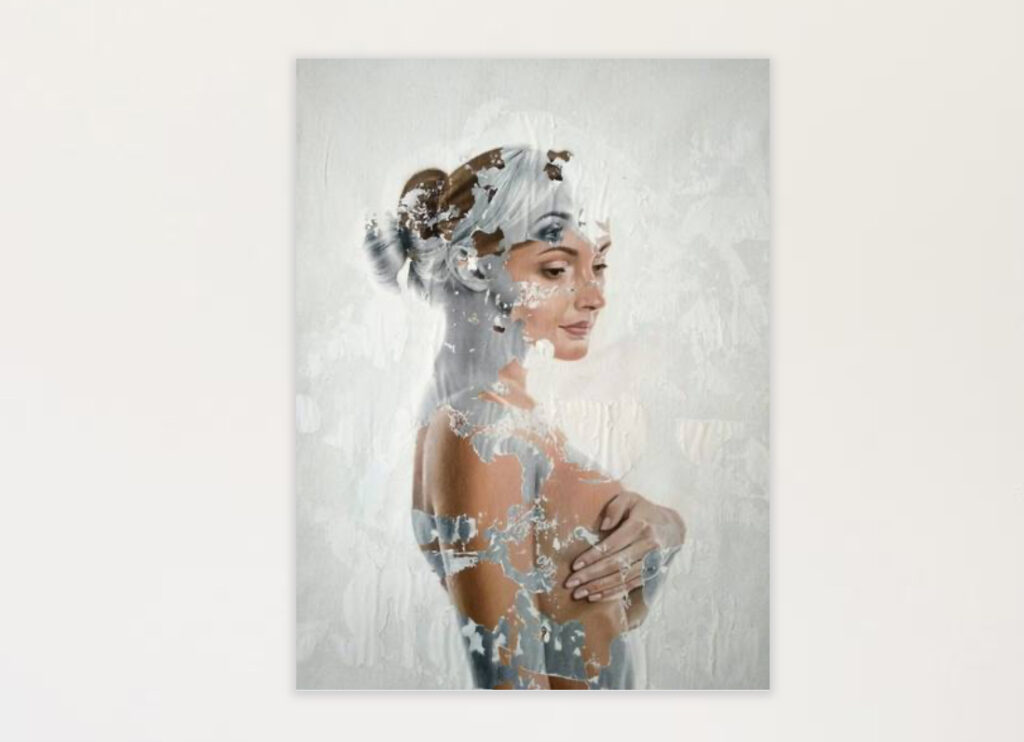

In Intus a me, Spanish artist Raúl Lara offers more than a portrait. He constructs a psychological mirror, a metaphysical proposition rendered through acrylic paint. At first glance, the painting presents a serene female figure, painted with hyperreal precision, her pose inward, almost meditative. But the surface is deceptive. Through deliberate textural erosion and veils of white, Lara breaks down the illusion of wholeness, creating a layered image of internal fragility and quiet resistance. The result is not merely a woman’s likeness; it is a distilled encounter with the act of self-witnessing.

A Dual Grammar of Realism and Abstraction

Lara’s command of hyperrealism is evident in the detailed rendering of the subject’s face and upper body. Her gaze, turned sideways, is neither confrontational nor evasive—it’s contemplative. Her skin is warm, human, real. The folds of her fingers, the contour of her arm, the subtle bend of her shoulder—they read like tender memories preserved in flesh.

But then the abstraction ruptures that reality.

Overlaying this precise realism is a veil of texture—cracked paint, intentional scarring, what looks like peeling plaster or dried, brushed whitewash. The layering technique recalls the decay of old frescoes, or walls once rich in life now blanched by time. The effect destabilizes the viewer’s perception: Are we looking at a portrait hidden behind weathered glass? Or a self erased by its own internal motion?

Lara’s technique isn’t decorative—it’s symbolic. The decaying white overlay evokes the layered processes of memory, repression, and identity. It’s a visual language of erosion. In some places, the overlay almost obliterates the figure; in others, it peels back just enough to reveal her clearly, as if the self were being uncovered through time—or perhaps buried under it.

The Latin of the Soul: “Intus a me”

The title, Intus a me, is Latin. Translated loosely, it means “within myself.” It sets the tone of introspection, of an internal landscape made visible. This is not a portrait in the conventional sense—it’s not a depiction of appearance. It’s a manifestation of inwardness. In that light, the peeling paint becomes psychological. It’s the visual metaphor of what lies beneath: layers of self-perception, trauma, nostalgia, doubt, pride.

This painting dares to externalize the inner self, not through expressive color or gesture, but through methodical erasure.

What makes the image unsettling is its quietness. There is no dramatic pose, no overt emotional display. The figure appears calm, but her calm is the eye of a storm that has passed—or is yet to come. The tension between the serenity of the subject and the chaos of the surrounding surface is central to Lara’s achievement. It’s not melodrama he courts—it’s subtle existential fracture.

Feminine Presence and Vulnerability

The subject, a woman, stands with arms folded gently across her chest. The pose suggests self-protection, modesty, introspection. But it is not weakness—it’s containment. A form of strength expressed in inwardness. The artist does not objectify her; instead, he venerates her as a symbol of psychological depth and embodied memory.

Through the abrasions in the surface, her body becomes terrain—fragmented, exposed, raw. This is a statement on vulnerability, but not victimhood. Lara refrains from idealizing or dramatizing the female figure. Rather, he gives her autonomy. Her interiority becomes the true subject.

By breaking the conventional visual “skin” of the painting, Lara draws attention to the inner workings of identity. What are we made of? What memories, wounds, and hopes are layered beneath the version of ourselves we present to the world? In Intus a me, the feminine form becomes a vessel for this inquiry—not as an object of the gaze, but as the agent of its own excavation.

Material as Message

Lara’s use of acrylic is important. Acrylic, with its quick-drying properties and its potential for both precision and layering, allows him to oscillate between control and accident. The white, scraped textures appear to have been applied and then distressed—partly intentional, partly subject to chance. This push and pull between order and entropy parallels the human psyche: composed, but unstable; present, but shifting.

The tactile nature of the medium calls attention to surface—while paradoxically pointing beyond it. The painting becomes sculptural in its textures. It invites not just looking but a kind of mental touch. You feel the urge to reach out, to trace the cracks, to peel back the white veil and see more of her. And that’s precisely the point. The work evokes that longing—to truly know, to truly see—while reminding us that total access to the self is impossible.

Between Silence and Statement

One of the most compelling aspects of Intus a me is its silence. There is no background narrative, no symbolic props, no noise. Just a woman, fragmented and whole at once. In this silence lies its strength.

But silence is not the absence of speech. It is a kind of utterance in itself. Lara’s painting speaks through quiet: through gesture, surface, texture. It evokes not a story, but a condition—what it means to live with the self, to examine the self, to remain with oneself long enough to see not just the polished version, but the ruptures too.

In this sense, the painting functions as an existential mirror for the viewer. We do not simply look at her—we see ourselves looking at her. Her self-regard prompts ours. The longer we observe, the more we’re implicated. It becomes not just her portrait, but a reflection of our own interior weathering.

Contemporary Context

In an era where art often favors spectacle, speed, or ideological assertion, Raúl Lara’s Intus stands apart. It resists the urge to shout. It whispers. But in that whisper is a profound ethical stance: a return to slowness, to depth, to ambiguity.

Lara’s work belongs to a tradition of artists—Lucian Freud, Jenny Saville, Gerhard Richter—who blur the boundaries between realism and abstraction to uncover truth rather than depict it. But unlike these artists, Lara doesn’t focus on distortion or excess. His disruptions are subtle, almost quiet. And in that restraint, he achieves something rare: a sense of timelessness.

This painting could belong to no particular year. It is not dated by politics, fashion, or even digital aesthetics. It exists in a psychological and aesthetic space that feels universal. That makes it haunting. And enduring.

Impression

Intus a me is not a puzzle to solve; it is a meditation to inhabit. It asks us to sit with complexity. To recognize that within each of us lies a self we may never fully know. That memory, identity, and time are not linear, but layered—scratched, painted over, eroded, revealed again.

Raúl Lara has painted not a woman, but an experience. The experience of being human, being layered, being unfinished. He gives us not a subject, but a space: a space to ask, What lies within me? What remains unspoken, untouched, unpeeled? And more importantly: What do I choose to reveal—and what do I let fade into the white?

No comments yet.