Street art has long survived on a paradox: it is a culture built on rupture, yet paradoxically allergic to being ruptured itself. It celebrates disruption but bristles at being disrupted. And in the last twenty years — after global expansion, mass gentrification, commodification, and the rise of the “mural festival” economy — street art has reached a moment when critique is not only appropriate, but essential. The British artist Ed Hicks enters this conversation with an argument both unfashionable and necessary: that street art, for all its rebellious origin myths, must welcome critical scrutiny if it wants to maintain its intellectual and cultural vitality.

Hicks speaks in defence of critique not as an outsider wagging a finger at the scene, but as a participant with a clear affection for the medium. His work, oscillating between macabre whimsy and baroque dystopia, carries technical rigor and conceptual commitment. Yet he is also increasingly vocal about the stagnation he perceives within the broader street-art ecosystem — specifically, its drift toward aesthetic repetition, superficial activism, and corporate safety. To defend critique is, for Hicks, to defend the possibility of evolution.

This editorial examines Hicks’s position, the tensions embedded in contemporary street art, and why criticism — honest, informed, and at times uncomfortable — may be the only way forward.

myth

The critique-resistant posture of street art begins with its mythmaking. The movement romanticizes itself as anti-institutional, anti-market, anti-control. Origin stories are filled with scrappy teens evading authorities, rail yards coated in coded messages, battles over territory and style. This mythology offers comfort — a kind of nostalgic frontier mentality — even as the scene has grown into a global economic engine.

Today’s street art sits at the intersection of commerce and culture:

• mural festivals backed by municipal grant funds

• real-estate developers hiring artists to increase property value

• shoe brands commissioning quick-turn “street-inspired” visuals

• tourist districts using murals as landmarks for influencers

The public-facing language still frames street art as transgressive, yet the lived reality is safer, more regulated, and increasingly corporate-friendly. Hicks argues that the refusal to acknowledge this shift — the clinging to a myth of purity — prevents necessary dialogue about quality, intent, and ethics.

Critique, in this context, functions like a flashlight. It illuminates the difference between the romanticised story and the actual ecosystem artists inhabit. Without it, street art risks becoming a caricature of itself.

ed

Hicks’s own practice reveals why critique matters. His paintings and murals carry strong visual density, a cinematic sensibility, and often a dark humour that refuses easy categorization. Rather than purely decorative or instantly “Instagrammable,” they reward slow looking. He paints with an understanding of composition that borrows from classical techniques as much as from underground comics — an unusual combination within the street-art sphere.

When Hicks advocates for critique, he isn’t elevating himself above the field; he’s advocating for a more serious discourse around the craft. He believes artists benefit from being challenged: to refine technique, interrogate themes, acknowledge influences, and consider the cultural footprint their work leaves. He is equally sceptical of the inflated praise often directed at mediocre public artworks because they appear “accessible” or “fun.”

For Hicks, good work endures because it withstands pressure. Poor work collapses under questioning. The goal isn’t gatekeeping — it’s raising the ceiling.

mural

One of Hicks’s clearest critiques concerns the “mural festival style,” a shorthand aesthetic that has dominated public art in the 2010s and 2020s. These murals are typically:

• colourful

• optimistically themed

• illustrative rather than conceptual

• safe enough to appeal to city councils and developers

• designed with social media scalability in mind

There is nothing inherently wrong with this work, Hicks notes, but the homogenization of style has consequences. Aesthetic stagnation sets in when artists feel pressured to produce images that conform to safe expectations — and when critical voices are dismissed as elitist, negative, or “overthinking it.”

Hicks argues that when artists and audiences avoid critique in the name of friendliness or community solidarity, they inadvertently lower the quality of public art. The result: cities full of pretty walls, but fewer meaningful ones.

show

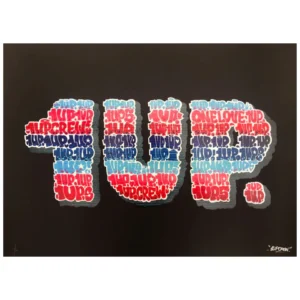

Critique also matters because street art occupies a contested space between graffiti culture and institutional art worlds. Graffiti has traditionally relied on internal critique — competition over style, placement, originality, lineage. Writers debate each other constantly, often harshly, and this friction pushes the culture forward.

Street art, by contrast, frequently presents itself as inclusive and noncompetitive. While this ethos sounds appealing, it can limit artistic growth. Without the productive tension that graffiti embraces, street art risks drifting into uncritical friendliness — a culture of applause rather than evaluation.

Hicks’s position implicitly suggests that street art might borrow some of graffiti’s critical toughness while maintaining its broader accessibility. Critique need not be antagonistic; it can be aspirational, pushing artists toward deeper engagement with their ideas and their form.

flow

Another phenomenon Hicks identifies is what he calls the “politics of positivity.” Within the street-art community, there’s often pressure to avoid negative assessments for fear of damaging reputations or community harmony. Artists are encouraged to support one another unconditionally, which sounds noble but can create a culture hostile to honest feedback.

This positivity-driven atmosphere discourages risk-taking. As Hicks notes, if all works are treated as equally valid, artists have little incentive to experiment, challenge themselves, or confront uncomfortable truths. Critique sharpens intentions; it helps artists better understand what they’re doing — and why.

Street art that avoids critique often becomes art that avoids meaning.

crit

Hicks also insists that because street art exists in public space, it must withstand public scrutiny. Unlike gallery art, which audiences opt into, murals belong to everyone. They shape how neighbourhoods feel and function. They communicate values, sometimes subtly and sometimes loudly.

For Hicks, this public visibility creates a responsibility. Artists who insert their work into the shared urban environment must be prepared to face questions:

• What does this imagery communicate?

• Who is it for?

• Does it honour the community or merely decorate it?

• Does it reinforce stereotypes?

• Does it meaningfully contribute to place-making?

These questions are not attacks — they’re the foundation of democratic cultural participation. Without critique, the public’s voice is diminished, and street art becomes a one-way transmission rather than a dialogue.

Another area Hicks highlights is the relationship between street art and commerce. As brands increasingly commission murals, artists face the challenge of maintaining authenticity while navigating market forces. Hicks doesn’t reject commercial work outright; instead, he argues that honest critique helps artists recognise when they are compromising their voice.

The issue is not that artists work with brands; it’s whether the collaboration adds cultural value or simply appropriates street art aesthetics for advertising. Critique can identify such distinctions, protecting both audiences and artists from superficiality.

Without critique, authenticity becomes another marketing slogan.

media

Social media has also reshaped street art into a visual commodity optimised for sharing rather than contemplation. Hicks warns that Instagram culture encourages artists to produce works that succeed in a split-second scroll rather than artworks that reward depth.

Murals become backdrops for selfies, logos of urban coolness, props for tourism. In this environment, critique helps counterbalance the flattening effect of digital platforms. It reminds artists — and audiences — that visual culture can be more than content.

Hicks values the slow processes of making art: research, sketching, failure, revision. He argues that critique reinforces these practices, encouraging artists to resist the pressure to churn out fast, formulaic content.

fwd

Ultimately, Hicks’s defence of critique is rooted in a belief that street art can be more than decorative. He imagines a future in which murals function as civic dialogue, artistic inquiry, and cultural memory — not just tourist magnets or real estate dressing.

To achieve that future, he insists, artists and audiences alike must be willing to engage critically with the work around them. Celebrate what deserves it. Question what needs questioning. And refuse to accept a culture of polite silence.

Street art was born from conflict, confrontation, and courage. Hicks argues that acknowledging that heritage — while updating it for today — can revitalize the medium. Critique doesn’t diminish street art. It returns it to its roots.

fin

Ed Hicks defends critique not to undermine street art, but to protect it. As the medium continues to expand, facing pressures from capitalism, digital culture, and institutional sanitization, the need for rigorous conversation becomes more urgent.

If street art wants to matter — to truly shape public consciousness — it must remain open to interrogation. Critique is not an attack on creativity but a recognition of its power. And in Hicks’s view, a culture unafraid of critique will be a culture capable of producing its most compelling work.

No comments yet.