Science fiction has long served as the genre where imagination collides with ideology—where visions of technology, alien life, and dystopian futures reflect back our deepest questions about existence. While the genre spans galaxies of subgenres and tropes, only a select few films have transcended both cinema and culture to become benchmarks not just of sci-fi, but of filmmaking itself. Among these, three masterpieces tower: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Blade Runner (1982), and Alien (1979). Each changed the landscape of cinema. Each redefined how we visualize the future. And each continues to inspire awe decades after their release.

In this review, we journey through the philosophical grandeur of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the noir-drenched cyberpunk of Blade Runner, and the industrial terror of Alien—films that, together, form a holy trinity of science fiction cinema.

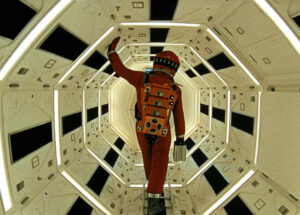

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – Stanley Kubrick’s Celestial Symphony

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is not merely a film—it is a cinematic odyssey, a cosmic meditation, a transcendental puzzle box. Released during the apex of the space race, its ambition dwarfed that of any science fiction film that had come before it. And yet, rather than indulge in rocket-powered nationalism or laser battles, Kubrick delivered something far more cerebral and abstract: a visual essay on evolution, consciousness, and our place in the cosmos.

Written in collaboration with author Arthur C. Clarke, 2001 begins not with space, but with a prehistoric Earth—where a monolith inexplicably appears and catalyzes a leap in hominid intelligence. The jump cut to the orbital ballet of spaceships scored to Strauss’s “The Blue Danube” remains one of the most famous transitions in cinema history, symbolizing humanity’s technological leap from bone tools to space stations.

Every frame of 2001 is a composition, a painting of cool minimalism or sublime terror. The silence of space, the eeriness of HAL 9000’s calm voice, and the surreal stargate sequence transcend narrative and approach pure cinematic experience. HAL, voiced with eerie serenity by Douglas Rain, is not just a malfunctioning AI, but a mirror to human error, paranoia, and the fragility of control. The murderously polite machine ironically exhibits more emotional instability than its human counterparts, prompting questions about the boundary between organic and artificial intelligence.

Yet the film’s greatest gift is its ambiguity. Kubrick eschews exposition in favor of mood and metaphor. The Star Child, the monolith, the enigmatic final act—they all resist literal interpretation, inviting viewers into a contemplative space rarely permitted in blockbuster filmmaking. In 2001, science fiction becomes metaphysics; outer space becomes inner space.

Kubrick predicted flat-screen monitors, voice-activated commands, and commercial space travel. But what he truly foresaw was our thirst for meaning in an era of machinery. In his film, the universe does not answer—it waits.

Blade Runner (1982) – A Dystopian Mirror, Dripping Neon and Rain

If 2001 is a cosmic poem, then Blade Runner is a noir lament—an elegy for humanity drenched in rain, neon, and philosophical despair. Directed by Ridley Scott and based loosely on Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the film envisions Los Angeles in 2019 as a polluted, multicultural megacity teeming with advertisements, decay, and replicants—bioengineered beings designed for labor, now hunted when they rebel.

When it first premiered, Blade Runner was misunderstood. Critics found it slow, dark, and ambiguous. Audiences, expecting Star Wars-style excitement, were alienated by its meditative pacing and bleak tone. Yet over time, aided by various re-edits and director’s cuts, the film has emerged as a foundational work of dystopian fiction—a cinematic text that explores identity, mortality, and memory with haunting precision.

At the center is Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a morally compromised “blade runner” tasked with killing replicants. But it is the replicants—particularly Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer)—who become the film’s emotional and philosophical core. Batty’s final monologue, improvised by Hauer, is a eulogy to experience: “All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.” In that line lies the film’s tragic soul—the replicants, despite being artificially created, exhibit a hunger for life, freedom, and meaning more vividly than the humans hunting them.

Scott’s vision of the future is claustrophobic and tactile. Skyscrapers belch fire. Flying cars drift through acid rain. Cultural detritus and spiritual yearning mingle in alleyways and bazaars. This world feels lived in, aged, and broken—a reflection not only of fears of urban overpopulation and ecological collapse, but of the moral erosion beneath technological progress.

And what of Deckard? Is he human? A replicant? The ambiguity of his identity haunts the narrative and asks the viewer to consider what separates the real from the artificial. Blade Runner is a film of questions, not answers—a mirror more than a story.

Alien (1979) – Terror in the Void

Before Ridley Scott turned Los Angeles into a neon dystopia, he unleashed Alien—a masterpiece of sci-fi horror that taught us space isn’t the final frontier. It’s the ultimate trap.

Released in 1979, Alien inverted the shiny optimism of space adventures. Gone were the clean lines and noble captains of Star Trek—instead we had the Nostromo, a rusty commercial towing vessel crewed by disgruntled workers just trying to make it home. And lurking in the shadows, a creature unlike any other in cinema: the Xenomorph.

At first glance, Alien seems to be a haunted house movie in space. But it’s far more than that. With set designs inspired by Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, the film creates a world that is as biomechanical as it is biological. The Xenomorph’s life cycle—egg, facehugger, chestburster, adult—is an unsettling metaphor for reproduction and violation. The film’s Freudian undertones—phallic intrusions, parasitic gestation—add to its psychological terror.

But Alien isn’t just about gore or monsters. It’s about waiting. Scott’s direction is patient, using sound, silence, and shadows to unnerve the audience. The alien is hidden for most of the film, glimpsed only in fragments—its presence felt more than seen. This absence creates unbearable tension, turning every corner of the Nostromo into a potential death trap.

Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley was a revolution. In an era dominated by male action heroes, Ripley was intelligent, composed, and utterly capable. She didn’t scream—she survived. Weaver’s performance helped pave the way for future female protagonists in genre cinema, from Sarah Connor to Ellen Page.

And let’s not forget the film’s infamous chestburster scene—perhaps the most iconic moment in horror cinema. John Hurt’s convulsing body, the stunned reaction of the crew (largely unscripted), and the alien’s explosive debut remain unforgettable.

Alien made space terrifying. It made blue-collar characters into heroes. And it made us afraid to open mysterious eggs. It wasn’t just a film—it was a transformation of science fiction into horror, grime, and dread.

Bequest: Why These Three Endure

What unites 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, and Alien is not just their brilliance, but their challenge. These are not popcorn films designed for passive consumption. They confront us. They immerse us in unfamiliar futures and force us to reconsider our assumptions.

Each of these films is concerned with what it means to be human:

- In 2001, humanity confronts the unknowable cosmos and its own evolutionary limitations.

- In Blade Runner, humanity is mirrored and questioned by the very machines it creates.

- In Alien, humanity is reduced to survival instincts in the face of an unfeeling, unique organism.

They also share a visual sophistication that has aged like fine wine. The practical effects of 2001 still rival CGI. The cityscapes of Blade Runner remain unmatched in mood. The Xenomorph in Alien is still one of cinema’s most terrifying creatures.

Perhaps most importantly, they all trust the audience. They trust that we can sit in silence, watch backdrops move, and contemplate ambiguity. That’s rare. And that’s why these three films endure.

Reflections from the Stars

There have been many great science fiction films since Alien, Blade Runner, and 2001: A Space Odyssey. But few dare to reach so far inward and outward at once. These films are not only speculative fiction—they are spiritual questions wrapped in steel and starlight.

They imagine the future not as escapism, but as confrontation. What happens when machines outfeel us? When nature turns hostile? When the stars call, but we’re too small to answer?

In answering those questions with silence, poetry, and terror, these three films created new galaxies in our imagination. And as long as stories are told under the night sky, their stars will keep burning.

No comments yet.