The Season of Fear

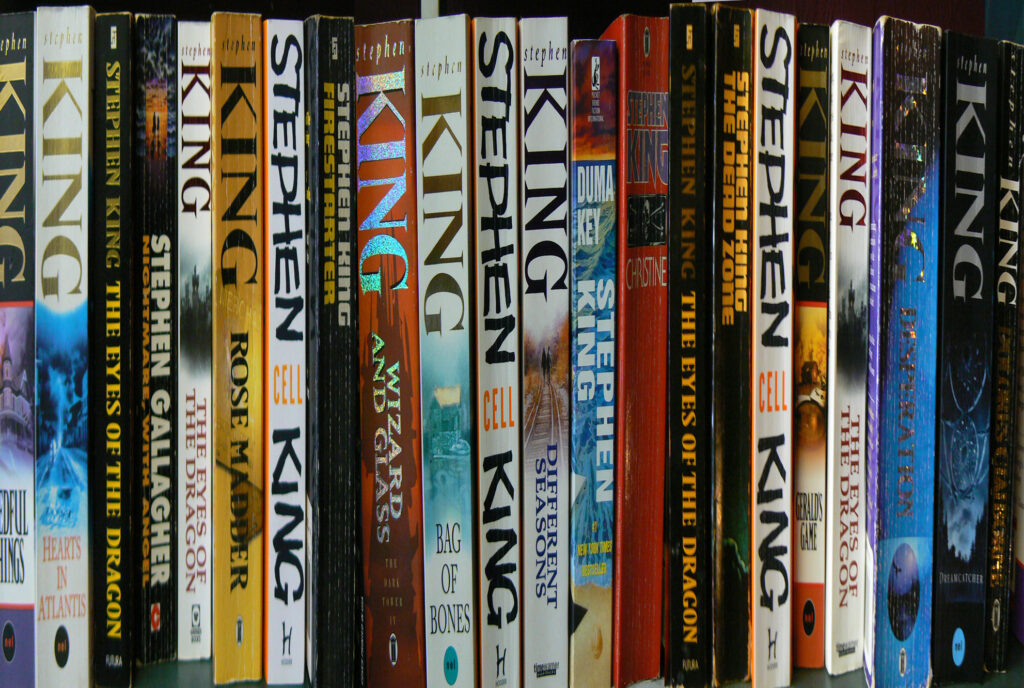

October has long belonged to Stephen King. His novels sit at the heart of America’s Halloween ritual—dog-eared paperbacks stacked beside pumpkin-scented candles, TV marathons of It and The Shining flickering on screen, teenagers daring each other to read Pet Sematary in one sitting. But this spooky season, the King of Horror finds himself in a role no author covets: the most banned writer in US schools.

According to PEN America’s 2025 report on educational censorship, King’s works faced 206 formal challenges in the 2024–2025 school year. In total, 6,800 bans affected 3,752 unique titles, most clustered in Florida, Texas, and Tennessee—states where legislators have codified or encouraged aggressive book challenges.

The irony is macabre but fitting: the man whose career was built on stories of haunted hotels, cursed towns, and vengeful outsiders now finds his own books exorcised from classrooms and libraries, cast out by committees fearing contamination.

The Numbers: A Shrinking But Intensifying Wave

The PEN America report shows a decline in overall bans from the year before—10,000 down to 6,800—but warns that the numbers still dwarf pre-2020 levels. For comparison, fewer than 300 bans were tracked annually just a decade ago.

A striking 80% of challenges originated in three states. Florida, Texas, and Tennessee have become laboratories for new censorship laws. Some statutes allow parents to demand immediate removal of any book they object to. Others empower state officials to publish “approved lists” that exclude thousands of contemporary works.

The targets are predictable but revealing: titles addressing LGBTQ+ identity, racial history, reproductive health, and sexual violence. Horror fiction, though not usually at the top of the list, becomes vulnerable when it veers into blood-soaked terrain. King’s novels, with their unflinching depictions of abuse, addiction, bullying, and brutality, offer plenty of material for censors to seize upon.

King’s Library of the Damned

The specific novels challenged vary by district, but certain titles repeatedly surface:

-

Carrie (1974), King’s debut, featuring teenage blood, religious fanaticism, and telekinetic revenge.

-

It (1986), sprawling and profane, with graphic violence and scenes of childhood trauma.

-

The Shining (1977), where alcoholism, madness, and domestic violence permeate the Overlook Hotel.

-

Different Seasons (1982), a novella collection including The Body (basis for Stand by Me) and Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, both less horrific but rich in profanity and depictions of violence.

Some challenges cite occult themes or graphic scenes. Others vaguely invoke “age inappropriateness.” Yet King’s books have been staples of school curricula for decades, praised for accessible prose, cultural resonance, and capacity to hook reluctant readers.

The paradox: many students’ first “big” novel is a Stephen King paperback borrowed from a school library. By banning him, districts may be shutting the very door through which a generation could walk into serious reading.

Why King? Symbol, Not Just Substance

Part of King’s status as the most banned author may be statistical coincidence—he’s prolific, with over 65 novels and 200 short stories in circulation. The sheer volume increases the odds of challenges.

But symbolically, King embodies a cultural fault line. He’s both populist and literary, mainstream yet transgressive. His novels sell by the millions and inspire Hollywood blockbusters, but they also dwell obsessively on taboo subjects: abusive parents, predatory authority figures, children facing monstrous realities adults refuse to acknowledge.

For school boards bent on sanitizing reading lists, King’s fiction represents a double threat. It’s not niche or avant-garde—it’s accessible, familiar, woven into American childhood. To remove him is to police not only content but nostalgia, rewriting the canon of late-20th-century popular culture.

Horror as Social Commentary

Critics often underestimate King’s genre, reducing him to gore and ghosts. Yet his horror is social allegory. Carrie is about misogyny and religious repression. It chronicles systemic evil in a small town, from racism to child abuse, long before Pennywise appears. The Stand wrestles with pandemics, authoritarianism, and moral collapse.

In this sense, banning King echoes the broader trend of targeting books for addressing systemic inequality. Just as The Bluest Eye (Toni Morrison) or Gender Queer (Maia Kobabe) draw fire for depicting difficult truths, so do King’s stories—albeit in supernatural guise. The horror is less the monster than the society that creates it.

That’s precisely what unsettles censors. Horror fiction dares to admit what polite civics lessons obscure: cruelty, prejudice, and violence lurk in ordinary homes, schools, and churches.

The Three States of Fear: Florida, Texas, Tennessee

The concentration of bans in Florida, Texas, and Tennessee is no accident.

-

Florida: The “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” and related measures incentivize challenges to books on race and sexuality. Governor Ron DeSantis’s administration has championed parent-driven reviews of library holdings, creating a chilling effect.

-

Texas: Lawmakers proposed blacklists of “sexually explicit” titles, leading to wholesale removals of YA fiction, graphic novels, and even classics like Of Mice and Men.

-

Tennessee: The 2022 “Age-Appropriate Materials Act” triggered high-profile removals, including Maus (Art Spiegelman). King’s violent depictions fall within this expanding dragnet.

In each state, censorship is not just cultural but political—mobilized as part of campaigns around parental rights, curriculum control, and “protecting children.” King’s works, by virtue of their ubiquity, become easy trophies in this war.

The Legacy of American Book Bans

Censorship is not new. From Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn to J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, American classrooms have long policed literature. What distinguishes the current wave is scale and coordination. National advocacy groups now publish lists of “objectionable” titles. Local activists, empowered by state law, can challenge dozens of books at once.

This is less a handful of parents quarreling over Harry Potter than a systemic effort to reshape public education. Within this framework, King’s removal is not incidental but emblematic—proof that even mainstream cultural icons are vulnerable.

King Speaks Back

Stephen King has never been shy about politics. On social media, he frequently criticizes right-wing lawmakers and defends freedom of expression. In response to past bans, he’s urged students to “go find the books yourselves—read what they don’t want you to read.”

His advocacy resonates with his own biography. Raised by a single mother in working-class Maine, King grew up on pulp magazines and cheap paperbacks scavenged from thrift stores. The library was his lifeline. To see libraries emptied of his books is, for King, a return to the dystopias he imagined—societies where authority erases stories to control reality.

The Cost to Students

The debate is often framed in abstract terms—parents’ rights, community standards, free speech. But the human impression is concrete. For many teenagers, a Stephen King novel is their first brush with literature that acknowledges their fear, anger, or trauma.

When Carrie is banned, what happens to the bullied girl searching for a mirror of her rage? When It is removed, what happens to the boy confronting abuse at home? These books may be fantastical, but their resonance is painfully real. By erasing them, schools risk erasing the students who see themselves within the pages.

Spooky Season Without Stephen King?

There is irony, even comedy, in the timing. As Halloween approaches, bookstores display King’s covers like jack-o’-lanterns. Hollywood continues to adapt his works—Salem’s Lot is slated for a new film version, The Outsider recently drew HBO acclaim. Yet in school libraries, shelves may stand empty where his novels once lived.

This disconnect illustrates the broader absurdity of book bans. Outside the schoolhouse, King’s works are impossible to escape—on streaming platforms, in grocery-store paperback racks, in the collective imagination. Removing them from libraries is less about shielding children than signaling ideological control.

A Haunted Future?

The PEN America report warns that while overall bans dipped, the movement is evolving, finding new footholds in law and policy. Unless challenged, the coming years may see sustained pressure to standardize “safe” reading lists across entire states.

For horror fans, the metaphor writes itself. The bans spread like a viral contagion, or a shape-shifting monster: fewer in number, but more cunning, more organized, harder to kill. The question is whether communities will resist—or resign themselves to living in the cultural equivalent of a haunted house, where the scariest thing isn’t the ghost in the closet, but the silence where a book used to be.

Impression

Stephen King once wrote, “Books are a uniquely portable magic.” In 2025, that magic is under siege. Yet the very act of banning him proves the enduring power of his stories. To frighten a censor is, after all, the ultimate achievement for a horror writer.

In the end, the bans say less about King than about the America attempting to silence him. A nation afraid of its own children’s curiosity has chosen to wage war not against monsters, but against books. And like all of King’s villains, such fear cannot be vanquished by erasure. It festers in the dark—until someone dares to open the door, and read.

No comments yet.