There’s a moment — whether you’re five years old at a barbecue, seventeen in a sweaty gymnasium, or forty-three on a rooftop party — when the unmistakable bassline of “Get Down On It” cuts through the air like a groove you’ve known your whole life. And in many ways, you have.

Released in 1981, Get Down On It by Kool & The Gang is more than just a funk track. It’s an institution of rhythm, a generational handshake, a ritual call to dance passed from cassette decks to Spotify playlists, from vinyl grooves to TikTok choreography. It’s not just heard — it’s felt, in knees that bend instinctively, in hips that catch the pocket, in smiles exchanged as someone mouths the words: “What you gonna do? Do you wanna get down?”

But beneath its celebratory exterior, Get Down On It tells a larger story — about the cultural optimism of post-disco America, about Black joy as defiance and resilience, about the genre-fluid genius of Kool & The Gang themselves. In revisiting the track today, we honor not just a song, but a sonic archive of joy — one that refuses to be forgotten or boxed into nostalgia.

The Groove That Won’t Quit

To appreciate the impact of Get Down On It, you have to first understand its design. Produced by Eumir Deodato, the track strikes a balance between tight funk instrumentation, radio-friendly polish, and a repeating lyrical mantra that embeds itself in the cultural memory.

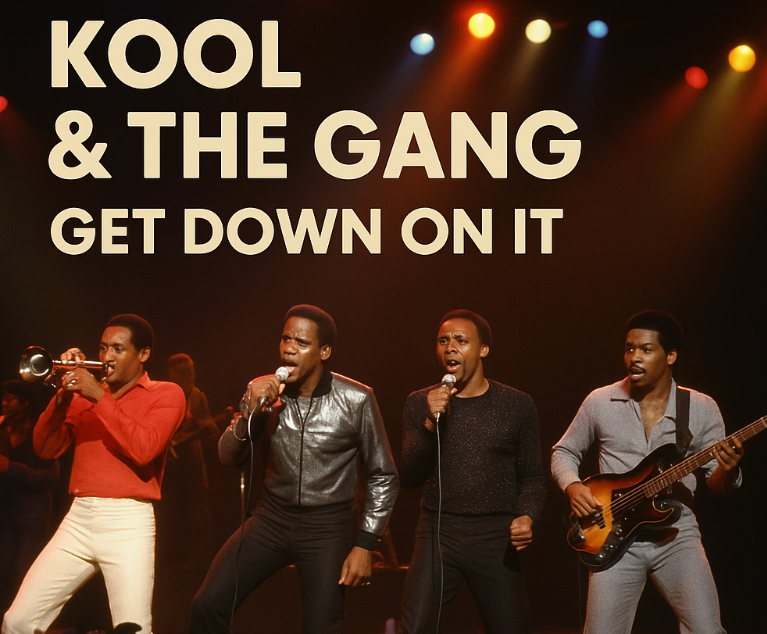

The song opens with a bassline that feels part Earth, Wind & Fire, part Chic, and entirely Kool & The Gang — a band that had, by this point, mastered the ability to combine jazz roots, R&B flair, and pop structure. The brass section punches in with signature efficiency. The vocals, led by James “J.T.” Taylor, don’t command so much as they invite.

“How you gonna do it if you really don’t wanna dance, by standing on the wall?”

That lyric, deceptively simple, becomes a kind of democratic mantra. The wall here is literal and metaphorical — a metaphor for hesitation, for social paralysis, for staying on the sidelines of your own joy. The track becomes a ritual of participation, urging everyone to join the movement — not just to dance, but to live fully.

And then comes the hook — “Get down on it” — repeated with percussive insistence, backed by funk guitar jabs, percolating synth stabs, and a tempo that pushes just fast enough to energize without exhausting.

1981: A Cultural Context of Transition

Get Down On It was released at a complicated cultural moment. Disco, once the dominant sound of the late 1970s, had suffered the backlash of the “Disco Sucks” movement — an ugly collision of racism, homophobia, and rockist conservatism disguised as musical taste. Dance music, particularly when tied to Black and queer communities, had been scapegoated in the mainstream. Labels scrambled to rebrand.

But Kool & The Gang, having survived the shifts from jazz fusion to soul to funk, saw in this moment not decline but opportunity. Rather than abandon the dancefloor, they doubled down on it — crafting a track that honored disco’s celebratory DNA while embracing funk’s muscular rhythm and pop’s sing-along accessibility.

This was also the Reagan era, a time of economic uncertainty masked by conservative glamour. The dancefloor, particularly for marginalized communities, remained a sacred space — a place to process, resist, and reclaim joy. “Get Down On It” wasn’t escapism. It was resistance wrapped in rhythm.

Historicism and the Ethics of the Groove

In examining Get Down On It through a historicist lens, we see it as part of a larger cultural continuum of Black expressive music. From gospel’s call-and-response to James Brown’s command of syncopation, from the disco anthems of Donna Summer to the pre-hip-hop party records of The Sugarhill Gang, Kool & The Gang stands at the intersection of lineage and innovation.

They didn’t invent the groove. But they perfected its accessibility — crafting music that invited mass participation without diluting its roots. In doing so, they preserved a key African American tradition: the groove as collective ceremony, as embodied community.

Funk, after all, is historical memory you can dance to. It’s not just about “feel-good music” — it’s about the right to feel good in a world that doesn’t always permit it. The right to move, even when the system wants you stuck. Kool & The Gang’s chorus becomes a historical challenge: “What you gonna do?” It’s not just a party prompt — it’s a question of presence, of purpose, of liberation.

The Band That Did Everything, Quietly

Part of the legacy of Get Down On It rests in how understated Kool & The Gang’s genius was. While other acts chased spotlight reinvention or dramatic style shifts, Kool & The Gang evolved organically, moving from jazz innovators in the late ’60s to R&B chart toppers, to party-starters with near-universal appeal.

Their lineup was a democracy of sound — built around Robert “Kool” Bell’s anchoring bass, George Brown’s precision drums, Ronald Bell’s sax and arrangements, and later, the vocal charisma of J.T. Taylor. There were no egos leading the charge. There was unity — musical, ideological, and rhythmic.

When they shifted toward more commercial R&B in the late ’70s, critics worried they’d sold out. But time has shown that Kool & The Gang were simply ahead of their time, understanding that survival in music means adaptation — not at the expense of identity, but in celebration of it.

“Get Down On It” is not just catchy. It’s meticulously crafted. It’s harmonically tight, lyrically intentional, and structurally durable. You can strip it down to bass and drums and it still hits. You can orchestrate it with strings and brass and it soars.

Legacy Through Repetition: The Echoes of “Get Down On It”

One mark of a classic is how often it’s quoted, sampled, covered, or interpolated. “Get Down On It” has been all of the above.

- Snoop Dogg and Jermaine Dupri flipped it in 2004 for “Bounce, Rock, Skate,” turning its funk into G-funk nostalgia.

- Blue, the British boyband, covered it in 2004 with Kool & The Gang themselves — introducing the track to a new European audience.

- DJs across house, disco, and pop genres still drop it mid-set, using it as a social reset button — a guarantee that bodies will move and hearts will lift.

Beyond explicit covers, the feel of “Get Down On It” is embedded in decades of groove-centric pop: from Bruno Mars’s retro revivalism to Daft Punk’s love letter to disco-funk. And in dance circles — whether it’s roller skating rinks, weddings, or TikTok montages — it endures as unironic, unfiltered joy.

Intergenerational Rhythms: A Living Archive

There’s something magical about watching people who weren’t alive in 1981 move instinctively to Get Down On It. Children do it. Teenagers do it. Grandparents mouth the lyrics like they never left the club.

This speaks to the song’s intergenerational function. It’s not just a hit. It’s a rite of passage. A loop passed down through families, across oceans, through language and fashion and changing sound systems.

This is historicism in action — not a dusty textbook, but a living groove, one that transforms memory into movement.

No comments yet.