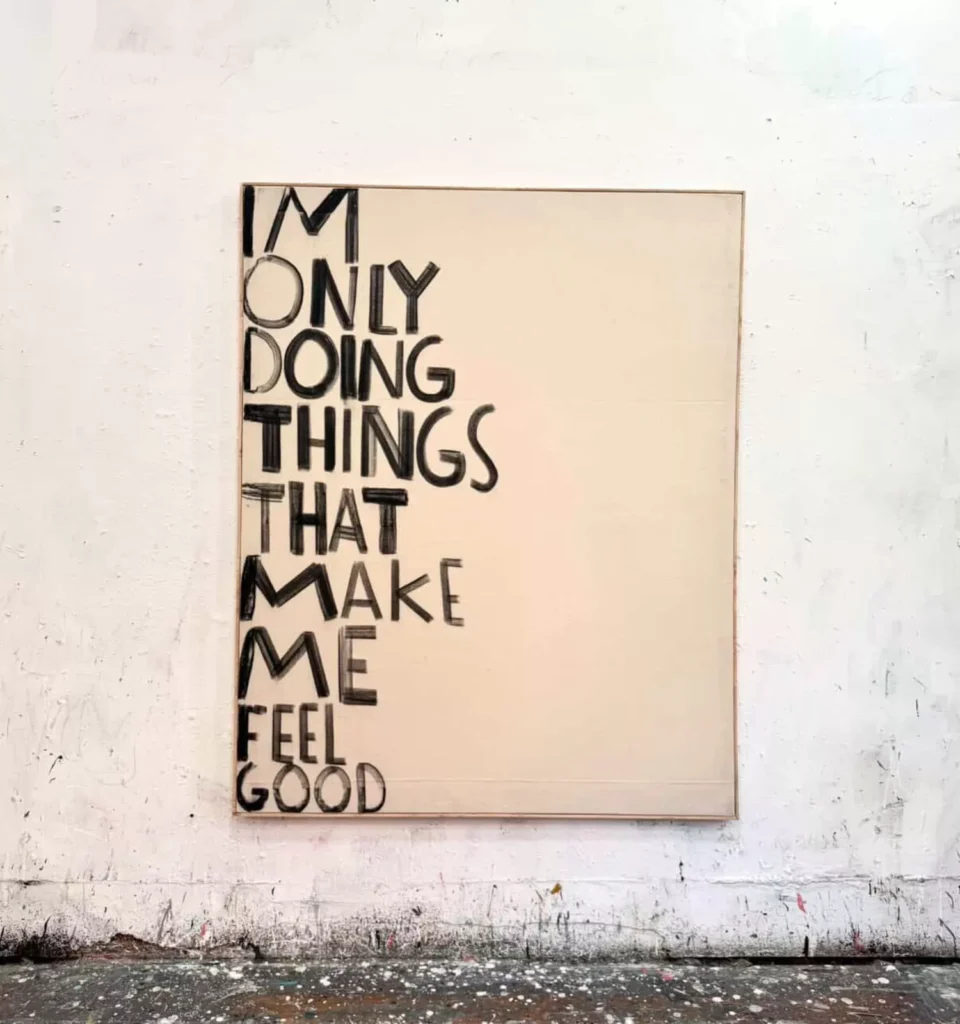

There’s a specific kind of clarity Eric Stefanski achieves when he paints words—an almost accidental serenity that arrives through humor, hesitation, and hand-painted candor. His 2025 work I’m Only Doing Things That Make Me Feel Good is one of those paintings that speaks plainly while revealing something far more unruly underneath. The phrase seems light, even playful, yet the painting holds the psychological density of a private journal entry left open on a kitchen table. There’s intention behind it, but also the vulnerability of a person admitting something they’ve avoided saying for a long time.

Stefanski has always operated in that fragile space between sincerity and sarcasm. He brings the cadence of everyday speech into the arena of contemporary painting without treating it as a gimmick. In I’m Only Doing Things That Make Me Feel Good, the text becomes a quiet manifesto, the kind that doesn’t shout or provoke but instead confesses: I’ve decided to take myself seriously, even if that seriousness arrives through humor. It’s a self-preserving vow disguised as a deadpan.

This is what makes the piece feel so alive. Stefanski’s one-line declaration doesn’t just live on the surface; it leaks into the entire emotional architecture of the painting, merging the textual with the tactile. The phrase becomes a promise, a critique, a plea, and a shrug all at once. It is the rare text piece that recognizes its own complexity without abandoning its directness.

lang

Stefanski’s relationship with language is not conceptual in the traditional sense. He is not doing Lawrence Weiner-style structural linguistics or Jenny Holzer-scale proclamations. Instead, his language emerges from feeling—raw, unadorned, interior. The letters are painted with visible wobble. Some edges slip. Some lines hesitate before regaining momentum. The result is a sentence that still seems to be figuring itself out.

In I’m Only Doing Things That Make Me Feel Good, the phrase sits on a surface full of scuffs, shifts, and subtle disruptions. The background is not passive; it is an emotional echo chamber, carrying the residue of earlier gestures. The layers beneath the text reveal other thoughts—perhaps rejected, perhaps reconsidered—and the final sentence is the one that survived.

Language in Stefanski’s hands is not flat. It is a lived emotional surface. It is thinking made visible.

nuance

Humor is often described as a release valve, but in Stefanski’s work, it becomes something more like a diagnostic tool. His phrases have the tone of jokes that aren’t really jokes. Lines like I’m Only Doing Things That Make Me Feel Goodcarry the rhythm of a self-help affirmation, but the delivery is undercut by a painterly grit that suggests ambivalence.

This is humor used not to deflect but to expose. There is fragility in saying what you want without apology. There is risk in admitting that maybe you’ve spent years doing things that do not feel good. Stefanski’s deadpan voice becomes a structural brace for that vulnerability, a way of giving shape to what might otherwise crumble under its own emotional weight.

The humor is not the point. The honesty is.

flow

While the sentence commands attention, the painting’s imperfections carry equal narrative weight. Stefanski lets the brushwork show its seams. He allows the awkwardness of the hand, the disruptions of the surface, and the inconsistencies of gesture to remain visible.

This approach resists the polished aesthetic of digitally influenced typography that dominates contemporary visual culture. There is no attempt at precision for its own sake. The imperfections become metaphors: doing what feels good rarely looks smooth. It is a process of trying, failing, revising, and recommitting. The painting contains those revisions in its strata.

It becomes clear that the declaration—I’m only doing things that make me feel good—is not effortless. It is earned.

idea

The phrase, on its face, seems simple. Yet simplicity can function as rebellion, especially when life becomes crowded with obligations, deadlines, and unspoken expectations. Stefanski’s message reads like a personal recalibration, a choice to prioritize self-directed pleasure amid cultural burnout.

In a world that measures productivity through output and identity through optimization, saying you will only do what makes you feel good feels transgressive. It challenges the demands of hustle culture and the scripted positivity of social media. It cuts through the noise by refusing to participate in it.

Stefanski’s painting does not promise enlightenment or transformation. It offers something quieter: permission. Permission to care for your inner weather. Permission to leave before exhaustion becomes your personality. Permission to seek pleasure without guilt.

style

If Stefanski’s phrase echoes self-care rhetoric, it also resists it. His work avoids the pastel gradients and sanitized aesthetics of wellness design. The paint is messy, impulsive, and imperfect, a reminder that self-preservation is rarely photogenic.

What makes his text paintings feel diaristic is their refusal to generalize. They do not speak to “the audience” but from the artist’s interior. They are not universal truisms. They are confessions. The viewer recognizes that the message is not advice; it is a record of someone trying to articulate their way through contemporary life.

Stefanski’s candor exposes something many people privately feel: we don’t need another system for optimizing our existence—we need a reason to breathe.

stir

Stefanski’s tone exists in a liminal zone, where sincere desire coexists with ironic self-awareness. This balance is what gives the painting its electricity. The phrase is not naive; it is cautious yet assertive, worn out yet hopeful. It knows how hard it is to live by one’s own emotional barometer, but it still chooses to try.

Sincerity and sarcasm are not opposites in Stefanski’s world. They are companions. They allow the painting to speak both plainly and protectively, inviting viewers into the emotional logic without demanding interpretation.

This duality is not confusion; it is contemporary emotional realism.

fin

As the painting settles into its final impression, what lingers is its gentle insistence. Stefanski does not frame his sentence as a solution, nor as a doctrine. It is simply an articulation of boundary-setting in a world that constantly demands permeability. It is resistance through selective living.

In a cultural moment defined by acceleration, the desire to choose what feels good becomes a radical act of deceleration. It is not selfishness; it is survival. It is not indulgence; it is reclaiming one’s emotional agency.

Stefanski’s painting offers a soft landing for those exhausted by expectation. It is a reminder that sometimes the simplest declarations are the hardest to uphold, and the most necessary to make.

And so the work stands—humorous, honest, imperfect, and profoundly human—as a declaration quietly preparing to change a life.

No comments yet.