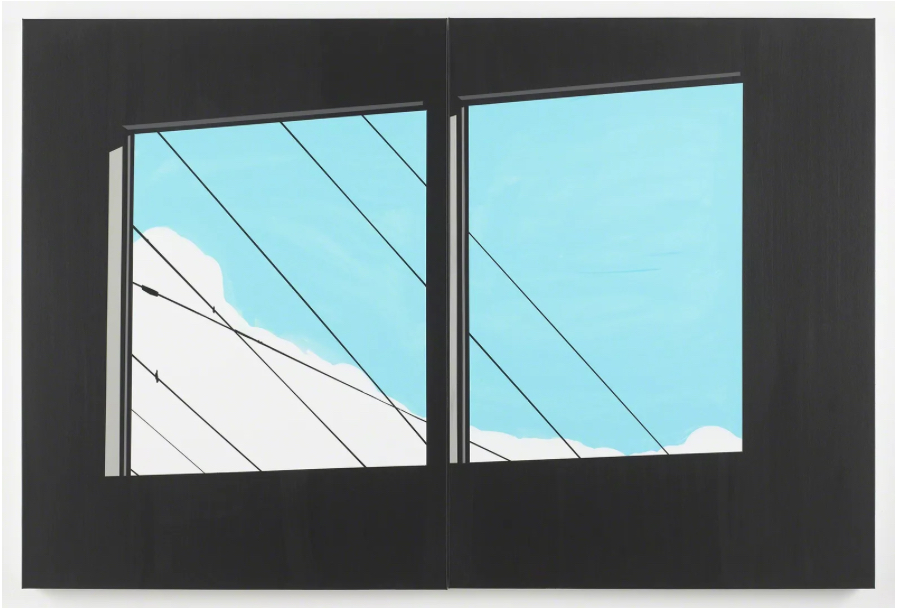

In Windows (2018), Brian Alfred doesn’t just paint an interior view—he captures a state of mind. Executed in his signature flat acrylic style, the work is an exercise in calm, control, and contradiction. It’s quiet but charged. Still, but not static. On its surface, it’s deceptively simple. Yet the longer one stays with it, the more it reveals: not just about Alfred’s vision, but about our own fractured way of seeing.

This isn’t just a painting. It’s a pause. A psychological aperture into the way we live, observe, and isolate ourselves in the modern world.

The Language of Flatness

Brian Alfred is known for his distinctive visual language: flat planes of color, clean lines, digitally influenced aesthetics. His paintings often feel like screen captures—stripped of texture, depth, and backdrops. But don’t mistake this flatness for superficiality. What Alfred achieves is a kind of visual paradox: by flattening space, he deepens meaning.

In Windows, the flatness works to sharpen focus. The absence of expressive brushwork or painterly detail forces us to engage differently—with composition, with form, with suggestion. Every object becomes more symbolic than literal. Every shape becomes a sign. It’s painting, but it’s also design. Architecture. Interface.

What looks simple is actually rigorously constructed.

Reading the Room: Interior as Portrait

At first glance, Windows appears to be a straightforward interior—furniture, a view, a quiet atmosphere. But Brian Alfred has always been more interested in environments as psychological mirrors. His interiors aren’t empty—they’re charged with implication. What’s included matters, but what’s omitted often matters more.

In Windows, we see no people. But we feel their presence, or perhaps their absence. The room becomes a kind of portrait—not of a person, but of a presence. The arrangement of space and objects offers clues to a lifestyle, a mood, a mindset. The furniture is minimal. The palette is subdued. The outside view is controlled. There’s harmony, but also restraint.

Is this peace or detachment? Contentment or loneliness? Alfred doesn’t answer. He invites us to sit with the question.

The Window as Metaphor

The title Windows does more than describe an architectural feature—it unlocks the entire painting. Windows are boundaries and thresholds. They separate and connect. They let in light, but also divide the inside from the outside. They’re about looking out, and being looked at.

In Alfred’s Windows, these layers are palpable. The windows frame a view, but they also suggest a barrier. We don’t know what’s outside—just that it’s out there. And we don’t know who’s inside—just that they’re enclosed. It’s a painting about perception. About how we frame the world, and how the world frames us.

There’s also a not-so-subtle echo here of digital windows—the kind we stare at all day on screens. Alfred, who often references technology and modern media in his work, knows exactly what he’s doing. This is both an actual window and a metaphorical one—a portal that might be real or virtual. We’re always looking through something, he seems to say. But are we really seeing?

Color, Control, and the Politics of Calm

One of the most striking aspects of Windows is its color palette: soft neutrals, muted blues, earthy tones. Nothing shouts. Everything is deliberate. It’s a palette of control, order, composure. And yet, in a world saturated with noise and chaos, this calm feels almost political.

Alfred’s refusal to indulge in visual excess is a kind of quiet resistance. In a media culture addicted to spectacle, Windows chooses stillness. In a time of overstimulation, it chooses focus.

But there’s tension underneath. The peace feels curated. The harmony feels designed. Is this serenity, or suppression? Is this a sanctuary, or a retreat from reality? Again, Alfred doesn’t resolve these questions. He stages them.

The Influence of Place and Architecture

Brian Alfred’s work has always drawn from real environments—urban landscapes, modernist buildings, minimalist interiors. He studies space not just as a backdrop, but as a character. In Windows, this sensitivity to architecture is clear. The lines are clean. The proportions are precise. The furniture is spare but intentional.

There’s a modernist echo in the scene—perhaps mid-century, perhaps contemporary. The style suggests taste, money, education. But it also suggests a certain kind of lifestyle: curated, insulated, aesthetically aware.

Architecture here isn’t neutral. It’s expressive. It tells us about values, choices, identities. Alfred’s interiors aren’t just places—they’re positions.

Acrylic as Statement

Medium matters, and for Alfred, acrylic is a deliberate choice. Its quick drying time, matte finish, and smooth application suit his method. But more than that, it mirrors his subject matter: surface, media, screens.

Oil would be too lush, too expressive. Acrylic gives Alfred the control he wants. It allows for precision without emotion. It’s a medium of restraint, of flatness, of form.

In Windows, the acrylic doesn’t just depict a scene—it embodies it. The surface is as smooth and sealed-off as the room itself. You can’t enter. You can only observe.

Digital Influence and Visual Culture

Alfred’s visual style has often been compared to vector art, animation cells, and computer renderings. This is no accident. He frequently uses digital tools in his process, and his paintings often feel like stills from a larger digital narrative.

In Windows, this influence shows in the clean outlines, the uniform colors, the absence of texture. But more than technique, it’s about how we see. We are all conditioned now to view the world in screen-like segments—framed, filtered, flattened.

Alfred isn’t just reflecting that reality—he’s critiquing it. Windows is a painting, but it’s also a statement: about mediation, about control, about the quiet anxiety of seeing everything and feeling less.

Isolation and the Contemporary Psyche

Painted in 2018, Windows predates the global pandemic by two years. But in hindsight, it feels prophetic. The sense of interiority, of removed observation, of curated calm—all of it anticipates the emotional atmosphere of lockdown life.

Suddenly, we all lived in our own Windows. Watching the world from inside. Framed, disconnected, searching for meaning in stillness. Alfred’s painting didn’t just capture a moment—it foreshadowed a collective experience.

This gives the work a new layer of meaning. What once seemed like minimalist detachment now reads as emotional survival. The question is no longer just “what’s outside?” but “how do we stay human when we can’t go out?”

Narrative Without People

There are no people in Windows, but there is narrative. The scene suggests life just off-frame. A story implied but untold. This is a hallmark of Alfred’s work: the viewer becomes the protagonist. We fill in the blanks. We supply the absence.

It’s also a challenge. In a world obsessed with identity and personality, Alfred resists. He refuses to show us faces, emotions, drama. Instead, he gives us space—literally and figuratively. What we project onto that space reveals more than any character could.

This is narrative by architecture. Storytelling through stillness. It’s not passive—it’s participatory.

Impression

In the age of infinite scroll and instant reaction, Brian Alfred’s Windows asks us to slow down. To look without distraction. To sit with ambiguity. It’s a painting that rewards time, not clicks.

Alfred’s genius lies not in spectacle, but in restraint. He shows us how much can be said with how little. He gives us silence, and asks us to listen.

Windows is not a painting that demands your attention. It’s one that deserves it.

A Window into Modern Consciousness

With Windows, Brian Alfred doesn’t just depict a view—he frames a cultural condition. The painting is calm, composed, and quietly profound. In its stillness, it invites us to consider our own interiors—our spaces, our habits, our ways of seeing.

This is what great art does. It doesn’t tell you what to think. It makes you notice that you’re thinking. And in a world where seeing too much often means feeling too little, Windows reminds us that sometimes, less really is more.

No comments yet.