In a world saturated with images, Chris Levine doesn’t simply take photographs. He creates portals. A British artist born in 1960, Levine occupies a singular space at the crossroads of photography, installation, performance, music, and meditation. His multidisciplinary oeuvre is built on a single, mesmerizing principle: light as consciousness. Light as presence. Light as perception.

While best known for his iconic portraits of Queen Elizabeth II, particularly Lightness of Being (2004), Levine’s practice extends far beyond royal iconography. His art is not about celebrity, or even about the subjects themselves—it’s about slowing down time. Inviting the viewer to linger. To breathe. To become aware.

The Alchemist of Light

For Levine, light is not just a tool—it is the medium. Unlike traditional photographers who rely on composition, framing, and timing, Levine incorporates laser optics, LED lightboxes, holography, and stereoscopic techniques into his work. His pieces often float in space, pulse with subtle energy, or shimmer at the edge of visibility. They are as much about sensation as they are about sight.

This dedication to light as subject and medium places Levine in an artistic lineage that includes James Turrell, Dan Flavin, and even Olafur Eliasson. But where those artists often work with architectural scale, Levine’s lens remains intimate. He renders people—icons, sages, musicians—not as static images, but as emanations.

Lightness of Being: A Monarch in Meditation

The moment Chris Levine captured Lightness of Being, Queen Elizabeth II was not looking at the camera. She was not posing. She was, for a rare moment, resting.

Commissioned by the Jersey Heritage Trust in 2004 to celebrate the island’s 800-year loyalty to the Crown, Levine was tasked with creating a formal portrait. But during the extended photo session, as he used a custom-built 3D scanning rig to capture her in layers of light, Levine also documented the in-between moments. The unscripted ones. The stillness.

In Lightness of Being, the Queen sits with her eyes closed, her face bathed in soft light, her crown glinting with serenity rather than authority. The image has been hailed as one of the most humanizing portraits of a monarch ever produced. It strips away the ceremonial posture and replaces it with a moment of internal peace—a rare gesture of vulnerability from one of the world’s most scrutinized figures.

Presented in a glowing lightbox, the image becomes a meditation in and of itself. It is not merely a portrait. It is a statement about presence—what it means to be still, to be seen, to simply be.

The Expanded Portrait

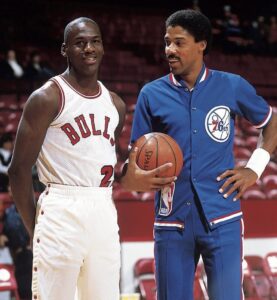

Levine’s work with the Queen isn’t an anomaly. It’s part of a much larger exploration of portraiture as transcendence. Other sitters have included the Dalai Lama, Grace Jones, Banksy, and Kate Moss. Each subject is approached not as a celebrity, but as an energy field—a presence to be translated through light and time.

This process often involves multi-sensory environments, immersive studio setups, and advanced camera rigs. Levine uses time-lapse photography, holography, and stereoscopic 3D imaging to go beyond the surface. He isn’t just documenting what someone looks like. He’s trying to convey how they feel to encounter.

In an age of selfies and surveillance, where identity is flattened into pixels and data points, Levine offers a counter-image: one of depth, aura, and essence.

Meditation as Practice, Not Metaphor

Levine is not interested in metaphor. He is a practitioner of meditation, not just an artist who uses it thematically. His studio routines often begin with silent sitting. His shoots are choreographed around breath. And this is not an affectation. It’s an ethos.

He refers to his art as “a manifestation of a meditative practice,” often quoting the Tibetan principle of the ‘clear light’—the unconditioned awareness that transcends thought. His goal is not just to create visually arresting work, but to use art as a conduit to mindfulness.

The impact on his audience is palpable. Levine’s exhibitions aren’t just viewed—they’re experienced. Viewers often linger for minutes at a time in front of his lightboxes, drawn not by spectacle but by stillness. His work slows the body. Calms the breath. It invites you to stop scrolling.

Sound, Movement, and Collaboration

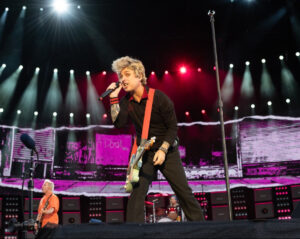

While Levine’s portraits garner the most attention, his installation and performance work pushes the boundaries of what art can be. He’s collaborated with musicians like Philip Glass and Jon Hopkins, created laser soundscapes, and designed immersive chambers of light and vibration.

One notable work, Hypervisual 1.2, combines laser projection, subsonic frequency, and programmed light pulses to create a multi-sensory chamber that induces altered states of perception. Visitors describe the experience as hypnotic—equal parts art installation, sound bath, and spiritual reset.

These projects further cement Levine’s belief that perception is plastic—that through careful control of light and sound, artists can shift how we experience reality itself.

Market Recognition Meets Experiential Intent

Despite the transcendent goals of his practice, Levine’s work has also found a place in the high-end art market. His portraits have been auctioned for six-figure sums, and his limited-edition prints are sought after by collectors around the globe. Yet he remains resistant to commodification.

Each Levine piece is, in his view, “a living work.” Many exist not as static prints, but as light-emitting panels, or as part of immersive installations that defy traditional objecthood. His approach upends art-world conventions: where most collectors look for scarcity, Levine offers immersion; where others seek ownership, Levine offers experience.

That tension—between presence and possession—is part of what gives his work its charge.

Education, Origins, and the Techno-Spiritual Merge

Levine’s journey to light was both artistic and technological. He trained at Chelsea School of Art before earning an MA in computer graphics at Central Saint Martins, placing him among the early wave of digital art pioneers in the UK.

But his work never feels clinical. Instead, it’s shot through with spirituality, emotion, and a sense of the sacred. His background in tech informs his precision, while his meditative ethos infuses it with heart.

That duality—techno-spiritualism—is central to Levine’s importance today. He is not simply bridging disciplines. He is collapsing the gap between the digital and the divine.

The Future: Light as Healing

Looking forward, Levine sees art not just as aesthetic, but as therapeutic. His latest explorations focus on light frequency, biofeedback, and the use of photonic environments for healing trauma and anxiety.

In a post-pandemic world grappling with overstimulation, chronic stress, and digital fatigue, Levine’s approach feels prophetic. His work offers not escape, but entrance—into the body, the breath, the now.

He envisions a world where galleries become sanctuaries, and where art is not consumed but inhabited. A world where light is not only a medium, but a medicine.

Final Word: Slowness as Rebellion

In many ways, Chris Levine is a cultural anomaly. In an era that rewards speed, saturation, and spectacle, he champions slowness, subtlety, and silence. His work resists the noise. It invites you to look longer, to feel deeper, to return to presence.

Lightness of Being may be his most famous work, but it is also a metaphor for his entire practice—a search for that quiet moment between moments, when the world pauses, the eyes close, and something transcendent shines through.

In the kingdom of attention, Levine isn’t a jester. He’s a monk. And his work is not a product. It’s a practice.

No comments yet.