film

To discuss David Lynch purely as a filmmaker is to misunderstand the foundation of his creative identity. Long before Eraserhead reshaped independent cinema, Lynch trained as a painter, studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and immersing himself in the material language of pigments, stains, and surfaces. Throughout his career, he has insisted that cinema is merely one branch of a much larger artistic ecosystem—one that includes drawing, painting, sculpture, music, sound design, photography, and printmaking.

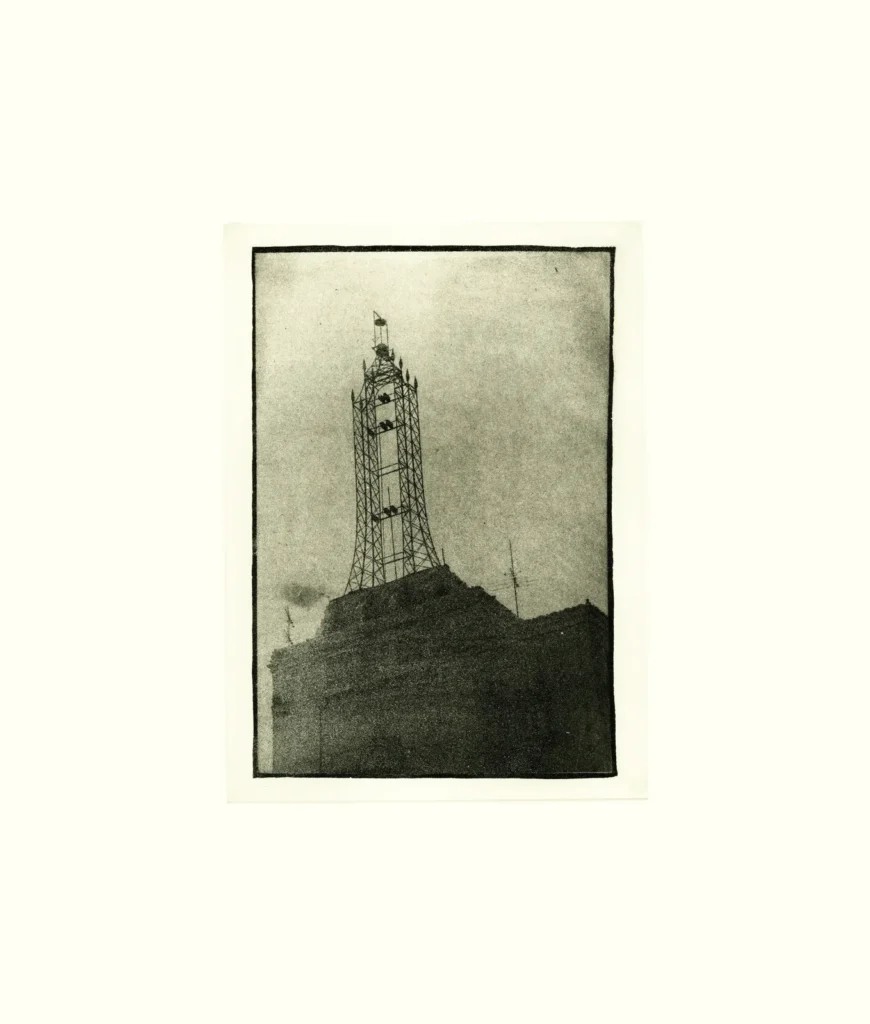

Untitled VIII (1999), a photogravure published by Tandem Press in Madison, belongs squarely within this broader practice. The work sits at the intersection of Lynch’s obsession with texture and decay, his fascination with dream logic, and his conviction that images should operate less as illustrations than as portals—objects capable of provoking psychological unease, reverie, or revelation without ever resolving into tidy narratives.

Printed in a limited edition and hand-signed on the verso, bottom right, Untitled VIII is formally modest yet conceptually expansive. It is a work that rewards prolonged looking, its photogravure surface functioning as both image and terrain. In this sense, the print exemplifies what has made Lynch one of the most influential American artists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: his ability to render inner states visible while refusing to explain them.

stir

Photogravure is among the most technically demanding and sensuous of printmaking processes. Combining photography with intaglio printing, it involves transferring a photographic image onto a copper plate coated with light-sensitive gelatin, which is then etched and inked before being run through a press. The result is a print with extraordinary tonal depth—velvety blacks, smoky mid-tones, and luminous highlights that feel closer to charcoal or oil paint than to mechanical reproduction.

For an artist like Lynch, whose visual language thrives on murk, abrasion, and atmospheric density, photogravure is a natural fit. His films are famous for their darkness—not merely in a moral or narrative sense, but in a literal, optical one. Shadows swallow rooms; faces emerge from blackness; textures accumulate like residue. In Untitled VIII, that cinematic chiaroscuro is distilled into a single, suspended moment.

The medium’s tactile qualities also align with Lynch’s long-standing fascination with surfaces that appear wounded, corroded, or unstable. Even when pristine in physical condition—as this example is—the image itself often suggests something eroded or in flux, as though the paper were recording the afterimage of an event rather than the event itself.

Tandem Press, the Madison-based workshop that published the edition, is renowned for collaborating with major contemporary artists on technically ambitious print projects. Their involvement situates Untitled VIII within a lineage of fine-art printmaking that treats the multiple not as a lesser cousin to painting, but as an autonomous, experimental arena.

untitled

Lynch’s choice to leave the work untitled is not incidental. Across his films, paintings, and prints, he frequently avoids explanatory captions, preferring to let images remain unresolved. Titles, he has suggested in interviews, can close off interpretive possibilities; an untitled work remains open, hovering between meanings.

In the case of Untitled VIII, the Roman numeral implies a sequence, hinting that this print belongs to a larger body of related works rather than standing alone as a singular statement. The viewer encounters not a definitive picture, but a fragment from an ongoing investigation into form, mood, and psychic atmosphere.

This serial logic echoes Lynch’s cinematic structures, particularly in projects like Twin Peaks, where motifs recur across episodes and seasons—red curtains, zigzag floors, flickering lights—accumulating resonance without ever being fully decoded. Similarly, Untitled VIII feels like one panel in a private mythology, a page torn from a notebook of visions.

view

Although each impression of Untitled VIII must ultimately be encountered in person to grasp its full complexity, Lynch’s photogravures from this period typically feature abstracted or semi-figurative forms embedded in fields of shadow. Smears, stains, and ghostly silhouettes hover within the composition, suggesting walls, bodies, machinery, or organic growth without stabilizing into any single identity.

Darkness functions here not as absence but as substance. It pools, thickens, and presses forward, creating a sense of spatial ambiguity that mirrors the dreamscapes of Lynch’s cinema. One might think of the industrial wastelands of Eraserhead, the nocturnal suburbia of Blue Velvet, or the endless corridors of Lost Highway—all environments where menace and beauty coexist in uneasy equilibrium.

The photogravure process amplifies this effect. Because the ink sits within etched recesses in the plate rather than on the surface of the paper, blacks acquire a depth that seems to sink into the sheet itself. The image does not float; it embeds. The viewer is drawn inward, peering into layers rather than scanning across a flat field.

flow

Lynch is frequently associated with violence, dread, and the grotesque, yet he has long insisted that his work is equally rooted in transcendence. An outspoken advocate of transcendental meditation, he has described creativity as a process of diving beneath surface thoughts into a reservoir of images and ideas that feel at once terrifying and ecstatic.

In statements about his own working habits, Lynch has recalled sitting in well-lit diners so that he could safely drift into darker mental territory, confident he could always return to light. That oscillation—between safety and danger, illumination and obscurity—animates Untitled VIII.

The print does not simply confront the viewer with horror; it invites a quieter, more contemplative engagement. The absence of explicit narrative detail encourages a meditative mode of looking, in which the eye wanders across tonal gradients and textural irregularities. Fear and calm coexist, producing the peculiar emotional register that has become Lynch’s signature: unsettling yet hypnotic, threatening yet strangely serene.

rare

From a collecting standpoint, Untitled VIII occupies a compelling position within Lynch’s oeuvre. Issued as a limited-edition photogravure and accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from the gallery, the print exemplifies the artist’s blue-chip status in the fine-art market.

Lynch is represented by internationally recognized galleries and collected by major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Colección SOLO in Spain. His exhibitions—such as David Lynch: I Like to See My Sheepat Sperone Westwater in 2022 or Squeaky Flies in the Mud in 2019—have consistently reinforced his standing not merely as a filmmaker who dabbles in visual art, but as a serious, institutionally validated artist whose studio practice runs parallel to his cinematic output.

The pristine condition of the print, combined with the absence of a frame, offers collectors both assurance and flexibility: assurance in the integrity of the sheet, and flexibility in presentation, whether floated in a museum-style mount or integrated into a more theatrical display that echoes Lynch’s immersive installations.

exhibition

Recent decades have seen Lynch’s visual art increasingly contextualized within museum and gallery spaces rather than treated as peripheral curiosities. Exhibitions such as Barjola, an apocryphal portrait at Colección SOLO in 2025 underscore the international appetite for his non-cinematic work, while his long-running relationship with Sperone Westwater has provided a consistent platform for presenting paintings, drawings, and prints to a fine-art audience.

Within these settings, photogravures like Untitled VIII are often displayed alongside heavily worked canvases and sculptural assemblages, allowing viewers to trace the continuity of Lynch’s imagery across media. The same tar-like blacks, fleshy pinks, and corroded whites recur whether rendered in oil paint, charcoal, or etched copper plates.

Institutional framing has also encouraged critics to revisit Lynch’s place within postwar American art, situating him in dialogue with figures such as Francis Bacon, whose distorted bodies and existential dread resonate strongly with Lynch’s own pictorial language, or with the assemblage traditions of artists who treated found materials as carriers of psychological charge.

media

The involvement of Tandem Press is more than a footnote. Founded in 1985, the workshop has built a reputation for technical rigor and for fostering close collaborations between artists and master printers. For Lynch, whose interest in process is as intense as his interest in imagery, such a partnership would have been essential.

Photogravure demands patience and experimentation: plates must be exposed, etched, proofed, and reworked; tonal balances adjusted; papers selected for their absorbency and surface. Each decision affects the final mood of the image. In Untitled VIII, the seamless integration of image and material testifies to a production process in which concept and craft are inseparable.

This emphasis on making—the physical labor behind the print—mirrors Lynch’s own studio habits. He is known for working directly with materials, staining canvases, embedding objects into surfaces, and allowing accidents to guide compositions. The photogravure, though mechanically mediated, retains that sense of tactile engagement.

cin

One of the most compelling aspects of Lynch’s prints is how insistently they avoid illustrating specific scenes from his films. Untitled VIII does not depict a recognizable character or location from Twin Peaks or Blue Velvet. Instead, it operates at a more abstract level, distilling the emotional and atmospheric qualities of his cinema into a standalone visual object.

This refusal of literal reference is crucial to understanding Lynch’s cross-media practice. His paintings and prints are not ancillary merchandise or storyboards; they are parallel explorations of the same psychic territory. Just as his films often leave narrative threads unresolved, his images resist symbolic closure.

Viewers may sense echoes of industrial landscapes, wounded bodies, or claustrophobic interiors, but these associations remain provisional. The work functions less as a riddle to be solved than as a mood to inhabit.

why

Created in 1999, Untitled VIII belongs to a moment when Lynch was already an established cinematic icon, fresh from the release of Lost Highway and on the cusp of embarking on projects that would further complicate his legacy. That he continued to invest serious energy in printmaking during this period speaks to the independence of his visual-art practice.

In the current market, where boundaries between disciplines are increasingly porous and filmmakers regularly cross into gallery contexts, Lynch stands as a precursor. His commitment to fine art long predates the contemporary vogue for multimedia celebrity, and works like Untitled VIII demonstrate that this commitment was never superficial.

For collectors and scholars alike, the print offers a concentrated encounter with Lynch’s visual thinking—an opportunity to engage with his obsessions stripped of cinematic apparatus and narrative scaffolding. It is Lynch at his most distilled: darkness, texture, ambiguity, and quiet intensity compressed into a single sheet of paper.

impression

Untitled VIII (1999) exemplifies what makes David Lynch’s art endure across media. It is not a decorative object nor a simple collectible tied to a famous director’s name. It is a work that insists on being experienced slowly, physically, and introspectively.

Through the alchemy of photogravure, Lynch transforms shadow into substance and ambiguity into invitation. The limited-edition print, pristine and hand-signed, stands as both a market object and a metaphysical proposition: a reminder that images can function as thresholds, leading viewers into spaces that are unsettling, seductive, and profoundly their own.

In that sense, Untitled VIII does precisely what Lynch has always demanded of art. It does not explain the darkness—it lets us sit with it, long enough to discover that it is not empty at all.

No comments yet.