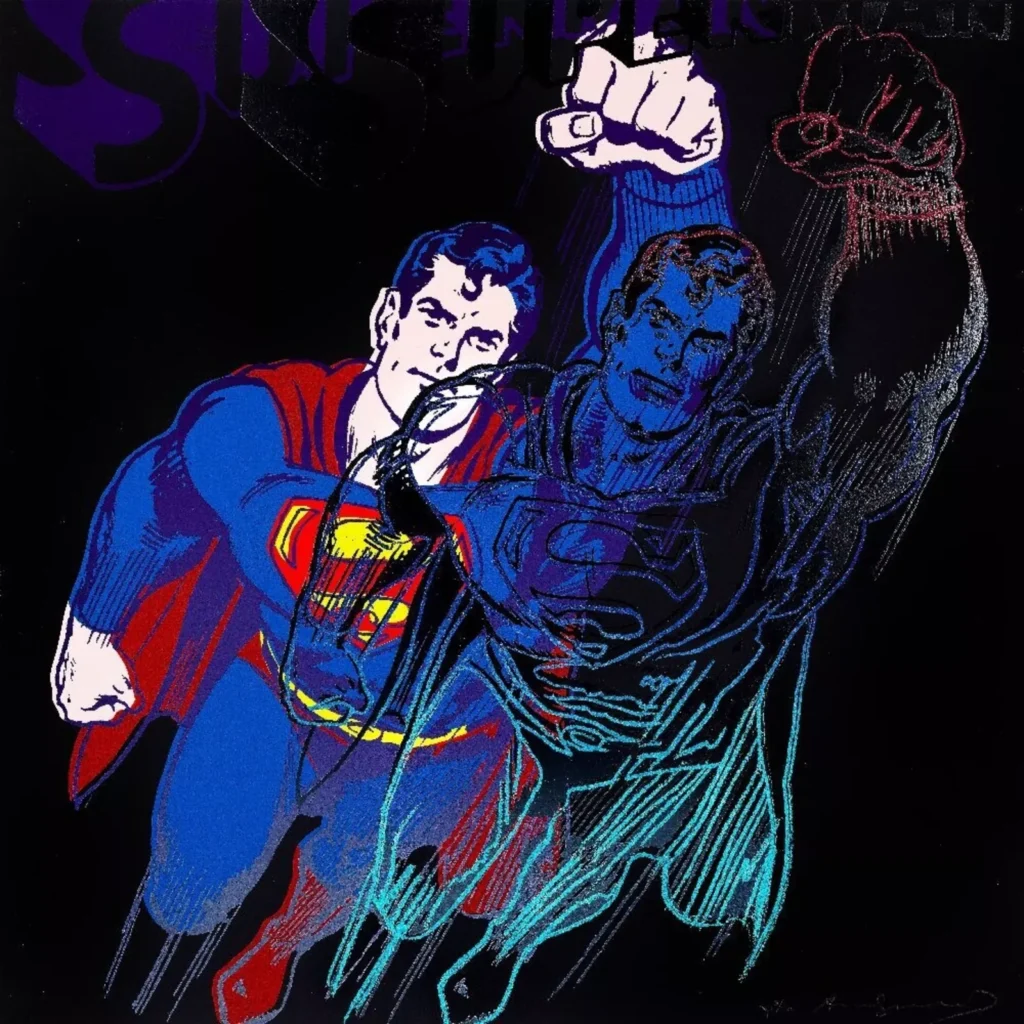

When Andy Warhol created Superman in 1981 as part of his celebrated Myths portfolio, he was not simply representing a pop-culture icon; he was diagnosing the American psyche. The superhero was no longer a comic-book fantasy confined to drugstore racks and childhood bedrooms. By the 1980s, Superman had already crossed into the cultural bloodstream—part morality tale, part capitalist mascot, part secular deity. Warhol saw in Superman what he had long recognized in Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Elizabeth Taylor: an image so deeply saturated in public consciousness that it had transcended its own origins.

Superman from Myths is thus a portrait not of a character, but of a belief system. Warhol’s diamond-dust execution elevates this effect, coating Superman’s silhouette in a shimmering, celestial aura. The glitter functions not as decoration but as commentary. It highlights the commodification of legend, the spectacle of heroism, the gleaming surface of American optimism. Warhol understood that Superman—like the celebrities he obsessed over—was a mirror that society held up to itself, a mask it wore to hide anxieties, failures, and desires. In this way, Warhol’s Superman is both a celebration and a critique: an image that dazzles its viewer while quietly exposing the machinery of myth.

portfolio

Warhol’s Myths portfolio is often described as a late-career return to form, but this underplays its conceptual weight. At the age of fifty-three, Warhol was no longer the enfant terrible of pop; he was an institution, an oracle of image culture. Yet his fascination with fame, fiction, and mass-produced desire remained as sharp as ever.

In Myths, Warhol assembled an eclectic pantheon of American icons—Mickey Mouse, Dracula, Santa Claus, Uncle Sam, the Wicked Witch, Howdy Doody, and others. Some were fictional, some folkloric, some commercial. Together they formed a taxonomy of American storytelling, mapping the myths that animated, entertained, comforted, and haunted the public imagination throughout the 20th century.

Superman occupies a pivotal position within this group. Where Howdy Doody and Mickey Mouse embody childhood fantasy, and Dracula represents imported Gothic fear, Superman is something uniquely American: a hybrid of science fiction, immigrant narrative, frontier optimism, and Cold War anxiety. He is a figure forged in crisis (created in 1938, on the eve of World War II), who promised salvation through strength, clarity, and moral certainty. Warhol recognized him as a sculpture of American self-perception.

The Myths portfolio, despite its playful façade, is Warhol’s meditation on national identity. The imagery suggests that America’s shared narratives no longer come from religion, literature, or ancient folklore—they come from mass media. Superman, perhaps more than any figure in the portfolio, exemplifies this evolution: a deity manufactured not by scripture but by syndication.

1981

Warhol created Superman during a moment of cultural disillusionment. The late 1970s had left the United States questioning its ideals: Watergate, Vietnam, economic stagflation, and a decline in institutional trust had undermined the heroic self-image the country had projected for decades. Yet popular culture attempted to revive it. Christopher Reeve’s Superman films of 1978 and 1980 had restored the character as a symbol of sincerity, hope, and uncomplicated goodness. He was the antithesis to the cynicism dominating cinema at the time.

Warhol sensed the tension between these forces. His Superman is neither the chiseled heroic figure of classical sculpture nor the boyish innocence of the early comic books. Instead, Warhol’s version absorbs the contradictions of his era: the optimism of the superhero revived on screen and the distrust of heroism that hovered in the national mood. The diamond dust captures this paradox perfectly. The image sparkles, but the shimmer feels fragile, almost brittle. It is a glittering surface stretched over a deeper uncertainty.

Warhol understood that Superman’s appeal in 1981 was not simply nostalgic; it was compensatory. A culture weary from disappointment needed a perfect hero to believe in again. Warhol’s print dramatizes this need, framing Superman not as a symbol of true power but as an icon whose power comes from the desire projected onto him.

the diamond-dust effect

The glittering diamond dust that coats Superman transforms what could have been a flat pop image into something alchemical. Warhol had been experimenting with diamond dust since the late 1970s, fascinated by its ability to elevate commodity imagery into the realm of the sacred. Applied unevenly, the particles catch light unpredictably, giving the surface a living quality—almost breathing, almost glowing.

In Superman, the diamond dust serves several functions. Aesthetically, it mimics the cosmic radiance associated with the character. Superman is not merely terrestrial—he comes from the stars. The glitter becomes a metaphor for extraterrestrial luminescence, embedding the mythology into the materiality of the work.

Conceptually, diamond dust reinforces Warhol’s interest in spectacle. Celebrity, advertising, and fantasy all depend on shine, sparkle, excess—qualities that transform the ordinary into the aspirational. By coating Superman with this shimmering texture, Warhol literalizes the glamour of myth. He knows exactly what he is doing: he is creating a shrine.

Philosophically, the diamond dust hints at the artificiality of heroism. The glitter is seductive but superficial. It dazzles the viewer while concealing the flatness beneath. Warhol’s sparkle is always a trap. It invites the viewer to celebrate the icon while simultaneously provoking them to question why the glimmer is necessary at all.

self-portrait

All of Warhol’s portraits are, in some sense, self-portraits. He once remarked that he wanted to be as plastic, as reproducible, as his celebrity subjects. Superman, with his dual identities—Clark Kent and the Man of Steel—provided Warhol with a potent metaphor for the fragmentation of self that fame requires.

Superman is a character who performs normalcy and hides power. Warhol was an artist who performed detachment and hid insecurity. Both cultivated personas that were as important as their true identities. In this way, Superman becomes an indirect autobiographical statement.

Warhol’s world was filled with contradictions: public fascination and private loneliness, mass visibility and personal opacity, financial success and emotional fragility. Superman encapsulated these tensions perfectly. The superhero is beloved yet isolated, powerful yet vulnerable, adored yet misunderstood. Warhol saw himself in this paradox.

Even the print’s palette—its saturated reds and electric blues—echoes Warhol’s contradictory relationship with American culture. The colors are patriotic but synthetic, bold but mechanical. They reflect his immersion in American consumerism and his simultaneous detachment from it.

flow

Warhol understood that myths are not born; they are manufactured. And in the United States, they are often manufactured for sale. Superman was, from the beginning, both hero and product—printed, distributed, licensed, merchandized, franchised. He was a dream you could buy at the supermarket.

Warhol’s Superman makes this dynamic visible. The heavy black outlines and flat planes of color recall mass printing techniques. The simplified composition foregrounds reproduction over originality. The diamond dust, more than mere decoration, acts like a luxury upgrade—Superman as haute commodity.

In essence, Warhol shows that myth in America is indistinguishable from branding. The superhero’s “S” emblem is not just a symbol of strength—it is a logo. Warhol knew logos better than anyone. They were modern hieroglyphs. They told a story the way ancient myths once did.

By placing Superman in the Myths portfolio, Warhol equates him with figures like Santa Claus and Uncle Sam—characters who operate simultaneously as cultural myths and commercial engines. This is not a critique. It is a fact. Warhol does not condemn consumerism; he reveals it as the architecture of belief in modern life.

the superhero as secular savior

Superman’s origin story—alien child sent to Earth, raised by ordinary parents, possessing extraordinary powers—echoes religious narratives. He is part Moses, part Christ, part American frontier archetype. Warhol, raised Catholic and fascinated by icons, understood the overlap between religious imagery and pop imagery.

The diamond-dust surface functions like a halo. The bold posture mimics the stillness of saints in Gothic altarpieces. Yet the spirituality is mediated through modern mass culture. Warhol transforms the superhero into a secular icon of hope. But the irony is subtle: Superman promises salvation, but only within the boundaries of fiction.

The hero exists to reassure the viewer, to offer certainty in a world of doubt. Warhol’s print reveals the fragility of this reassurance. The shimmer may dazzle, but it is as impermanent as glitter caught in light. The savior is made of ink and dust.

leg

Today, Warhol’s Superman stands as one of the defining images of late pop art. Its relevance has only increased. In an era dominated by superhero blockbusters, brand loyalty, and corporate myth-making, Warhol’s vision feels prophetic. He understood long before the 21st century that myth and media would merge into a single cultural force.

The print continues to be highly sought after in the auction world precisely because it captures this shift. It is an artifact of early Reagan-era optimism, yet it speaks fluently to current anxieties about identity, power, spectacle, and belief.

More than that, the work remains emotionally resonant. Underneath the sparkle and irony is a yearning for guidance, for clarity, for a hero who might actually exist. Warhol’s Superman is not cynical—it is wistful. It acknowledges our need for myths while gently revealing the mechanisms that make them.

impression

Andy Warhol’s Superman, from the Myths portfolio, is far more than a pop appropriation. It is a psychological portrait of America’s imagination. It is a glittering critique of heroism, a meditation on fame, a self-portrait in disguise, and a commentary on the fragile machinery of myth-making.

Warhol invites us to look at Superman not as a savior, but as a mirror. The diamond dust does not merely sparkle; it exposes. It catches light the way myths catch longing. It reflects the viewer’s desires, fears, and fantasies.

In the end, Warhol’s Superman is not about the hero.

It is about the human need to create one.

No comments yet.