In 2022, the final public pay phone in New York City was removed—a small, bureaucratic gesture that nonetheless marked the end of something massive. With it went the last remaining trace of a pre-digital New York, a city where fixed communication points tethered strangers together by metal, plastic, and quarters. For most, the pay phone’s demise passed with a shrug. But for photographer Daniel Weiss, it signaled a crucial turning point in the story of urban life.

His new photo book, Pay Phone, is not simply a nostalgic memorial—it is a deeply textured documentary project, a ten-year chronicle of isolation, spontaneity, grit, and evolving public space. Between 2008 and 2020, Weiss roamed the five boroughs—primarily Manhattan—capturing images of phone booths, their users, and the city’s shifting anatomy. The result is a monograph both intimate and archival, balancing portraiture with architectural decay, social commentary with aesthetic inquiry.

“Long ago,” Weiss tells us, “we traded human interaction for the quiet isolation of screens.” Pay Phone feels like an attempt to dial back, if not to a better time, then at least to a more tangible one.

THE CONCEPT: FIXED POINTS IN A CITY OF MOTION

Weiss began photographing pay phones without knowing it would become his signature body of work. “They interested me,” he says plainly. “And I included them in my pictures whenever possible.”

At first, the booths were incidental—background textures in larger street scenes. But as they began to disappear from the cityscape, their value as photographic subjects intensified. Weiss sharpened his lens, began centering them in the frame, treating them not just as props, but as protagonists.

He didn’t know he was documenting extinction. But like all great documentarians, he recognized when the ordinary became historic.

The photographs in Pay Phone are not uniform. Some center the booth with reverence; others use it as foil, a jagged relic amid the gloss of new construction. Occasionally, advertisements peel from their Plexiglas walls, graffiti blooms across their faces, or pigeons gather like mourners at their base. These are not staged tableaux. They’re honest city portraits—unplanned, imperfect, and achingly true.

PORTRAITS IN PLACE: A STAGE OF GLASS AND METAL

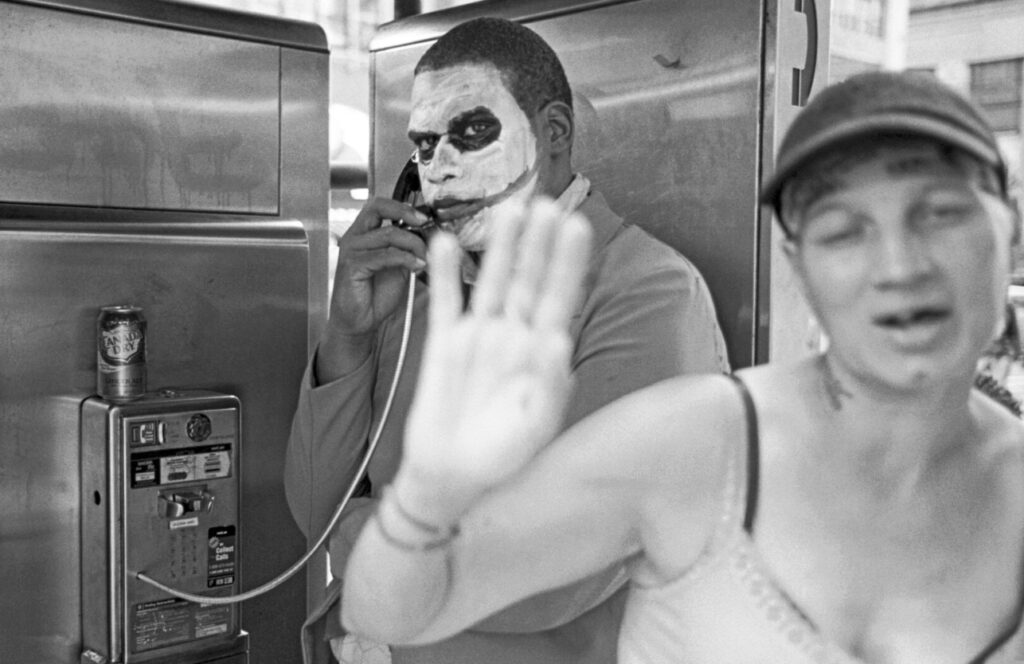

A defining feature of Pay Phone is the inclusion of portraits. Weiss didn’t just shoot empty booths—he invited people into the frame. “The phone booths were the perfect backdrop,” he explains. “I used them like a stage, to help separate the subject from the noise of the city.”

This metaphor—a stage—proves instructive. In an urban environment dense with movement and distraction, the phone booth provided an accidental proscenium, framing whoever stepped within. In Weiss’s work, this manifests in stunning ways. A woman in a plastic poncho leans against the receiver box. A child clutches a payphone cord as if it were a lifeline. A man in a suit squints into the metallic booth as if trying to decode a memory.

Sometimes, the booths themselves became characters—half-sentient, half-symbolic. They stand in for a past we’re trying not to forget, and sometimes a present we’re desperate to explain. Their decayed exteriors reflect the bruised, bustling, brilliant humanity around them.

DOCUMENTING A GEOGRAPHY OF LOSS

All of the photographs in Pay Phone were taken in Manhattan—a deliberate constraint. “The book has pictures from all over the island,” Weiss says, “from the Lower East Side to the Upper West Side. Many in midtown, which had the highest concentration of pay phones and people.”

This focus gives the project a topographical coherence. The pay phone becomes a fixed element across multiple terrains—gentrifying neighborhoods, tourist corridors, business districts, and residential zones. In this way, Weiss turns the booth into a geographic constant. A compass, even.

In Midtown, the booths feel like fossils—cracked underfoot, ignored by pedestrians. In the Lower East Side, they’re more expressive, festooned with stickers and tags, little shrines to subcultural histories. On the Upper West Side, the booths exude a quieter, more melancholic energy, standing as ghost limbs of an analog era.

With this locational variation, Pay Phone paints a fuller portrait not just of a device, but of a city coming undone and reforming itself again.

TECHNIQUE AND TIMING: A DECADE OF OBSERVATION

The photographs span from 2008 to 2020—a time of dramatic transformation for New York. Gentrification surged, social media exploded, and the economic polarity of the city sharpened. What began as a loose project turned into a temporal capsule, each frame infused with context: the post-recession grit of 2008, the Instagram gloss of the mid-2010s, the eerie hush of early pandemic days.

Weiss’s method was instinctive, not calculated. He often worked quickly, capturing candid portraits and street scenes in natural light. His style recalls that of his heroes—Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus—each of whom wielded the camera like a sociological tool.

The influence is clear. From Evans, he inherits architectural rigor. From Frank, a poetic melancholy. From Arbus, the ability to find mystery in the mundane.

But Weiss is no mimic. His images resist irony or judgment. Even when subjects are caught off guard, there’s a sense of respect—of the artist asking not “What’s wrong with this?” but “What’s human about this?”

SYMBOLISM AND ABSENCE: WHAT THE PAY PHONE MEANS NOW

When asked what the final removal of a pay phone in NYC meant to him, Weiss is blunt: “It is the end of an era. The end of the New York that I grew up in.”

It’s easy to over-romanticize the past. Weiss doesn’t. He acknowledges the impracticality of pay phones today. But their value, he argues, was never purely functional. They were visual symbols of public access, spontaneity, and chance.

To encounter someone on a pay phone was to glimpse a private moment made public. You could hear part of the conversation. You could witness the urgency of it, the posture of the speaker, the coins rattling in their palm. These were social rituals. They belonged to the architecture of intimacy.

Smartphones privatized that. They gave us convenience but robbed us of spectacle. “We’re still all packed in here physically,” Weiss says, “but long ago we traded human interaction for the quiet isolation of screens.”

The removal of pay phones didn’t just erase a technology. It erased a mood.

THE BOOK AS OBJECT: A MONOGRAPH WITH MEMORY

Pay Phone is Weiss’s first monograph—a milestone in any photographer’s career. “I learned a lot,” he says, “mostly about what it really takes to get a book into the world.”

It was always the intended form for this work. Though many of the photos have been shared online or exhibited, the physical book offers something uniquely tactile. It’s a way to hold a vanishing city in your hands. To flip through images of a world that no longer exists but still breathes on paper.

Weiss sequenced the book himself, favoring emotional rhythm over chronology. Some spreads feature lonely booths; others juxtapose portraits with architectural decay. Together, they unfold like a slow walk through the city, eyes up and open.

He’s already working on more—ten other books, in fact. But Pay Phone will remain a cornerstone. It’s the one that captures the rupture.

A CITY IN TRANSITION: WHAT’S NEXT FOR NEW YORK?

Between 2008 and 2020, New York transformed beyond recognition. Weiss saw it all: the vanishing mom-and-pop shops, the rise of glass towers, the disappearance of spontaneity.

He doesn’t romanticize the past, but he does mourn its clarity. “The city has changed dramatically,” he says. “It’s lost a lot of the character I was interested in capturing.”

Pay Phone functions as both elegy and artifact. It’s not just about phones. It’s about context—about what it meant to live publicly, to be reachable and exposed. It’s about a kind of performative intimacy we’ve since buried under apps and noise-cancelling headphones.

But Weiss is not done. “It’s harder to photograph here now,” he admits, “but I like a challenge. And there are still pictures to make. New York is still my home.”

HANGING UP, or HOLDING ON

Daniel Weiss’s Pay Phone is not a trip down memory lane. It’s a map of emotional geography, etched in concrete and Plexiglas. Through a seemingly obsolete object, he explores presence, loss, and the strangeness of modern connection.

The pay phone, in his lens, is both anchor and ghost. A place where conversations began. A place where people waited, wondered, or wept. A place that, even in its silence, had something to say.

And while the booths are gone, Weiss has given them a second life—one of paper, grain, backdrop, and light.

No comments yet.