when tradition becomes architecture

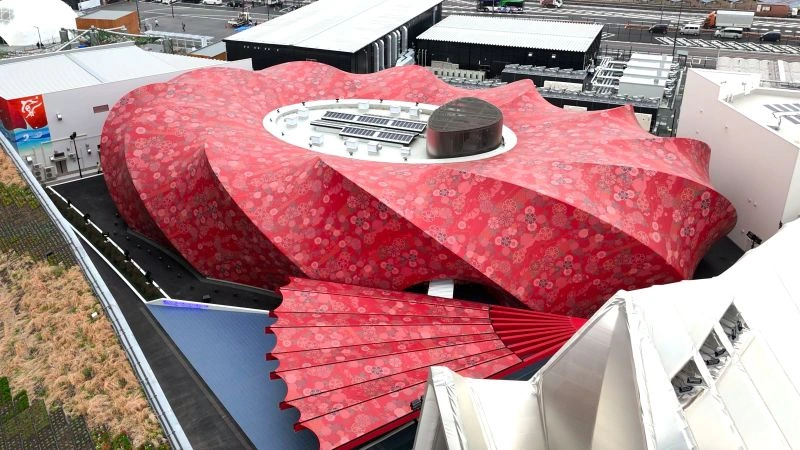

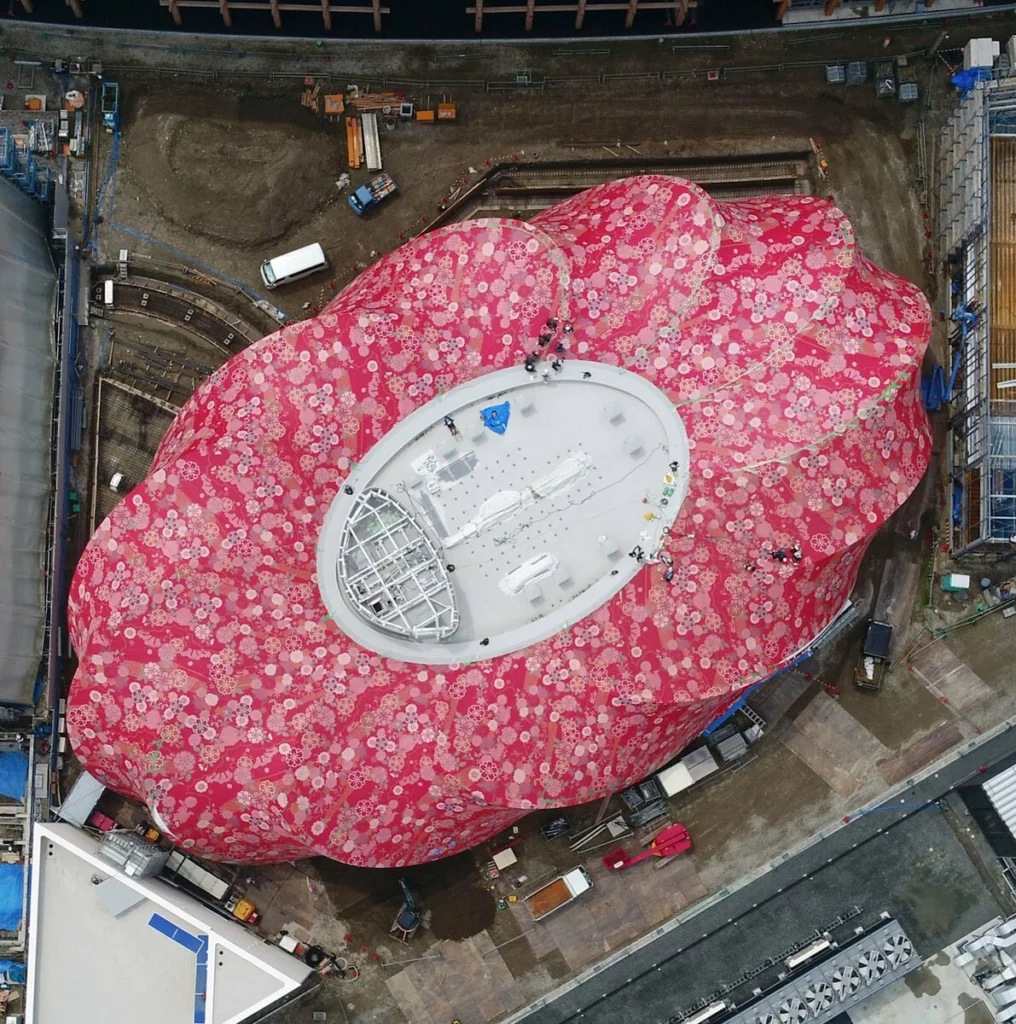

At this year’s Expo in Osaka, one pavilion rises above the rest—not in height, but in texture. Amid the sinuous forms of rope-based installations, rattan canopies, and pneumatic membranes, a single structure stands out: a bold red building cloaked in shimmering floral fabric. This isn’t paint, nor plastic, nor projection—it’s Nishijin brocade, the centuries-old silk textile from Kyoto. The building, wrapped entirely in the intricate weave, covers over 30,000 square feet of surface area and has earned the Guinness World Record for the largest building ever enveloped in Jacquard fabric.

Behind this monumental gesture stands Hosoo, the 300-year-old Kyoto weaving house that has transformed a craft born in the Imperial Court into a symbol of contemporary Japanese innovation. For the Expo, Hosoo didn’t simply decorate a pavilion; it redefined what fabric could mean at architectural scale—how a material associated with kimonos, ceremonies, and intimate haute could now clothe an entire building.

weave

To understand Hosoo’s accomplishment in Osaka, one must begin in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, where the art of silk weaving has flourished for over twelve centuries. In the Heian period, master artisans developed techniques to supply brocades and fine silks to the Imperial Court and aristocracy. Each thread carried not just pigment, but hierarchy—each pattern, a code of social distinction.

Hosoo was founded in 1688, deep within this tradition. For centuries, it specialized in the production of obi and furisode—the elaborately woven sashes and long-sleeved kimonos used for formal occasions. But unlike many heritage houses that became relics of nostalgia, Hosoo refused stasis. As Japan industrialized, as Western aesthetics arrived, as fashion globalized, the brand continued to weave—literally and metaphorically—toward new forms of expression.

When Masataka Hosoo, the twelfth-generation head of the family, took the reins in 2020, he inherited not merely a company but a question: how to keep a 300-year-old tradition relevant in the digital century. His answer lay not in mass production but in precision artistry—a continuation of his ancestors’ pursuit of beauty “without regard for cost or efficiency.”

View this post on Instagram

flow

Today, visitors to Hosoo’s flagship store in Kyoto’s Karasuma Oike neighborhood find a brand that bridges eras. The exterior—a stark, black monolith surrounded by rammed earth walls—reveals little. But inside, the space gleams with silk cushions, curtains, and garments that shimmer under ambient light, their textures oscillating between metallic and ethereal.

The second-floor gallery feels like a meditation on material. Textile panels, some over a yard wide, hang like paintings—fields of subtle gradients, luminous threads, or pixelated monochrome geometries that evoke digital code. They feel closer to visual art than fabric, yet they stem from the same looms that once produced ceremonial obi.

In an appointment-only showroom upstairs, the brand’s traditional offerings still hold court: handcrafted kimono fabrics woven with gold thread and dyed with painstaking precision. But as Hosoo’s team emphasizes, this duality—the coexistence of past and present—is not contradiction but continuity. Each fabric, either destined for a temple, a couture gown, or a gallery wall, arises from the same principle: beauty as an end in itself.

the art of inefficiency

Masataka Hosoo describes his philosophy with almost monastic clarity. “We are based on a tradition of weaving pursued without regard for cost or production efficiency,” he says. “It comes from a background of order-made woven textiles of the highest quality. Beauty was the only objective.”

This approach may seem counterintuitive in a world driven by automation and scalability. Yet, for Hosoo, inefficiency is not a defect but a declaration. It asserts the value of time, skill, and imperfection—the human touch embedded in every thread. Each brocade demands a choreography of artisanship: designing patterns, preparing the loom, aligning metallic threads, and weaving silk filaments at sub-millimeter precision.

The result is a fabric that carries a depth impossible to replicate by machine—a visual rhythm born from the slight tension variations, the shimmer that shifts under light, the resonance of hand and heritage.

tech

What sets Hosoo apart is its embrace of technology not as replacement, but as reverence. The company collaborates with Kyoto’s Institute of Advanced Technology and global design studios to translate digital data into woven form. Using Jacquard looms connected to computer systems, Hosoo’s artisans can render digital imagery in thread—transforming pixels into pattern while preserving the tactile richness of silk.

This synthesis of tradition and innovation has opened unions with global architects, designers, and brands—from Louis Vuitton and Chanel to Tesla and Rolls-Royce. Each partnership expands Nishijin’s relevance, embedding Kyoto’s textile DNA into objects of modern desire.

At the Osaka Expo, this convergence reached its zenith. The massive red pavilion wrapped in Hosoo brocade was not just a spectacle—it was a data-driven tapestry, its design informed by algorithms that manipulated color gradients and motifs drawn from traditional Japanese flora. The weave itself became a dialogue between hand and machine, past and present, intimacy and scale.

fabric as architecture

The Osaka installation pushes the very boundaries of what textile can be. To wrap an entire structure—30,000 square feet—in silk brocade required reengineering the material’s structural behavior. The fabric, traditionally used for garments and interiors, had to withstand wind, humidity, and UV exposure without losing its luster.

Hosoo’s engineers developed a hybrid system that combined natural silk with synthetic reinforcement fibers, coated for weather resistance. The result is a textile that maintains the tactile delicacy of Nishijin but functions like an architectural skin—breathable, resilient, luminous.

Walking around the pavilion, the visual effect is mesmerizing. In daylight, the red fabric ripples like a living organism, its gold threads catching the sun in rhythmic pulses. At night, LED lighting behind the textile transforms it into a glowing lantern, a beacon of Japanese artistry rendered in contemporary form.

In this moment, Nishijin brocade transcends its traditional domestic context. It no longer drapes bodies or interiors—it dresses architecture, elevating fabric from ornament to structure.

philosophy

For Hosoo, innovation is not rupture but evolution. The company’s philosophy rests on what Masataka calls “cultural continuity through transformation.” This means respecting the past not by replicating it, but by extending it into the future.

In Kyoto, this ethos manifests in the brand’s multi-disciplinary collaborations. Hosoo works with artists and researchers to explore how textile design can influence sound, light, and even scent. The firm has developed acoustic panels using woven silk to enhance spatial resonance and is experimenting with luminous threads woven with fiber optics.

Each of these projects continues a line of thought that began over a millennium ago: how material can convey meaning. For the court weavers of old, brocade expressed hierarchy and ceremony; for Hosoo today, it expresses human ingenuity and cultural resilience.

style

The Expo pavilion also embodies a deeper conversation about sustainability. In an era dominated by fast fashion and synthetic production, Hosoo’s slow, intentional approach feels almost radical. By prioritizing craftsmanship and longevity, the brand advocates for a return to the rhythm of nature and tradition.

Silk, unlike synthetic textiles, is biodegradable and renewable. Hosoo’s process involves natural dyes and local sourcing, minimizing environmental impact while maximizing cultural value. The Osaka pavilion’s afterlife has also been carefully planned: once the Expo concludes, the fabric panels will be reconfigured into artworks, garments, and educational materials—ensuring that the story of the brocade continues beyond its architectural debut.

culture

Earning a Guinness World Record for the largest building wrapped in Jacquard fabric is more than a technical milestone; it’s a cultural statement. It positions Japan’s ancient weaving tradition alongside cutting-edge architecture and design, proving that heritage can still astonish on the world stage.

Visitors to the Expo are drawn not only by the structure’s visual magnetism but by its emotional resonance. It’s a reminder that progress need not erase the past; rather, the past can be the foundation for innovation. Hosoo’s work invites us to see textile not as mere material but as narrative—a living document woven across centuries.

The pavilion’s floral motifs, rendered in red and gold, symbolize vitality and prosperity—colors deeply embedded in Japanese cultural identity. At a time when global attention is fixed on technology, Hosoo’s creation redirects the gaze to human craft as a form of technology in itself: the original interface between mind and material.

organization

Back in Kyoto, Hosoo’s headquarters continues to serve as both workshop and cultural embassy. The brand’s collaborations now extend to the global art world: exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Cooper Hewitt in New York, and design fairs in Milan and Paris.

Yet Hosoo remains deeply rooted in Kyoto’s community. The company trains young artisans, preserving weaving techniques that might otherwise vanish. It also supports cross-disciplinary residencies, inviting digital artists, architects, and musicians to reinterpret Nishijin’s visual language.

Through these efforts, Hosoo is not simply exporting Japanese heritage—it is evolving it, ensuring that the concept of beauty as purpose remains relevant in a data-driven world.

impression

The Hosoo pavilion at the Osaka Expo is more than an architectural marvel. It’s a manifesto written in thread—a testament to how cultural heritage can evolve without losing its soul. In its shimmering red surface, centuries of Kyoto craftsmanship meet the ambitions of a new Japan: one that balances artistry with innovation, memory with movement.

By wrapping a building in Nishijin brocade, Hosoo has done more than set a record; it has set a precedent. The gesture redefines what it means for a nation to present itself to the world—not through spectacle alone, but through the quiet strength of its craft traditions.

From the imperial courts of Kyoto to the global arena of Expo Osaka, Hosoo’s story is the story of Japan itself: a culture that transforms continuity into creativity, weaving its past into the very fabric of the future.

No comments yet.