In a legislative decision that has ignited national debate and reopened the enduring question of church-state separation, the Texas legislature has voted to require the display of the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom across the state. The bill, introduced by conservative lawmakers and signed into law in 2025, mandates that the biblical text be prominently posted, setting the Lone Star State on a collision course with federal constitutional precedent and cultural pluralism.

To critics, the law is an encroachment on religious neutrality in public education. To supporters, it is a reclamation of moral values and historical legacy. But beyond the familiar political lines, the move invites deeper inquiry into the relationship between faith and governance, the classroom and the cathedral, memory and modernity.

Origins of a Cultural Flashpoint

The Ten Commandments—ancient directives said to have been delivered by God to Moses on Mount Sinai—occupy a unique place in the American imagination. Part legal code, part moral compass, they have appeared in everything from courtroom plaques to Hollywood films. For Christian conservatives, they serve as a foundation for civil society; for others, they are a symbol of religious intrusion into secular life.

Texas has long been a staging ground for these debates. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly upheld the presence of a Ten Commandments monument on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol in Van Orden v. Perry, while simultaneously ruling in McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky that similar displays in public schools violated the Establishment Clause. This legal tension reflects a broader cultural one: can a pluralistic society endorse any single religious tradition within state institutions?

The New Law: What It Says and What It Signals

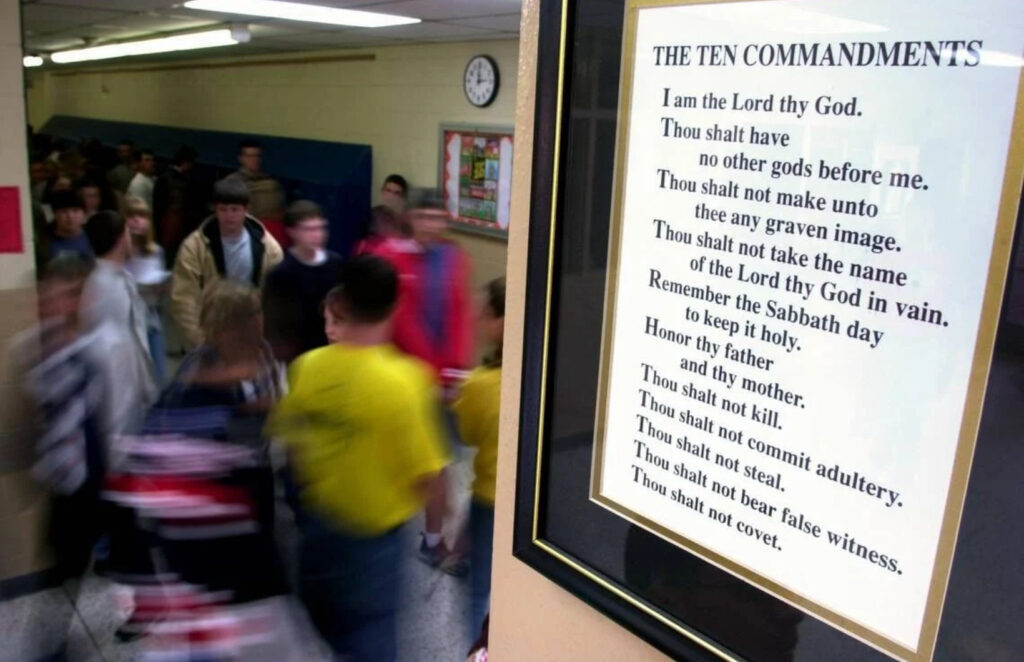

The Texas law mandates that all public K–12 classrooms must display a framed poster of the Ten Commandments at least 16 inches wide and 20 inches tall, with text large enough to be legible from across the room. The law specifies the version of the commandments to be used—an ecumenical translation that attempts to unify Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish variations but inevitably fails to satisfy all.

Proponents claim the law restores moral clarity and acknowledges the Judeo-Christian heritage of the United States. Governor Daniel Pryce, in his signing statement, said, “The Ten Commandments are not just religious guidelines—they are the bedrock of our legal tradition. If we can post stop signs and dress codes, we can post the principles that teach respect for life, property, and truth.”

But critics see something else. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas has already filed suit, arguing that the law violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits government endorsement of religion. Civil rights groups and interfaith organizations have warned of alienation, especially for students from non-Christian or secular households.

A Battle for the Classroom’s Soul

Public school classrooms are not neutral spaces. They are where national narratives are cultivated, behaviors socialized, and values transmitted. What is posted on a classroom wall is not just décor—it is declaration. The alphabet teaches literacy. Maps teach geography. The Ten Commandments, then, teach what?

To some, they teach reverence for divine law. To others, they signify exclusion—an implicit ranking of belief systems, with monotheistic Christianity or Judaism atop the podium. In schools where children of Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, atheist, and other backgrounds sit side-by-side, the state’s endorsement of one faith’s doctrine raises pedagogical and ethical questions.

Imagine a seventh-grade classroom in El Paso or Houston—students of diverse races, languages, and traditions. What message is conveyed when they look up from a math test and read: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me”? Is it instruction? Inspiration? Indoctrination?

Historical Memory and Revisionism

Supporters of the law often invoke the Founding Fathers as religious men who built a Christian nation. Yet historical scholarship reveals a more complex picture. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, principal architects of the First Amendment, were wary of religious entanglement in state affairs. Madison wrote: “The civil magistrate is not a competent judge of religious truth.”

Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom became the blueprint for disestablishment in the U.S., and he famously cut and rearranged the New Testament to remove miracles, producing what’s now known as the Jefferson Bible. Far from being zealots for theocracy, many early leaders saw religion as a private matter and feared the chaos of sectarian rule.

Still, the Ten Commandments have persisted as civil symbols. They appear in the frieze of the U.S. Supreme Court building alongside Confucius and Solon, as markers of legal heritage rather than religious creed. But context matters. On a courtroom wall, they are part of a tapestry of world law. In a Texas fourth-grade classroom, standing alone, they become something else: a curriculum without consent.

Constitutional Reckoning: What Comes Next?

The legal fate of the Texas law will likely end up before the Supreme Court, especially given its open defiance of prior rulings. The Court’s composition has shifted rightward in recent years, and its willingness to revisit longstanding precedents—on issues from abortion to affirmative action—suggests the Ten Commandments mandate may get a sympathetic hearing.

In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the Court ruled in favor of a public school football coach who prayed on the field, indicating a loosening of the “Lemon test,” which had governed church-state cases for decades. The decision emphasized “historical practices and understandings” over perceived endorsements.

This interpretive shift opens the door for arguments that the Ten Commandments are cultural artifacts, not religious decrees. If they are historical rather than devotional, the state might argue, their presence is educational, not ecclesiastical.

But such framing skirts the obvious: the commandments begin with a divine voice and end with moral imperatives. Their syntax is sacred, not civic.

National Implications: A Policy Ripple Effect

Texas is rarely alone in culture war legislation. It often functions as a legislative bellwether, exporting policy models to other Republican-led states. Already, lawmakers in Louisiana, Florida, and Mississippi have introduced similar measures. The Ten Commandments may soon become a new national battleground—replacing CRT bans and book challenges as the next ideological flare.

This trend is not without historical precedent. In the 1950s, during the Cold War, a similar push emerged to establish America’s spiritual superiority to atheistic communism. “In God We Trust” became the national motto. “Under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance. The Ten Commandments were posted in schools and courthouses in symbolic defiance of godless foes abroad.

Today, the perceived enemy is not a foreign ideology but moral relativism, secularism, and what conservative leaders call the “erasure of faith from public life.” The classroom becomes the front line.

Educational Fallout: Teachers, Students, and the Day-to-Day

Lost in the legal and political clamor are the voices of educators and students who must navigate the law in real time.

Teachers, already stretched thin, now face the added challenge of contextualizing religious text within a secular syllabus. Do they ignore the commandments entirely? Engage in comparative religion? What happens when a student asks why the school posts one religion’s sacred law and not another’s?

Some teachers may feel empowered; others will feel constrained. And in districts where religious diversity is high, classrooms may become tense zones of identity negotiation. The commandments, instead of uniting students around universal truths, risk splintering them along lines of belief.

A Test of Democratic Pluralism

The deeper question is not whether the Ten Commandments are good or bad, but whether the state should wield religious symbols in civic spaces.

Democracy is not homogeneity. It is a shared structure of governance among disparate peoples, beliefs, and backgrounds. Public schools are among the last truly democratic institutions—places where all children, regardless of creed, are entitled to the same education.

By inserting one religious doctrine into every room, Texas risks breaching that neutrality. It replaces pluralism with proclamation, education with evangel.

Impression

The Ten Commandments law in Texas is not just about what hangs on a wall. It is about what lives in the walls of our institutions—what we believe the public sphere should reflect, endorse, and protect.

For some, the commandments offer moral clarity in an age of confusion. For others, they are reminders of a state choosing sides in a nation meant to embrace all. Either way, their posting is not benign. It is declaration, etched not in stone but in policy.

And like all declarations, it will be tested—not only in courts of law, but in the daily rituals of classrooms where America’s future sits, reads, learns, and wonders what exactly it means to be free.

No comments yet.