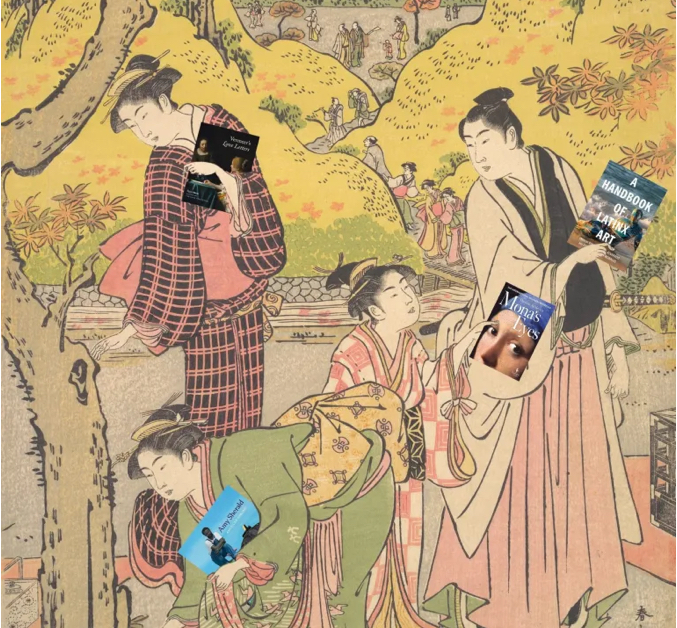

The caption is playful: “Even the figures in Katsukawa Shunchō’s 1789 woodblock print only buy from independent bookstores.” It’s paired with an image that’s over two centuries old—figures in elaborate robes browsing a shopfront scene, rendered in delicate lines and colors, with all the grace typical of the ukiyo-e tradition. The joke, of course, is modern—a wink to today’s pushback against Amazon’s cultural monopolies and a celebration of small bookstores as sanctuaries for the thoughtful.

But the resonance runs deeper. The humor gestures toward something timeless: the intimate, deeply human relationship between people and books, between local spaces and literary exchange. That this connection could be imagined across centuries, cultures, and languages suggests that the independent bookstore is more than just a business model—it’s a cultural archetype.

And Katsukawa Shunchō, whether he intended it or not, has become a symbol for it.

The Print in Context: Katsukawa Shunchō and the Floating World

Katsukawa Shunchō (active late 18th century) was a student of the legendary Katsukawa Shunshō, and a prominent figure in the ukiyo-e tradition—a genre of Japanese woodblock prints and paintings that flourished from the 17th to 19th centuries. Ukiyo-e translates loosely as “pictures of the floating world,” referring to the pleasure districts, tea houses, kabuki theaters, and marketplaces of Edo-period Japan (1603–1868).

Shunchō’s work often depicted women in domestic scenes or moments of social leisure—browsing, preparing tea, writing letters. The print in question, dated around 1789, shows a group of women in a bookshop or literary space. They lean toward books with gentle curiosity. The setting is intimate, refined, and saturated with calm.

At first glance, it’s a pretty slice of historical life. But look closer, and you see an ecosystem of cultural exchange. This was a time when literacy was rising, woodblock printing was booming, and the terakoya (temple schools) made reading a widespread practice across classes.

This wasn’t just a shop. It was a node in a cultural network.

The Bookstore as Cultural Infrastructure

The independent bookstore today functions similarly—not merely as a retail space but as a locus of identity, resistance, memory, and connection.

What makes bookstores like City Lights in San Francisco, Strand in New York, or Shakespeare and Company in Paris so enduring isn’t just their inventories. It’s their role as repositories of culture and sanctuaries for subversion.

Like Shunchō’s print, these spaces offer something beyond commerce. They offer a kind of social choreography: browsing, pausing, discovering. The possibility of encounter—not just with a book, but with an idea, a stranger, or even one’s own inner monologue.

This is not nostalgia. It’s structure.

The Public-Private Theater of Book Browsing

In Shunchō’s image, the act of reading is communal but quiet. The women gather in shared space but lose themselves in pages. There’s a balance between exposure and withdrawal, between being part of a moment and retreating from it.

This duality remains central to bookstore culture today. Walk into an independent shop and you enter a scene that’s semi-public, semi-private. You are on display—flipping through the poetry shelf, frowning at blurbs—but also cocooned in your own search.

There’s theater in it. Ritual. Permission to be selective, curious, even vulnerable.

Small Books, Big Ideas: The Bookstore as Intellectual Commons

Independent bookstores have always been intellectual accelerators. In postwar America, they were ground zero for Beat poetry, civil rights texts, and queer zines. In Latin America, they served as intellectual hubs during military dictatorships. In Tehran, Cairo, and Hong Kong today, they continue to function as subtle forms of dissent.

The smallness of the space allows for curation—and curation is a form of editorial politics. Unlike algorithmic recommendations, the tables in an indie shop are stocked by real humans with taste, values, and courage.

Just as Shunchō’s scene captures a curated world—where books are chosen, held, and shared—so too does the best of today’s book culture resist scale in favor of meaning.

Amazon, Algorithms, and the Assault on Serendipity

To contrast this with Amazon’s model is not merely to demonize scale. It’s to name a fundamental loss: the loss of the unplanned encounter.

Online algorithms reduce discovery to repetition. They predict based on what you’ve already done. In contrast, independent bookstores invite chance. You walk in looking for a memoir and leave with a field guide to moss. You bump into a former professor. You find your next obsession by accident.

Shunchō’s figures are not chasing efficiency. They are dwelling. They are suspended in the pleasure of the unknown.

That is what independent bookstores protect: serendipity.

Booksellers as Cultural Stewards

In many ways, the bookseller is the quiet protagonist of this ecosystem. Like the woodblock printer in Edo, today’s bookseller is part artisan, part curator, part therapist. They remember your name. They recall what you liked. They recommend a slim, odd little novel that changes your entire year.

Their work is not scalable. It is stubbornly analog. But it holds together the fabric of reading as a social act.

We don’t know who ran the shop in Shunchō’s print. But we can imagine them: sourcing texts, managing scrolls, gossiping gently, offering a wordless nod of approval as a customer lingered over a verse.

Some roles don’t change.

The Aesthetics of Book Space

The beauty of the print lies partly in its spatial composition. The architecture is open but defined. Shelves frame the scene. Scrolls and books hang in gentle disorder. It feels organic—like the best bookstores today.

A well-designed indie bookstore resists uniformity. It is a collage of eras and genres, of marginalia and mood. The design is not just aesthetic. It’s epistemological. It tells you how knowledge is organized. Or disorganized.

In this way, the bookstore becomes a philosophical space. You move through it not just to acquire, but to reflect. You rearrange yourself as you rearrange your understanding of what matters.

Why the Joke Works—and Why It Stings

“Even the figures in Katsukawa Shunchō’s 1789 woodblock print only buy from independent bookstores.”

It’s funny because it’s anachronistic. But it’s also funny because it’s true.

In a world where everything is designed for extraction—of data, of labor, of time—independent bookstores remind us of modes of existence that resist commodification. Shunchō’s scene, whether or not it shows a literal bookstore, captures that ethos.

The joke lands because the longing is real.

Impression

The ukiyo-e prints of the Edo period were known as “pictures of the floating world”—a phrase that captures transience, pleasure, and passing time. But within that floatingness was a kind of anchoring: to daily life, to community, to artistry.

Independent bookstores are our modern floating worlds. They are places where the ephemeral—words, thoughts, glances—becomes tangible. Where you walk in disoriented and walk out changed.

Katsukawa Shunchō didn’t know Amazon. But he knew how humans behave in spaces of care, curiosity, and quiet community.

That hasn’t changed in over 200 years.

No comments yet.