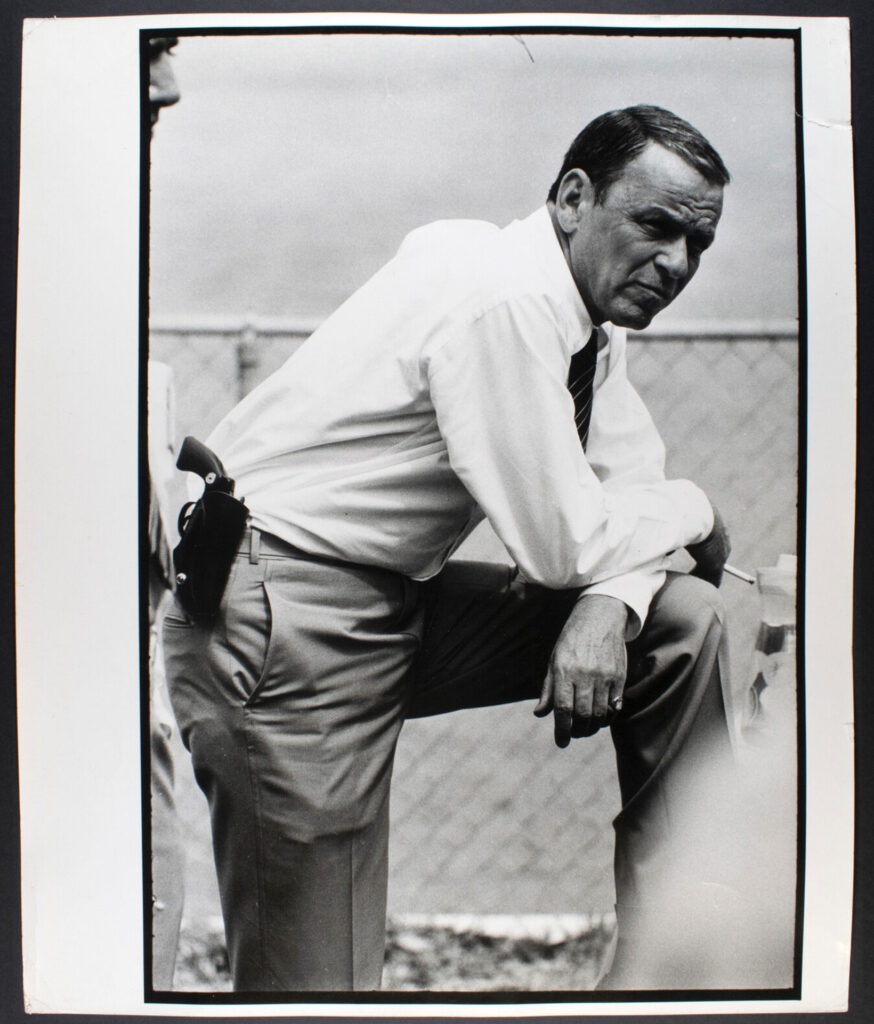

Terry O’Neill’s 1968 photograph of Frank Sinatra on the set of The Lady in Cement is not merely a celebrity portrait—it is an image that compresses cinema, myth, masculinity, and the mechanics of fame into a singular, crystalline moment. Captured in Miami during the height of Sinatra’s late-career film work, the original vintage print—distinguished by its provenance, tonal depth, and documentary resonance—functions as both artifact and atmosphere. More than a record of a film set, it’s a study in control, aura, and the invisible negotiations between public image and personal mythology.

THE SETTING: MIAMI, 1968—CINEMA IN HEAT AND HAZE

By 1968, Frank Sinatra was more than a performer. He was an institution. As a singer, he had reshaped the American ballad. As an actor, he had moved from musicals (Anchors Aweigh) and comedies to complex roles like The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) and Von Ryan’s Express (1965). But in The Lady in Cement, he was something else entirely: Tony Rome, a streetwise private eye traipsing through Florida’s sun-bleached mysteries.

Shot primarily in Miami, The Lady in Cement bathed noir tropes in tropics—beachfront bodies, pastel motel signage, convertible Cadillacs, and a casual violence veiled in nonchalance. It was in this context that Terry O’Neill—already established as one of Britain’s foremost celebrity photographers—stepped behind the lens to capture Sinatra not in concert halls or casinos, but amidst the manufactured chaos of a film shoot.

The Miami of 1968 wasn’t merely backdrop—it was a character of contradiction. Glamorous yet humid, luxurious yet vaguely dangerous, it matched Sinatra’s own dichotomies. And O’Neill’s photograph distills these contradictions perfectly.

THE COMPOSITION: POWER FRAMED IN MOTIONLESS CHARISMA

In the image, Sinatra is caught mid-stride—though the actual motion is immaterial. What matters is the arrangement. He is flanked by suited bodyguards, their postures not aggressive but alert, watchful. Behind them, extras and crew members fade into architectural noise. The sun is high, casting long shadows, but Sinatra remains the nucleus of the frame. Everything bends toward him in tone and temperature.

He wears a lightweight suit, open collar, hands at ease, and a fedora tilted just so. It’s a look not simply worn but lived—iconic without trying. He is not performing in this image. He is being. And therein lies O’Neill’s genius: the ability to photograph not a man, but a moment that performs him.

The vintage print quality—the grain, the gentle sepia of time, the filmic blur at the edges—adds depth not possible in modern digital retouching. One sees the sweat on linen, the texture of tarmac, the gleam on Sinatra’s sunglasses. This is analogue storytelling at its apex.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER: TERRY O’NEILL AND THE LANGUAGE OF LEGEND

Terry O’Neill was not merely a recorder of celebrity life; he was its interpreter. His images were intimate without being intrusive, posed without ever feeling staged. He had a singular ability to catch the liminal—those seconds between awareness and oblivion, between mask and face.

O’Neill photographed presidents and punks, Bond girls and Beatles, but his relationship with Sinatra stands out. Sinatra trusted him—an extraordinary rarity in an era where image control was sacred. The trust shows in the photograph’s relaxed intensity. There is no intrusion, no sense of journalistic detachment. O’Neill is in the world, but not of it. He sees but does not impose. His camera does not hunt; it reflects.

In later interviews, O’Neill spoke about the necessity of silence and smallness when photographing figures like Sinatra. You had to disappear. You had to know when to step forward and when to vanish. That balance of nearness and absence gives his 1968 print an almost cinematic gravity. One can feel the press of Miami heat, the electricity of industry, the sovereign force that was Sinatra.

SINATRA AS SYMBOL: MASCULINITY, MODERNITY, AND CONTROL

What makes this image endure is not just its craft but its myth. Sinatra here is not just a man walking on a movie set—he is an entire idea of 20th-century masculinity. Not muscle-bound, not boyish, but suave, lethal, and utterly in control. His power does not come from weaponry or posture. It comes from presence.

He moves through the world surrounded by aides and authority, but he is always the focal point. The camera confirms what the culture already believes: that Sinatra is the axis around which everything else orbits.

Yet, it’s not a domineering masculinity. There’s a poetic sadness at the edges. The sunglasses, the heat, the silent entourage—they also speak to isolation. Celebrity as enclosure. Performance as prison. And in 1968, as culture shifts—war, protest, counterculture movements—Sinatra represents a waning order. O’Neill captures that slight dissonance between power and aging relevancy. The man is mythic, but also temporal.

THE PRINT: MATERIALITY, PROCESS, AND VINTAGE AUTHENTICITY

To possess a vintage print of this image is to hold history. Printed by O’Neill himself or under his direct supervision shortly after the negative’s development, the vintage designation implies a tangible connection to the 1960s—not merely in content but in process. The silver gelatin paper, the traditional darkroom techniques, the subtleties of contrast and exposure—these cannot be duplicated by reprints or digital surrogates.

This is not just about collecting photography. It is about owning a slice of mid-century visual consciousness. A vintage print is imbued with physical time: the chemicals used, the air of the darkroom, even the imperfections of the enlarger. All of it partakes in the moment it depicts.

As with all of O’Neill’s works, provenance and edition size matter. Collectors covet these original pieces for their scarcity, but also for their aesthetic integrity. Unlike posters or mass-market reproductions, vintage prints retain the soul of the original moment. This photograph isn’t just seen—it’s experienced.

FILM AND PHOTOGRAPHY: A COLLISION OF NARRATIVES

The photograph does not compete with The Lady in Cement—it transcends it. While the film may be a curiosity in Sinatra’s cinematic canon, O’Neill’s image has outlived the movie’s critical lifespan. It renders the set eternal. The narrative of the film—murder mystery, underwater corpse, sixties cynicism—is merely a backdrop to the true drama: Sinatra’s existence in space, as interpreted by O’Neill.

There is an implicit dialogue between two mediums here. The film is structured, directed, scored. The photograph is ambient, unscored, and silent. Yet it communicates more. The irony is sharp: the movie needs 90 minutes and a script to make its case. O’Neill’s print needs only one frame.

THE IMAGE AS CULTURAL TEXT: POST-WAR AMERICA, FAME, AND THE AURA OF CONTROL

The photograph carries a deeper cultural burden. It is not just about a singer-actor or a set. It’s about a mythology that post-war America built around its men, its stars, its confidence. Sinatra, once the embodiment of World War II-era sentimentality, here becomes a figure of late-60s ambiguity.

The edges of control are fraying. Hollywood itself is shifting—Easy Rider, Bonnie and Clyde, and Midnight Cowboy are on the horizon. In this photograph, we see not just a performer but a style of masculinity soon to be challenged by countercultural softness, vulnerability, chaos. Sinatra’s calm is absolute, but it is also fossilizing. O’Neill captures the last flare before a generational eclipse.

Impression

Ultimately, Terry O’Neill’s 1968 vintage print of Frank Sinatra on the set of The Lady in Cement is more than a portrait—it is a climate. It speaks of who Sinatra was, but also of how history wanted to remember him. It’s a memory made visible, a performance of presence, a moment that now transcends its own origin.

It’s cinema without motion. Music without sound. Heat without sweat. And in every inch—grain, gesture, gaze—there is a quiet authority, whispering: This was a man, this was a moment, this was America as it wanted to be seen.

No comments yet.