When we think about American independent cinema in the early 2000s, a particular constellation of films often comes to mind: Garden State, Lost in Translation, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But among this constellation, one film stands apart — not for its budget or its star power, but for the singular strangeness and warmth that radiated from its every awkward frame. That film is Napoleon Dynamite. Released in 2004, it quickly achieved cult status, turned a tiny Idaho town into a cinematic landmark, and reshaped the way studios approached marketing small, eccentric indie films.

At first glance, Napoleon Dynamite doesn’t appear to be a movie destined for cultural domination. Directed by Jared Hess and starring then-unknown Jon Heder, it told the story of a socially awkward high schooler navigating friendship, family, and an epic student body president campaign in rural Idaho. There were no A-list actors, no explosive set pieces, no sweeping romantic arcs. Yet, against all odds, Napoleon Dynamite not only earned over $46 million worldwide on a meager $400,000 budget but also pioneered marketing strategies that would ripple across the indie film industry for years to come.

A Movie Born from Peculiarity

To understand why Napoleon Dynamite resonated so deeply, one must first consider its origins. Jared Hess developed the character while studying film at Brigham Young University. In 2002, he and Jon Heder collaborated on a short film titled Peluca, which would become the seed for Napoleon Dynamite. The short was shot on black-and-white 16mm film over two days for around $500 — a testament to the DIY spirit that would define the final feature.

Hess’s script drew heavily from his own experiences growing up in Preston, Idaho, a rural farming community where teenagers often felt isolated and listless. The film’s visual style—muted, sun-bleached colors, static camera shots, and meticulously framed deadpan humor—evoked the sense of being stuck in a time warp. Viewers found themselves in a place where technology felt obsolete, fashion was decades out of date, and social dynamics moved at a glacial pace.

The movie’s characters—Napoleon, his brother Kip, their grandmother, and Pedro—were equal parts eccentric and endearing. Their peculiarities weren’t played for cruel laughs but rather highlighted the beauty and dignity of outsiders. Unlike many comedies of the time, which relied on slick quips and flashy editing, Napoleon Dynamite invited the audience into its awkward silences and earnest weirdness.

The Marketing Challenge

When Fox Searchlight picked up Napoleon Dynamite at Sundance in 2004, they faced a conundrum. How does one market a film with no big stars, no conventional plot, and a deeply idiosyncratic tone? The traditional approach—wide advertising blitzes, reliance on star interviews, and traditional press tours—seemed doomed to fail. The film needed a different touch, something as unexpected as the movie itself.

The answer lay in embracing grassroots, community-based marketing, essentially building a fan base from the ground up. Rather than chasing mainstream audiences immediately, Fox Searchlight focused on finding those who would become evangelists for the film, creating a ripple effect of word-of-mouth promotion.

Building a Social Network from Scratch

It’s almost quaint today to think of a time before social media dominated every aspect of film marketing. In 2004, MySpace was still finding its feet, Facebook was a college-only platform, and Twitter did not yet exist. Fox Searchlight’s team recognized the internet’s potential for niche communities but also understood that in-person engagement was still essential.

They began by orchestrating free screenings — hundreds of them. The logic was simple: if you could get the right audience in front of the film, they would do the rest. Screenings were held in college towns, small cities, and places that mirrored the film’s setting and spirit. These events were not traditional premieres with red carpets and media glare; instead, they were casual gatherings where audiences could discover the film organically, often with Heder or Hess in attendance to introduce the movie.

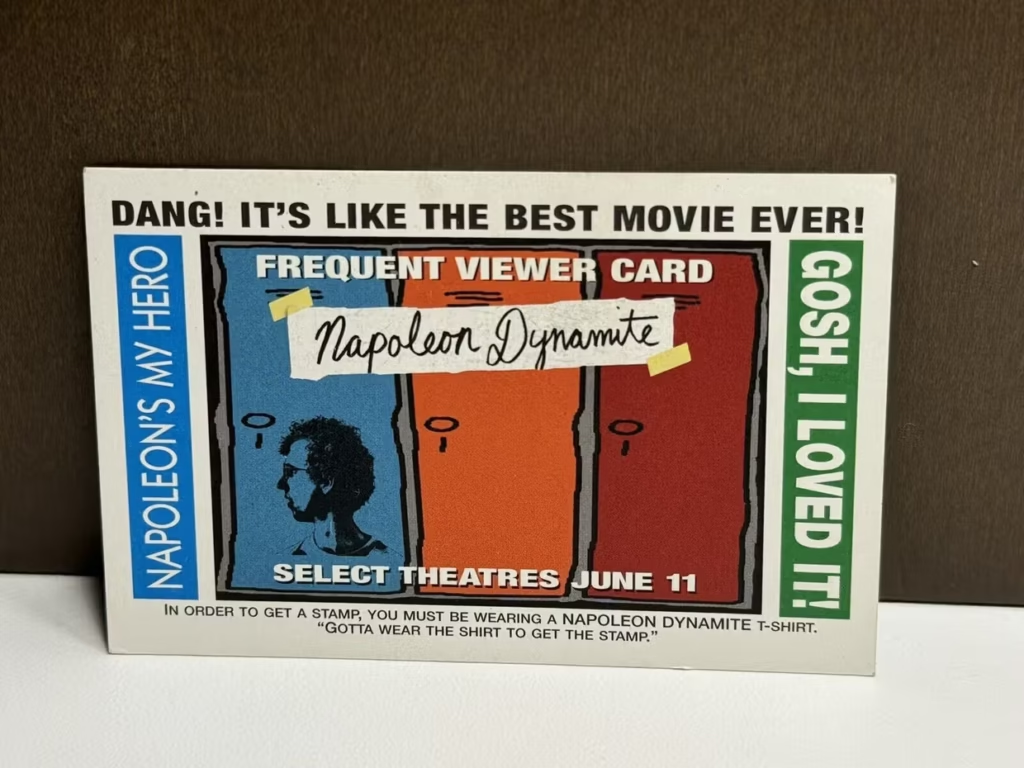

Beyond screenings, Fox Searchlight created an early version of what we might today call a “fandom hub.” They distributed “Vote for Pedro” T-shirts, stickers, and buttons. The shirts became especially iconic, turning up on campuses and at concerts across the country. This tactile approach helped people feel like they were part of an in-joke, a secret club bound by moon boots and tetherball.

Merchandise as Meme

The marketing team’s decision to focus on physical, wearable, and shareable items was ingenious. Instead of expensive TV spots, they turned the film’s symbols into viral marketing before “going viral” was common parlance. The “Vote for Pedro” slogan, originally a throwaway campaign line in the film, became a cultural touchstone. By the end of the summer, even people who hadn’t seen the film knew the reference. The slogan hinted at an inside joke that audiences could not resist being part of.

Merchandise extended to other quirky elements: Napoleon’s dance moves, his affinity for tater tots, and his love of ligers (“pretty much my favorite animal”). Fans recreated these references at parties and online, generating free publicity.

The Cult Phenomenon

Napoleon Dynamite debuted in June 2004 and slowly expanded from a handful of theaters to over 1,000 screens nationwide. Its box office climb mirrored its grassroots marketing strategy—slow, steady, and fueled by genuine enthusiasm rather than marketing dollars. The film grossed over $46 million globally, a staggering figure for a micro-budget indie feature.

Critics were divided, but for audiences, the film felt like a revelation. Its charm lay in its refusal to follow Hollywood conventions, and its marketing reflected this ethos perfectly. It wasn’t just that audiences liked the film; they felt ownership over it.

As DVD sales exploded in the mid-2000s, Napoleon Dynamite found a second life. Special features, deleted scenes, and commentary tracks helped deepen fans’ connection. Even today, the film continues to attract new generations of viewers who discover it through streaming platforms and meme culture.

The Broader Impression on Indie Marketing

The success of Napoleon Dynamite marked a turning point for indie film marketing. It demonstrated that for certain projects, building small but passionate communities could be more effective than large-scale campaigns. The approach prioritized authenticity over gloss, a concept that resonates more strongly than ever in today’s content-saturated environment.

In the years that followed, other indie films adopted similar tactics. Little Miss Sunshine (2006) and Juno (2007) also leaned into grassroots promotion, quirky merchandising, and fostering organic word-of-mouth. By the late 2000s, studios began to see value in “slow burn” releases, favoring staggered rollouts and carefully targeted festival circuits.

Simultaneously, as social media evolved, indie films increasingly tapped into online communities, creating official fan pages, running hashtag campaigns, and encouraging user-generated content. The seeds of these strategies were planted by Napoleon Dynamite’s humble, handmade approach.

Literature and Cultural Echoes

In literature and cultural studies, Napoleon Dynamite has been discussed as a text that captures the essence of “slacker” Americana — an echo of the Gen X aesthetic seen in Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1990) and Kevin Smith’s Clerks(1994). But unlike those earlier films, which focused on urban or suburban ennui, Napoleon Dynamite celebrated the rural and small-town peculiarities. Its aesthetic intentionally embraced awkwardness and nonconformity, reflecting a kind of rural magical realism.

Some scholars even argue that the film serves as a social critique of hyper-competitiveness and performative coolness that dominated early 2000s youth culture. Instead of polished teen heroes, we are offered a hero who is unapologetically uncool, who wins not through transformation but by sheer authenticity.

A Lasting Legacy

Twenty years later, Napoleon Dynamite’s influence is evident not just in indie film marketing but across broader pop culture. Characters like Napoleon, Kip, and Pedro have become archetypes for an entire genre of “awkward hero” narratives that continue in shows like Stranger Things and Pen15. The film’s spirit of DIY earnestness lives on in the explosion of low-budget web series, YouTube personalities, and TikTok creators who trade on authenticity over polish.

Even the marketing language of major studios has shifted to include more “authentic” voices, grassroots-style teaser drops, and direct fan engagement—all techniques pioneered, in part, by Napoleon Dynamite’s unusual campaign.

Recent Reappraisals

In recent years, critics and fans alike have revisited Napoleon Dynamite through the lens of nostalgia and changing cultural attitudes. With the rise of the “cringe comedy” genre and the embrace of outsider narratives, the film’s humor feels prescient. Meanwhile, the once niche, oddball aesthetic has become a mainstream style guide, influencing fashion (think of the resurgence of normcore), graphic design, and even political campaign strategies that borrow from the “Vote for Pedro” playbook.

The town of Preston, Idaho, now hosts an annual “Napoleon Dynamite Festival,” complete with tater tot eating contests and lookalike competitions. What began as a small local phenomenon has blossomed into an enduring part of American pop folklore.

Final

Napoleon Dynamite may have been a film about losers, but it turned out to be an astonishing winner — not just at the box office but in rewriting the indie marketing manual. By creating a social network before social media, by giving fans physical symbols of their devotion, and by trusting in the power of genuine word-of-mouth, it demonstrated that you don’t need Hollywood spectacle to create cultural impact. You just need a good story, earnest weirdness, and a community willing to share it.

In the summer of 2004, when Fox Searchlight set out to promote a quirky film about a teenage misfit in Idaho, they could hardly have predicted they were laying the foundation for a new era of film marketing. But two decades later, as brands and studios strive to build authenticity and cultivate micro-communities, the legacy of Napoleon Dynamite stands as a reminder: sometimes the best way forward is to let your freak flag fly — and invite others to fly it with you.

No comments yet.