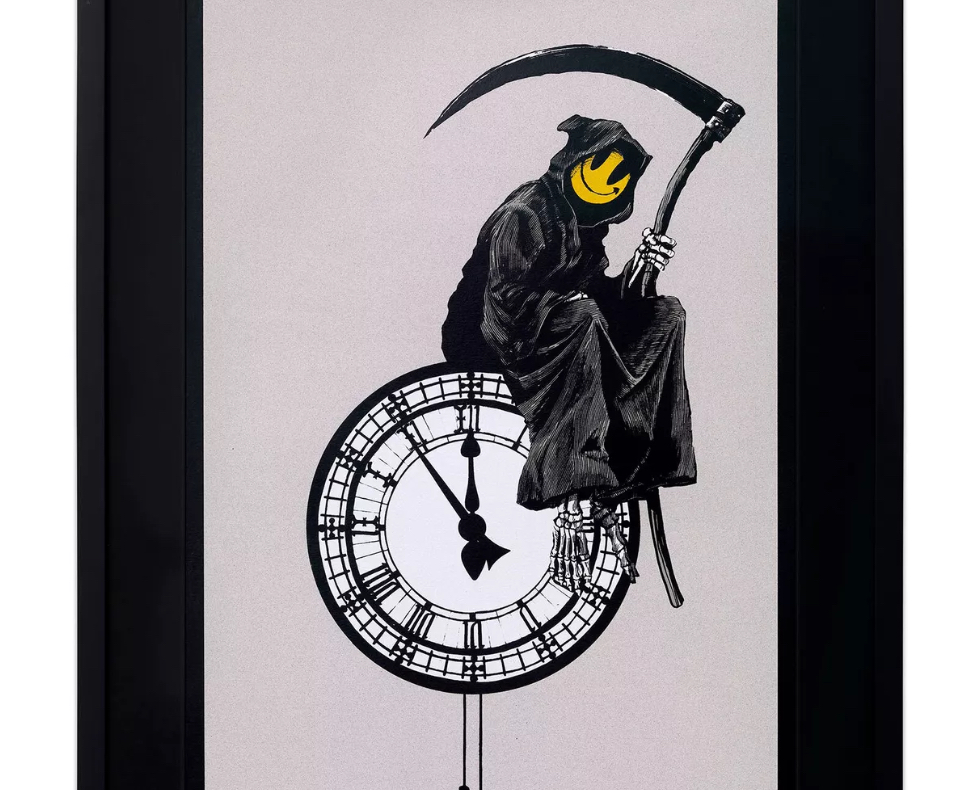

In the world of street art, few figures carry the cultural heft—or mystery—of Banksy, the anonymous British provocateur whose works challenge systems of power, poke holes in institutional sanctity, and often deploy absurdist wit in the face of serious subject matter. Among his most striking—and enduring—creations is Grin Reaper (2005), a black-and-white screen print that fuses macabre iconography with pop cultural levity. Here, death wears a grin. And yet, the smile—stolen from the ubiquitous smiley face emblem of British rave culture—is anything but comforting.

More than a clever graphic, Grin Reaper represents the meeting point of social commentary, subcultural reference, and existential memento mori. Printed on paper, in a medium long favored for its reproducibility and activist potential, the image functions as both artwork and artifact—pointing us toward the edges of life, laughter, and rebellion.

The Composition: Smiling Death with a Scythe

At first glance, Grin Reaper is startling in its stark contrast and simplicity. Rendered in black-and-white screen print, the figure is unmistakably the Grim Reaper—shrouded in a hooded cloak, holding a scythe in one bony hand. But instead of the skeletal face we’ve come to expect from centuries of death depictions, this Reaper wears a bright yellow smiley face—the icon that came to represent optimism, consumer joy, and the UK’s acid house movement in the 1980s and 90s.

This collision of symbols is classic Banksy: death and joy, fear and absurdity, coexist in the same frame. The image is cropped tightly, giving it the immediacy of a warning sign. But there is no text. No slogan. Just a contradiction so visually potent it doesn’t need explanation.

Medium and Multiplicity: Art for Everyone (and No One)

Grin Reaper was released as a screen print, a choice that carries its own conceptual weight. Banksy, ever suspicious of elite art markets, has used screen printing throughout his career to democratize access to his work—while simultaneously critiquing the very mechanisms through which art is commodified.

The 2005 edition of Grin Reaper was printed by Pictures on Walls (POW), Banksy’s own distribution outfit that sold affordable prints directly to the public. The print run included both unsigned and signed editions—roughly 300 signed and 600 unsigned—further complicating the work’s relationship to value, scarcity, and authenticity. In a world where collectors obsess over provenance, Banksy’s editions function as bait and switch: high-concept art masquerading as lowbrow poster fodder.

And yet, despite this posture, Grin Reaper has become a sought-after piece in the secondary market. Prices for signed editions now exceed six figures at auction—proof, perhaps, that even the most anti-commercial gestures are not immune to commercial digestion.

Death, Detournement, and Dance Culture

To understand the deeper impact of Grin Reaper, one must consider the cultural context of the smiley face. Originally designed by Harvey Ball in 1963 as part of a morale campaign, the image was later co-opted by advertising and then reclaimed again in the 1980s by the UK rave scene. As the face of acid house and techno subculture, it appeared on flyers, album covers, and t-shirts—symbolizing not only euphoria but defiance.

In this light, Banksy’s smiley-faced Reaper isn’t just ironic—it’s layered. It suggests that even the most rebellious signs can become hollow, commercialized, or reabsorbed into the machinery of culture. The once-radical smiley is now worn by death, who wields it like a mask. What was once the face of youth freedom is now just another tool of inevitability.

This speaks to Banksy’s broader critique of late capitalism’s ability to consume everything—from symbols of dissent to the concept of death itself. In Grin Reaper, mortality isn’t feared. It’s branded.

Memento Mori and Pop Irony

Art history is littered with memento mori—reminders of death embedded within otherwise mundane or luxurious scenes. From skulls in Dutch still lifes to the vanitas genre’s rotting fruit and extinguished candles, artists have long inserted symbols of mortality to remind viewers of life’s impermanence.

Banksy continues this tradition but rewires it for the media-saturated 21st century. Grin Reaper is a memento mori for a generation raised on rave culture, irony, and political disenchantment. It’s not about quiet contemplation—it’s about visual confrontation. The skull is gone. In its place, a grin that may or may not be sincere.

There’s humor here, of course—but it’s laced with anxiety. Who is death smiling at? Is this our companion or our executioner? Is the joke on death—or on us?

The Anti-Institutional Edge

Banksy’s artwork has always existed in tension with art world norms. Though widely collected and critically discussed, his work consistently points back to the hypocrisies of the system that props him up. Grin Reaper participates in this critique through form and theme.

By choosing screen print—a method associated with protest posters and DIY zines—Banksy positions himself alongside countercultural movements, not blue-chip galleries. And by choosing the Reaper—a symbol of universal fear—he suggests that no one, not even the art world, escapes the inevitable.

Indeed, the print’s accessibility has led to copies appearing in homes, dorms, tattoo shops, and galleries alike. Unlike unique canvases, Grin Reaper circulates. It spreads. It replicates. And in that sense, it refuses to be caged.

A Mirror to the Viewer

As with much of Banksy’s work, Grin Reaper also functions as a mirror. The viewer is forced to reconcile the dualities embedded in the image: life and death, humor and dread, rebellion and conformity.

Are we laughing with the Reaper? Or trying to laugh at him, to disarm our own fear?

The ambiguity is where the power lies. Banksy doesn’t offer moral clarity. Instead, he offers confrontation. You come to the work expecting clarity—and leave with contradiction.

Relevance and Reemergence

Though released in 2005, Grin Reaper feels just as relevant—if not more so—today. In an age of global instability, pandemic trauma, and digital burnout, the line between humor and horror is thinner than ever.

The Reaper’s smile reads differently now. It isn’t just ironic—it’s uncanny. A false reassurance. A cartoon face pasted over a real threat. In a way, the image predicts how public messaging has evolved: the tendency to anesthetize crisis with memes, slogans, and campaigns that soothe more than solve.

Grin Reaper endures because it refuses to resolve. It’s a sign of death that winks back.

Impression

Banksy’s Grin Reaper is deceptively simple: a figure of death holding a scythe, wearing a grin. But within this minimalism lies a complex network of critique, symbol, and cultural reflection.

It is a work that laughs at power while recognizing its pervasiveness. It’s a challenge to the commodification of rebellion, the emptiness of overused symbols, and the viewer’s own relationship with fear and pleasure. It fits in bedrooms and museums, subcultures and Sotheby’s.

No comments yet.