Lessons from 1973

To revisit Alternatives in 2025 is to see the intersections more clearly than ever:

- Art and Documentation: How do we preserve ephemeral work without freezing its energy?

- Cultural Translation: Who gets to frame someone else’s expression for a new audience?

- Value and Context: What does it mean to place a “vandal’s” work in a gallery space—and who benefits?

Matta-Clark didn’t offer answers. He offered experiments. He made graffiti legible to an audience that might have never acknowledged it otherwise. But he didn’t clean it up. He didn’t steal it. He let it speak.

In that sense, Alternatives wasn’t just a pop-up show. It was a gesture of solidarity.

Looking Back to Look Forward

Today, as street art is commissioned by city governments and auctioned at Sotheby’s, the raw urgency that defined early graffiti risks being polished away. But Alternatives reminds us that this was never just about style. It was about visibility. Resistance. The right to mark one’s presence on an unwelcoming world.

Gordon Matta-Clark, with his camera and airbrush, didn’t make graffiti. But he listened. He saw. He took it seriously.

And in 1973, for just a moment, he built a gallery space where others could see it too.

No comments yet.