When Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio—better known worldwide as Bad Bunny—steps onto the Super Bowl halftime stage, it will not just be another headline-grabbing performance. It will be a cultural milestone. For Puerto Rico, for Latin music, and for the visibility of diasporic identities across mainstream entertainment, Bad Bunny’s presence at the biggest televised spectacle in the United States will carry the weight of history. Super Bowl halftime shows have long been a barometer of pop culture power, but they have rarely centered voices that emerge from outside the American pop mainstream. In giving the stage to a Puerto Rican reggaeton and Latin trap artist, the NFL is tacitly acknowledging the global influence of Latin music—and the particular resonance of Puerto Rico’s story.

Puerto Rico on the Global Stage

Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States is complicated. It is an unincorporated territory, simultaneously bound to American political structures yet often marginalized within them. Culturally, however, Puerto Rico has always punched above its weight. Salsa, reggaeton, bomba, and plena all emerged from the island as expressions of colonial history, resistance, and joy. Its athletes—from Roberto Clemente to Monica Puig—have claimed international prestige. Yet mainstream platforms like the Super Bowl have often overlooked Puerto Rican identity, instead filtering “Latin” culture into generalized, homogenized aesthetics.

That changed slightly in 2020, when Jennifer Lopez and Shakira co-headlined a Miami halftime show that foregrounded Latin identity with salsa interludes, reggaeton rhythms, and explicit political symbolism, including children in cages references and Puerto Rican imagery. But Lopez and Shakira were global icons long before their halftime turn, representing the Latin diaspora at large more than Puerto Rico specifically. Bad Bunny, by contrast, wears his island identity like a badge. He sings in Spanish unapologetically, he references Puerto Rican slang, and he consistently pushes for political awareness of the island’s struggles with colonialism, debt crisis, and natural disasters.

To see Bad Bunny headline a Super Bowl show is therefore to see Puerto Rico claim the center of an American cultural ritual that has historically sidelined it.

Bad Bunny’s Rise: From SoundCloud to Stadiums

Bad Bunny’s ascent reads like a parable for the democratization of global music. From uploading tracks on SoundCloud in 2016 to becoming Spotify’s most-streamed artist globally for three consecutive years (2020–2022), he has defied the rules of language, geography, and genre. His collaborations with Drake, Cardi B, Rosalía, and even WWE brought him to audiences beyond Latin America, yet he has refused to compromise his identity: he still primarily records in Spanish, still raps in Puerto Rican cadences, still centers island references in his videos.

His stadium tours, particularly El Último Tour del Mundo and World’s Hottest Tour, were not just concerts but cultural phenomena, filling arenas from San Juan to New York to Madrid. Forbes declared him “the biggest pop star on the planet,” a label once unthinkable for a reggaeton artist. The Super Bowl stage is thus not a leap into mainstream recognition—it is the mainstream finally catching up.

The Super Bowl Halftime Show as Cultural Mirror

Historically, the Super Bowl halftime show has been a reflection of dominant cultural narratives. In the 1990s, it leaned heavily on safe, middle-of-the-road pop acts like Gloria Estefan, Michael Jackson, and Diana Ross. The 2000s swung toward classic rock legends—The Rolling Stones, U2, Bruce Springsteen—catering to an older demographic. The 2010s embraced millennial pop: Beyoncé, Bruno Mars, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga.

In the last few years, however, halftime shows have mirrored a shift toward inclusivity and the acknowledgement of cultural diversity. The 2022 performance featuring Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Kendrick Lamar, Mary J. Blige, and Eminem spotlighted hip-hop, a genre long neglected on the NFL’s biggest stage. The 2023 Rihanna show brought a Caribbean-born, Barbadian icon to the forefront. Against this backdrop, Bad Bunny’s show feels like the next logical evolution: not just a Latin cameo within an American narrative, but a full re-centering of the show around Puerto Rican artistry.

Language as Resistance

Perhaps the most radical element of Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance will be his choice of language. Singing in Spanish to an audience of over 100 million viewers in the U.S. alone is a quiet act of resistance. For decades, non-English songs have been relegated to niche radio or “crossover” categories, requiring translation or adaptation to succeed. Bad Bunny’s career proves otherwise. Hits like Dakiti, Tití Me Preguntó, and Safaera charted without English lyrics. His connective channels with mainstream artists rarely involve compromise; instead, he often brings them into his world.

On the Super Bowl stage, his Spanish lyrics will not be a novelty or an afterthought—they will be the core of the performance. This matters because it challenges the dominance of English in American cultural expression. For millions of Spanish-speaking viewers in the U.S. and abroad, it will be a moment of validation. For non-Spanish speakers, it will be an invitation to experience music beyond language.

Symbolism and Puerto Rican Identity

If past Bad Bunny performances are any indication, the halftime show will likely carry overt Puerto Rican symbolism. He has appeared draped in the Puerto Rican flag, worn jerseys referencing island teams, and spoken out against political corruption during concerts. One could imagine a stage design incorporating the island’s colors, references to hurricanes and resilience, or visual nods to reggaeton’s underground club origins.

The timing also matters. Puerto Rico has faced years of economic precarity, political unrest, and climate disasters, from Hurricane Maria in 2017 to ongoing earthquakes and energy grid crises. To see one of its own not just succeed but dominate the Super Bowl stage will resonate as collective healing.

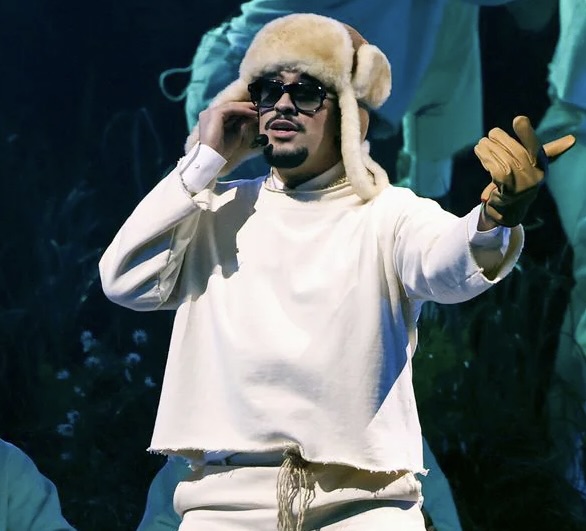

Fashion, Performance, and Theatricality

Bad Bunny is not only a musician—he is a fashion disruptor. From skirts on magazine covers to painted nails and oversized sunglasses, he has shattered Latin masculinity stereotypes. His halftime show will inevitably be as much about visuals as sound. Expect avant-garde styling, gender-fluid costuming, and perhaps collaborations with designers like Jacquemus or Loewe, who have previously embraced his aesthetic.

Theatrically, he thrives on spectacle. Past tours included massive screens, pyrotechnics, and even a full 18-wheeler truck driven into stadiums. The Super Bowl’s production budget will allow him to elevate this to unprecedented heights.

The Diaspora Effect

Puerto Ricans on the U.S. mainland form a vast diaspora community, concentrated in New York, Florida, and beyond. The halftime show will be an emotional flashpoint for them. In the same way Irish Americans rallied around Riverdance in the 1990s or Black Americans celebrated Beyoncé’s homage to HBCUs at Coachella, Puerto Ricans will see in Bad Bunny’s performance a reflection of themselves. This diaspora pride extends globally: Latin audiences from Mexico to Argentina to Spain will feel represented, reinforcing the transnational power of reggaeton.

Flow

The halftime show is also a commercial engine. For artists, it often translates into streaming spikes, album sales, and tour demand. For Puerto Rico, the implications could stretch further. Tourism boards and cultural organizations may leverage the performance to promote the island. Local artists may gain increased exposure, benefiting from the spotlight on Puerto Rican music scenes. Moreover, the show’s success could convince U.S. media industries to invest more heavily in Spanish-language programming, festivals, and crossover projects.

Legacy of the Moment

The true test of Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl show will not be in the fireworks, the choreography, or even the setlist. It will be in its afterlife. Will it inspire young Puerto Rican artists to believe the biggest stage is within reach? Will it encourage future halftime shows to look beyond English-language pop? Will it mark a shift in how Puerto Rico is perceived, not as a periphery but as a cultural center?

History suggests it might. When Beyoncé performed in 2013, she reframed halftime expectations for female performers. When Prince played in the rain in 2007, he redefined what live music could mean on a televised stage. Bad Bunny’s show has the potential to join this canon—not just for artistry, but for cultural representation.

Impression

The Super Bowl halftime show has always been about more than music. It is about spectacle, identity, and cultural politics. For Bad Bunny, it will be the culmination of a journey from a supermarket bagger in Vega Baja to one of the most influential entertainers in the world. For Puerto Rico, it will be a landmark: a moment when its rhythms, struggles, and pride echo across the most-watched broadcast in America.

Whether clad in flamboyant fashion, surrounded by pyrotechnics, or chanting in Spanish to a crowd that might not understand every word, Bad Bunny will make one thing clear: Puerto Rico is not just part of the conversation. It is the conversation. And from this stage, the world will be listening.

No comments yet.