A Plasticine Palimpsest

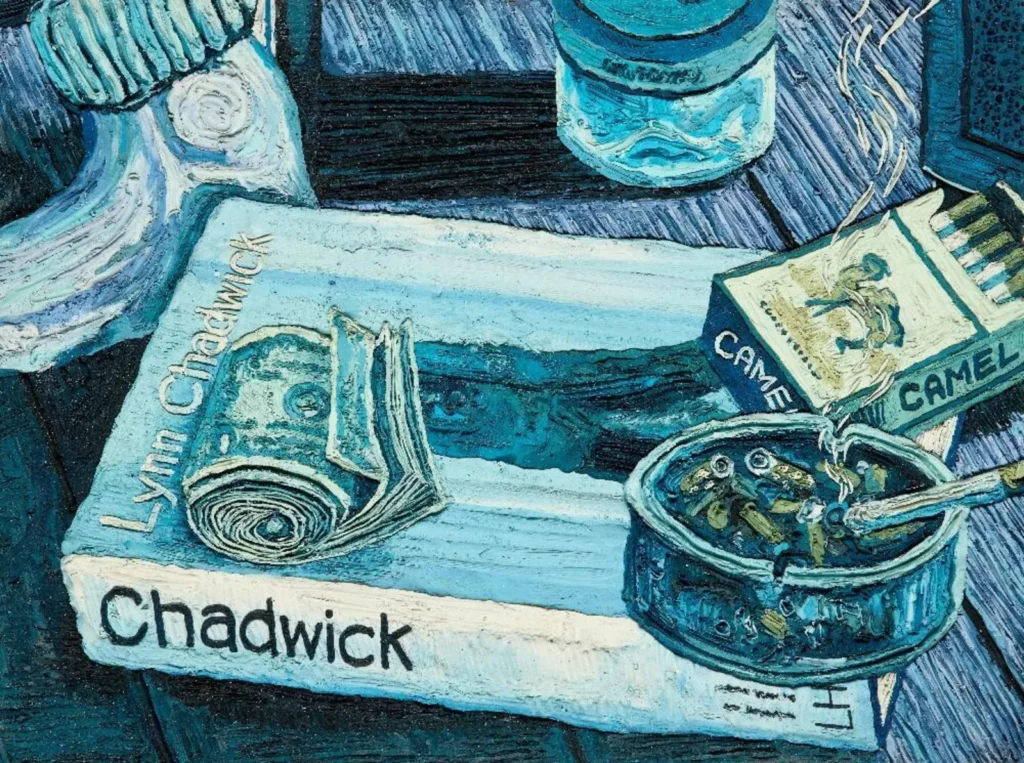

Henry Hudson’s Untitled (Chadwick) is not a quiet artwork. Even in reproduction, its surface almost seems to hum with energy, thick with ridges and grooves of hand-molded plasticine. At first glance, it reads as a still life: a tabletop scattered with familiar items—a monograph on the sculptor Lynn Chadwick, a pack of Camel cigarettes, a glass of water, an overflowing ashtray, rolled bills of money. Yet nothing about this painting, if one dares call it that, is conventional. The materials are sculptural, not painterly. The subject matter hovers between banality and symbolism. And the execution feels at once contemporary and strangely archaic, recalling Van Gogh’s tactile surfaces or Morandi’s contemplative still lifes, but rendered in the synthetic sheen of petroleum-based clay.

To unpack Untitled (Chadwick) is to move through layers: medium, composition, cultural context, and its place within Hudson’s larger project of cataloging modern life. Like much of his work, it is less about the items themselves than what they signify in the fragile economy of attention, addiction, and art.

The Medium: Plasticine as Rebellion

Hudson has made plasticine his signature medium, and here it is deployed with all its stubborn physicality. Unlike oil paint, which can be thinned, blended, and layered to transparency, plasticine insists on presence. Every mark is a ridge, every gesture is fossilized in waxy permanence.

The choice is significant. Plasticine is not noble. It is not archival in the traditional sense. It is cheap, associated with childhood play rather than fine art. Yet Hudson elevates it, forcing the viewer to confront its sensual immediacy. The swirls of blue and teal mimic brushstrokes, but their three-dimensionality reminds us this is not illusion but accumulation. The medium itself becomes commentary: on artificiality, on disposability, on the persistence of the synthetic in our daily lives.

In Untitled (Chadwick), this material choice doubles the irony. The book on Lynn Chadwick—an artist celebrated for his metal sculptures, often sharp-edged and monumental—is here rendered in a soft, malleable, and resolutely modern clay. Where Chadwick worked with permanence, Hudson works with impermanence. The juxtaposition feels intentional, almost mischievous.

The Composition: Still Life or Cultural Autopsy?

Laid across the tabletop are items that could be read as mere ephemera: cigarettes, ashtray, money, a drink. Yet their arrangement suggests something more deliberate.

The book anchors the composition. Its title, “Chadwick,” is both a name and a weight. It references a figure in the history of British sculpture, but also acts as a block of text within the image, an object of language. On top of it rests a roll of cash, its circular form contrasting with the rectangular solidity of the book. Currency and culture, commerce and art, stacked together.

To the right, the Camel cigarette pack bursts open, its letters half-visible, almost sculptural in themselves. A lit cigarette smolders, its smoke rendered in curling streaks of plasticine. The ashtray brims with spent butts, rendered with grotesque thickness, each stub a miniature sculpture of waste. Behind it, a glass of water—its transparency ironically opaque in plasticine form—catches the light.

The composition is tight, cropped as though captured by a camera phone. There is no depth of field, no horizon line. Instead, the viewer is forced into intimacy, into confrontation with the objects. It is a portrait without a body, a character study through possessions.

Symbolism: Consumption and the Everyday

Each object in Untitled (Chadwick) carries symbolic weight.

-

The cigarettes evoke addiction, ritual, mortality. Their brand, Camel, carries a cultural history: soldiers in wartime, rugged masculinity, an era when smoking was glamour rather than taboo.

-

The ashtray, overflowing, suggests excess and aftermath. It is less about the pleasure of smoking than its residue, the debris of consumption.

-

The rolled bills signify both wealth and waste, money folded not into savings but into casual display.

-

The glass of water—seemingly benign—contrasts with the toxicity of cigarettes, yet in its banal clarity it also feels insufficient, an afterthought.

-

The Chadwick book places this personal clutter against the backdrop of high art history, reminding the viewer that creativity is always lived in tension with the mundane.

Hudson transforms these objects into cultural hieroglyphs. They speak less about individual identity than about a collective condition: a society oscillating between cultural aspiration (the monograph) and everyday compulsion (the cigarettes, the money, the clutter).

Art Historical Context: Still Life, Revisited

Still life has long been the genre through which artists interrogate material culture. From the vanitas paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, where skulls and rotting fruit reminded viewers of mortality, to Cézanne’s apples and bottles, to Warhol’s Brillo boxes, the everyday has been repeatedly elevated as a site of artistic meaning.

Hudson’s contribution lies in his choice of medium and subject. By using plasticine, he both honors and undermines this lineage. His works echo the tactile urgency of Van Gogh, yet their surface is synthetic, unyielding, non-biodegradable. Where vanitas paintings dwelled on the decay of organic matter, Hudson dwells on the persistence of the inorganic. Cigarettes turn to ash, but plasticine remains. Money circulates, but the molded roll of clay will never unspool.

In this sense, Untitled (Chadwick) functions as a contemporary vanitas. Its subject is not just mortality, but consumption and permanence: the permanence of the synthetic, the permanence of the waste we leave behind.

Henry Hudson’s Practice: Cataloguing the Now

This work is not an isolated gesture. Hudson has repeatedly explored the aesthetics of daily detritus. His “tabletop” compositions act as archaeological sites of the present, excavations of cultural residue. By fixing these objects in plasticine, he resists their transience. What would normally be swept away—the cigarette butt, the half-drunk glass of water, the receipt—is monumentalized.

Hudson’s practice can be read as both affectionate and accusatory. There is humor in the elevation of the banal, but also critique: of consumer culture, of addiction, of the way we clutter our lives with symbols of status and self-destruction. His work is not romantic, yet it is not nihilistic either. It acknowledges that meaning resides in these objects because we place it there.

Lynn Chadwick: A Ghost in the Work

Why Chadwick? The inclusion of the sculptor’s name is not incidental. Lynn Chadwick (1914–2003) was known for his angular, often menacing figures, sculptures that seemed to fuse man, beast, and machine. His work was heavy, sharp, industrial.

Hudson’s invocation of Chadwick functions on several levels. It is homage, situating himself within a lineage of British sculptural practice. But it is also contrast: Chadwick’s permanence versus Hudson’s impermanence, steel versus clay, monumental versus miniature. To place Chadwick’s name beneath cigarettes and cash is to stage a collision between cultural aspiration and cultural reality.

The book in the painting might be read as a kind of talisman, a reminder that even as we live amidst clutter and consumption, the history of art remains a grounding force. Or perhaps it is ironic: art reduced to another object in the mess of modern life.

The Aesthetics of Blue

The chromatic palette of Untitled (Chadwick) is dominated by blues: pale, teal, navy. This is not a naturalistic rendering of the tabletop but a deliberate chromatic filtering.

Blue carries symbolic weight. It is the color of melancholy, of cool detachment, of midnight reflections. It is also the color of water and of corporate branding, of stability and sterility. In Hudson’s hands, blue becomes a unifying tone that both aestheticizes and distances. The objects lose their immediate familiarity; they are transposed into a dreamlike register, a nocturnal memory rather than a direct depiction.

The effect is striking: the ashtray and cigarettes, usually symbols of warmth and fire, are rendered cold. Money, usually green, is instead icy. Even the Chadwick book feels submerged. It is as if the entire scene is frozen under a sheet of glass or viewed through a haze of smoke.

The Politics of Plasticine

Hudson’s use of plasticine cannot be divorced from environmental politics. Plasticine, a petroleum product, is a symbol of the Anthropocene: durable, artificial, destined to outlive organic matter. In choosing this medium, Hudson implicates himself and his audience in questions of sustainability and permanence.

The cigarette butts, sculpted in plasticine, will never decompose. The money, frozen in clay, will never be spent. The water, once drinkable, is now a simulacrum. The entire scene is a museum of uselessness, preserved forever in petrochemical material.

This irony sharpens the critique: what we consume, what we discard, what we value—all are locked into a cycle of synthetic permanence. Hudson’s work does not preach, but it insists we confront this dissonance.

Reception and Interpretation

Critics have noted Hudson’s unusual position in contemporary art. He is both traditional—working in a tactile medium, reviving still life—and avant-garde, using a non-canonical material to interrogate consumer culture. His works sell not just as images but as surfaces, their textures impossible to ignore.

Untitled (Chadwick), in particular, has been read as emblematic of his ability to fuse art history with social commentary. The Chadwick reference grounds it in lineage; the cigarettes and cash place it in lived reality; the plasticine medium bridges them with irony.

Viewers often oscillate between fascination and discomfort. The work is visually lush, its textures seductive. Yet its subject matter is grim: addiction, excess, detritus. The seduction and repulsion operate simultaneously, forcing reflection.

A Still Life for the Anthropocene

Henry Hudson’s Untitled (Chadwick) is more than a depiction of a tabletop. It is a microcosm of contemporary existence: the mingling of art and commerce, consumption and waste, history and banality. Through the stubborn, synthetic tactility of plasticine, Hudson monumentalizes the ephemeral, insisting that our detritus deserves attention because it defines us.

Where traditional still lifes reminded viewers of the brevity of life, Hudson’s work reminds us of the longevity of our waste. In the Anthropocene, it is not fruit that rots but plastic that persists. Cigarettes will burn out, but plasticine will remain, a fossil of modern life.

By invoking Chadwick, Hudson situates himself in a lineage of sculptural inquiry, yet he does so with irony, humor, and critique. His is not the permanence of steel but the persistence of petroleum. Untitled (Chadwick) thus stands as a vanitas for our time—a reminder that what we consume and discard is, in the end, the true portrait of who we are.

No comments yet.