Joan Mitchell’s Untitled stands as one of those rare works that bypass language altogether, moving directly into sensation — the kind of painting that doesn’t ask to be decoded so much as it demands to be felt. Coming from the canon-defining era of postwar American art, Mitchell’s work is a reminder that abstraction, at its highest level, becomes a form of autobiography: emotional, environmental, and deeply embodied. As part of American Visionaries: Property from an Important Private Collection, this painting doesn’t merely appear within an auction context — it arrives with the sort of gravity that suggests a private collector who understood the difference between owning art and living with it.

Mitchell, who came of age alongside the titans of Abstract Expressionism, never allowed herself to be defined by the movement’s mythology. While contemporaries often sought grand gestures or existential bravado, Mitchell’s power came from a quieter, more internal place. Her best paintings, including Untitled, radiate an emotional intelligence and an intuitive understanding of color that set her apart then — and make her increasingly vital today.

flow

Mitchell frequently rejected the idea that her work was nonrepresentational. Though she abstracted form with a radical fluency, her visual language was grounded in the memories of landscapes she loved: Chicago childhood summers, the Seine River in Vétheuil, fields and wind and light in constant dialogue. Untitled functions as an interior landscape — a chromatic orchestration in which memory and observation blur until they become indivisible.

The canvas pulses with what can only be described as kinetic stillness. Mitchell’s brushwork always carries motion, but it is the motion of nature — gusts of air, slow passing light, sudden bursts of clarity. Her strokes here hover between aggression and tenderness, the painted marks layering in a rhythm that feels improvisational yet unmistakably deliberate. Mitchell once said she painted to “define a feeling,” and that conviction shapes every inch of the composition. There is no narrative to follow; there is an atmosphere to enter.

idea

Few artists have mastered color with the kind of intensity and nuance that Mitchell possessed. In Untitled, the palette is both sparing and explosive, a hallmark of Mitchell’s late 1950s and early 1960s output. Blues and greens may collide or rest against fields of ochre or white; near-blacks might appear suddenly to anchor the entire composition. These colors do not decorate the painting — they construct it. They serve as the architecture holding the emotional world inside the frame.

Mitchell worked wet-on-wet, often scraping, lifting, and reapplying pigment in ways that created a spatial depth comparable to sculptural relief. The density of certain passages contrasts with areas of raw canvas or thin washes, leading the eye across the surface in a choreography that feels spontaneous but is built from profound discipline. Each color interaction becomes a revelation, as if the painting is still forming itself in real time.

stir

Where some Abstract Expressionists approached gesture as a performance — something that translated physicality directly onto the canvas — Mitchell rejected theatrics. Her marks are deeply personal, unshowy but fiercely intentional. The authority of her gesture comes from its honesty, its refusal to pretend, its ability to express vulnerability without fragility.

In Untitled, the gestures act as emotional timestamps. A vertical slash may echo tension; a luminous flick of pigment may feel like release; a cluster of overlapping strokes might suggest a moment of remembering something too complex or too intimate for words. Mitchell doesn’t describe emotion — she enacts it. The painting becomes a portrait not of a place or a moment, but of Mitchell’s internal esteem.

fwd

Mitchell’s legacy has undergone a significant transformation in recent decades, partly because the art world has finally begun reckoning with the male-centered structures that long overshadowed female Abstract Expressionists. While her work was respected during her lifetime, she was often contextualized as an outlier or a postscript to the movement rather than a central force within it.

Today, she is increasingly recognized as a master whose contributions parallel — and in many ways surpass — her more mythologized peers. Paintings like Untitled prove this. They show an artist pushing abstraction not toward chaos or catharsis, but toward clarity, memory, and lived experience. Mitchell’s abstraction is not inscrutable. It is intimate.

sequester

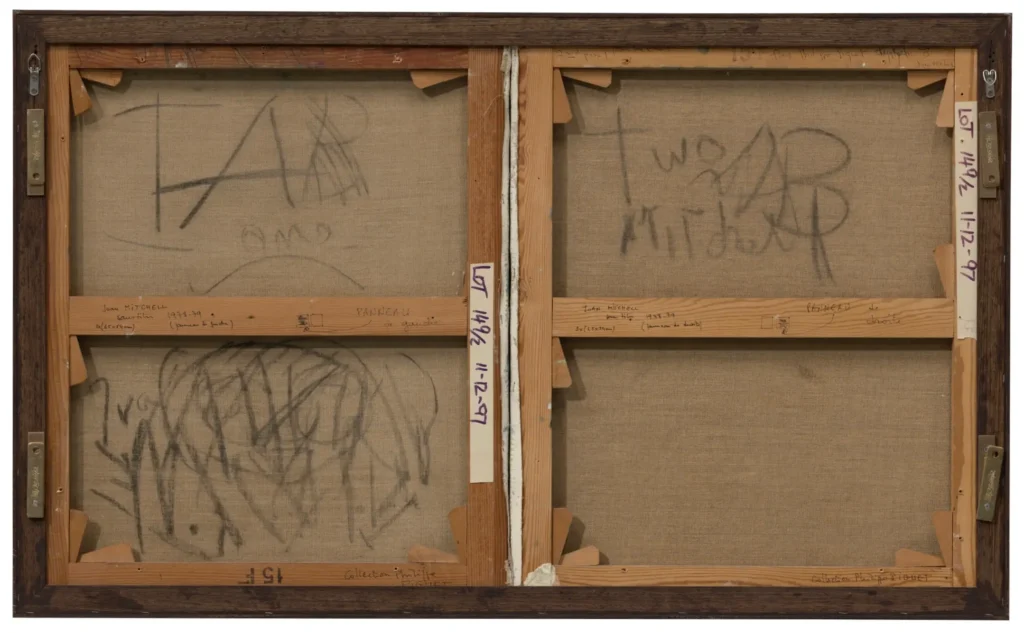

The inclusion of Untitled in American Visionaries: Property from an Important Private Collection gives the work a different kind of resonance. Provenance matters with Mitchell — many of her collectors were early believers, individuals whose connection to her paintings often bordered on the personal. Works that stayed in private hands for decades tend to carry an aura of uninterrupted care, and they often reveal the painter’s quieter, more exploratory modes.

A privately held Mitchell painting, especially one titled simply Untitled, usually indicates a work the collector lived with daily: not a statement piece for show, but a companion. It reflects the kind of collecting that values intimacy over spectacle, depth over trend. Bringing such a work into public visibility reframes it — not as a commodity, but as a cultural artifact from someone who recognized Mitchell’s genius long before the broader market recalibrated.

show

In the current moment, Mitchell’s work feels more urgent than ever. There is a renewed cultural appetite for art that trusts emotion over theory, sensation over explanation. Younger painters, particularly those working in abstraction, often cite Mitchell as an essential precedent — not only for her innovations with color and gesture but for her insistence on subjectivity as a valid artistic force.

Untitled reads as remarkably contemporary: its looseness, its refusal to resolve into predictability, its unguarded openness. Mitchell’s language was so ahead of its time that it feels aligned with today’s most progressive aesthetic conversations, from the resurgence of lyrical abstraction to the rediscovery of painterly emotionality.

impression

Ultimately, the power of Joan Mitchell’s Untitled lies in its breath — the sense that the painting is alive, expanding and contracting as the viewer engages with it. Her best works do not sit still on a wall. They shift. They envelope. They confront and console.

To look at Untitled is to enter Mitchell’s space of feeling, one where memory is a physical texture and emotion takes shape in color. It is a painting that resists closure, that leaves room for the viewer’s own interior landscape to resonate against Mitchell’s. Within the auction context, it becomes not just a masterpiece of American abstraction, but a testament to a life lived intensely, observed deeply, and translated onto canvas with uncompromising honesty.

In a market increasingly saturated with spectacle, Mitchell’s Untitled reminds us that true vision is not loud — it is luminous.

No comments yet.