Few names in modern science and conservation carry the resonance of Jane Goodall. Known globally for her pioneering research on chimpanzees in Tanzania, Goodall has transformed the way we see not only our closest living relatives but also ourselves. Her work is not just a collection of discoveries—it is a testament to patience, empathy, and vision.

Goodall’s story is more than scientific history; it is a lesson in perseverance and the power of curiosity. Beginning her work at the age of 26, she entered a field that at the time was dominated by men and constrained by rigid scientific conventions. By daring to observe chimpanzees on their own terms, she brought the world insights that would forever change the way we understand animal behavior, human evolution, and the urgency of conservation.

From Bournemouth to Gombe

Born in Bournemouth, England, in 1934, Goodall displayed an early fascination with animals. From studying earthworms to spending hours in a henhouse, she demonstrated an unusual ability to focus on observation and detail—traits that would later define her scientific career. Stories of her youthful curiosity—such as disappearing for hours to watch how a chicken laid an egg—reveal the budding field researcher who would one day astonish the world.

Her dream, nurtured through books like Tarzan of the Apes and Doctor Dolittle, was simple yet radical: to live among animals in Africa. Without a university degree or formal training, she seemed an unlikely candidate. Yet a chance meeting with Louis Leakey, the renowned paleoanthropologist, opened the door to her destiny. Recognizing her passion and patience, Leakey sent her to Tanzania in 1960 to begin a study of chimpanzees at Gombe Stream National Park.

A New Approach to Science

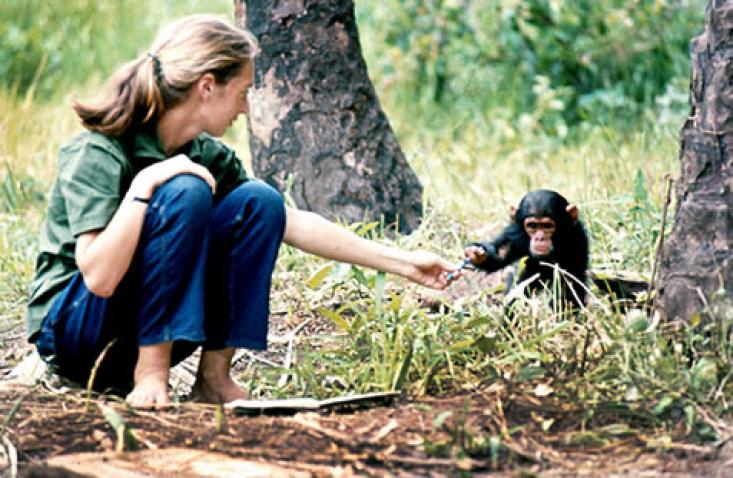

Goodall’s arrival at Gombe marked a turning point in the study of animal behavior. Rather than applying detached observation from a distance, she immersed herself fully in the environment of the chimpanzees.

Her methodology was unconventional. Instead of assigning numbers to her subjects, she gave them names: David Greybeard, Flo, Goliath, and others. At the time, the scientific establishment dismissed such practices as unprofessional, fearing anthropomorphism. But Goodall insisted that individuality, personality, and emotion were not human exclusives—they were visible in chimpanzees as well.

Her persistence paid off. After months of patient observation, the chimps began to accept her presence, allowing her to witness behaviors no one had documented before.

Landmark Discoveries

The most famous of Goodall’s discoveries came when she saw David Greybeard stripping the leaves from a twig to fish termites from their mound. This observation shattered the prevailing belief that tool use was the hallmark of humanity. Louis Leakey, upon hearing the news, remarked: “Now we must redefine tool, redefine man, or accept chimpanzees as human.”

Social Dynamics and Warfare

Goodall’s long-term observation revealed complex social structures within chimpanzee communities. She documented alliances, dominance struggles, and even instances of coordinated violence, such as the “Four-Year War” between factions at Gombe. These behaviors highlighted both the darker and more cooperative sides of primate society.

Emotional Lives

Equally transformative were her insights into the emotional depth of chimpanzees. She described mothers tenderly nurturing infants, adolescents playing with abandon, and entire communities showing grief at the death of a group member. Her insistence that animals feel joy, fear, and sorrow broadened the scope of animal behavior studies and blurred long-held lines between humans and other species.

Beyond Research: A Global Voice for Conservation

Goodall’s influence did not end with her fieldwork. By the 1980s, she shifted much of her energy toward advocacy, recognizing that the survival of chimpanzees depended not only on scientific understanding but also on global action.

She founded the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977, dedicated to research, conservation, and community engagement. Through initiatives like Roots & Shoots, launched in 1991, she empowered young people around the world to take direct action for the environment, animals, and humanity. Her message was one of hope and responsibility: every person has the power to make a difference.

The Power of Storytelling

One of Goodall’s greatest gifts has been her ability to communicate science as a story accessible to all. Books such as In the Shadow of Man, Through a Window, and Reason for Hope blend rigorous observation with personal reflection. She does not merely present data; she invites readers into the forests of Gombe, introducing them to the personalities of its inhabitants and the ethical challenges of conservation.

Her lectures and public appearances, often delivered with gentle conviction, have reached audiences ranging from schoolchildren to heads of state. She has demonstrated that science and empathy are not mutually exclusive but mutually reinforcing.

Redefining Conservation

A cornerstone of Goodall’s advocacy is her recognition that conservation cannot succeed without addressing the needs of local communities. She argued that protecting chimpanzees and their habitats required empowering the people who lived alongside them.

This approach—linking conservation with sustainable development—was ahead of its time. Today, it is considered best practice. By fostering education, alternative livelihoods, and healthcare initiatives, the Jane Goodall Institute has created models where human well-being and wildlife protection are not opposing forces but complementary goals.

Influence on Women in Science

Goodall also stands as a trailblazer for women in a field historically dominated by men. Her success opened doors for female primatologists such as Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas, collectively known as Leakey’s “Trimates.” She demonstrated that scientific breakthroughs do not depend on conforming to rigid stereotypes but on curiosity, determination, and fresh perspectives.

Her courage in defying convention—whether by naming animals, acknowledging their emotions, or entering the male-dominated world of field science—continues to inspire women and underrepresented groups across disciplines.

Criticism and Vindication

Over the years, Goodall faced criticism for anthropomorphism and for her deeply empathetic approach. Critics argued that her style blurred the line between science and sentiment. Yet, time has largely vindicated her. Modern science increasingly acknowledges animal sentience, individuality, and emotional complexity—principles that Goodall championed decades earlier.

Her holistic vision of science—one that embraces empathy alongside data—has become not only validated but celebrated.

Flow

Goodall’s story transcends academia. She has been the subject of documentaries, including the acclaimed Jane (2017), which used rediscovered archival footage of her early years at Gombe. She has been depicted in literature, art, and popular culture, symbolizing the harmony possible between humanity and nature.

Her image—gentle yet resolute, with binoculars in hand among the forests of Gombe—has become an emblem of both scientific discovery and moral stewardship.

Impression

Jane Goodall’s life’s work has redefined the boundaries between human and nonhuman, science and empathy, research and advocacy. By daring to watch, to wait, and to care, she revealed that the differences between us and chimpanzees are not as vast as once thought. More importantly, she reminded humanity of its responsibility to protect the natural world that sustains all life.

Her journey from a young dreamer in England to one of the most respected figures in science and conservation underscores a profound truth: that curiosity, patience, and compassion can reshape not only a field of study but also the conscience of the world.

Goodall has not only shown us chimpanzees; she has shown us ourselves. And in that reflection lies both a challenge and a promise: to honor the connections she unveiled and to act with the responsibility those connections demand.

No comments yet.