lang

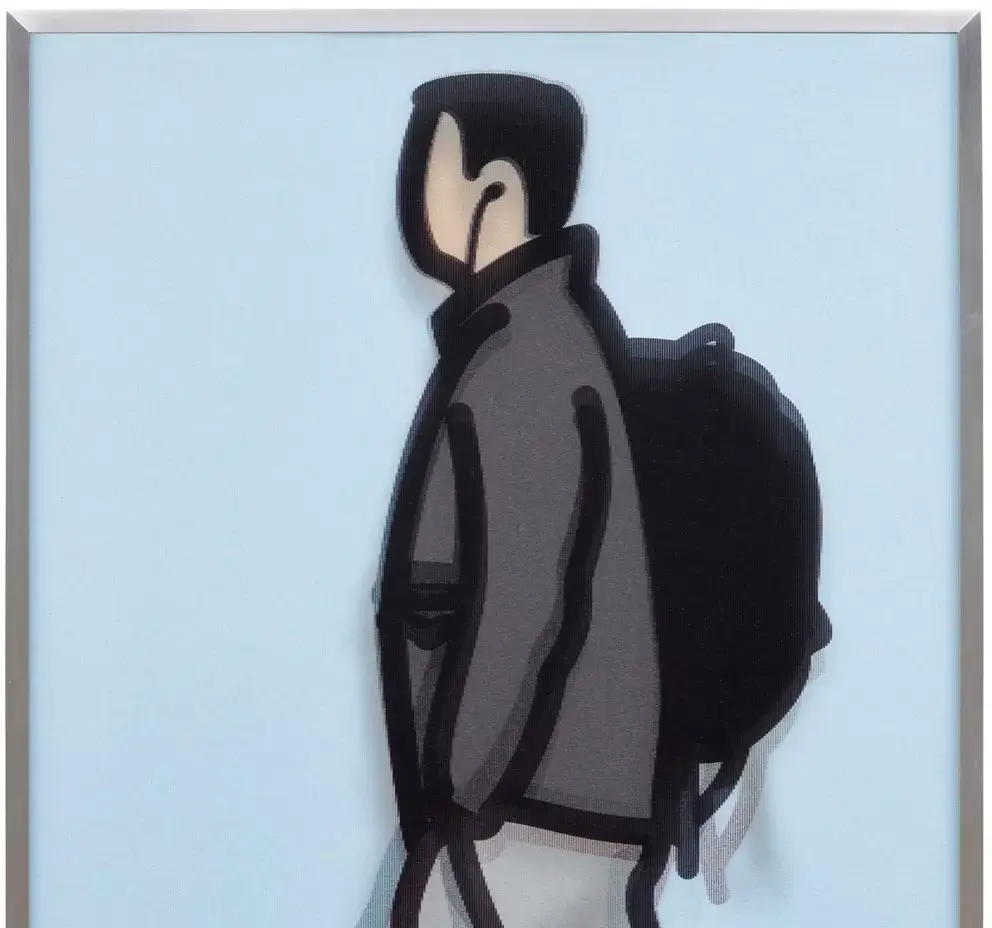

Julian Opie’s Student, from Walking in London 1 (2013) exists in a space between stillness and motion, between portraiture and signage, between the individual and the anonymous mass of the city. At first glance, the work appears characteristically simple: a stylized figure, flattened into clean lines and blocks of colour, caught mid-stride. But this apparent simplicity is deceptive. The work operates through a sophisticated visual system that collapses time, movement, and identity into a single, continuously shifting surface.

The lenticular format is central to this effect. As the viewer moves past the panel, the figure animates—legs advancing, arms swinging, the body walking forward. Motion is not depicted; it is activated. The artwork only completes itself through the viewer’s movement, creating a quiet reciprocity between image and observer. In Opie’s world, seeing is never static.

opie

Opie’s practice has long been defined by reduction—not as minimalism in the strict sense, but as a deliberate stripping away of excess information. Facial features are removed, expressions flattened, bodies rendered as silhouettes or outlined forms. This reduction does not erase individuality; instead, it shifts identity from psychological depth to structural presence.

In Student, the figure is recognizable not by face but by posture, clothing, and gait. The backpack, casual attire, and youthful stance situate the subject socially and culturally without naming them. The title reinforces this anonymity. “Student” is not a name but a role, a category, a position within the urban ecosystem. The figure stands in for countless others, becoming both specific and universal.

Opie’s visual language draws from multiple sources: traffic signage, digital avatars, Japanese woodblock prints, and the logic of early computer graphics. Yet his work resists nostalgia. The flatness of his figures does not reference a past aesthetic so much as it mirrors the visual economy of contemporary life—icons, interfaces, symbols designed for rapid recognition rather than contemplation.

style

The use of a lenticular acrylic panel transforms Student from an image into an event. Lenticular printing, often associated with novelty or advertising, allows multiple images to occupy the same physical surface, revealing themselves sequentially as the viewing angle changes. In Opie’s hands, this technique becomes a tool for embedding time into a static object.

The four inkjet prints that comprise Student represent successive moments in a walking cycle. Unlike traditional animation, there is no beginning or end. The motion loops endlessly, refusing narrative progression. The student walks perpetually, going nowhere and everywhere at once.

This perpetual motion echoes the rhythms of the city itself. Urban life is defined less by destinations than by flows—commuters, pedestrians, crowds in transit. Opie does not depict the city directly in this work, but its presence is implicit. The blank background allows the figure to be placed mentally anywhere: a street, a campus, a crossing, a pavement in London or any other global city.

sys

The series title, Walking in London 1, anchors the work geographically, yet London is not depicted through landmarks or architecture. Instead, it is implied through behavior. Walking becomes the defining gesture of urban citizenship. To walk is to participate in the city’s tempo, to move within its systems without necessarily commanding attention.

Opie’s London is not cinematic or monumental. It is procedural. People move through it, not toward spectacle but through routine. The student’s anonymity reflects the city’s scale, where individuality coexists with constant anonymity.

This approach aligns with Opie’s broader interest in how cities are experienced rather than how they are seen. His work often avoids panoramic views or descriptive detail, focusing instead on the human figure as a unit of motion within a larger, unseen structure.

show

Traditional portraiture aims to capture likeness, character, or inner life. Opie rejects this premise entirely. In Student, there is no facial expression, no eye contact, no emotional cue. Yet the work is undeniably a portrait.

What Opie offers instead is a portrait of function. The student is defined by what they do—walk—rather than who they are internally. This shift reflects a contemporary condition in which identity is often read through roles, behaviors, and external markers rather than introspection.

The absence of facial detail does not flatten meaning; it redistributes it. The viewer is invited to project themselves or others into the figure. The student could be anyone. The work’s emotional resonance emerges not from empathy with a specific individual, but from recognition of a shared condition.

clear

The colour palette in Student is restrained and deliberate. Opie avoids expressive or symbolic colour in favor of clarity and legibility. The colours define form, separate limbs, and reinforce motion, but they do not narrate mood.

This neutrality is key to the work’s openness. By resisting expressive colour, Opie prevents the figure from being emotionally coded. The student is not melancholic, joyful, hurried, or relaxed. They simply walk. The work remains observational rather than interpretive.

The clean separation of colour fields also reinforces the graphic quality of the figure, aligning it with signage and interface design. The student becomes readable at a distance, instantly legible in the way contemporary visual culture demands.

move

In Opie’s practice, movement often functions as a substitute for expression. Gait becomes character. The way a body moves through space communicates social identity, age, and context more effectively than facial detail.

In Student, the walking cycle is casual and unforced. There is no urgency, no tension. This relaxed movement suggests youth, routine, and familiarity with the environment. The student belongs here. They are not lost, rushed, or out of place.

This subtlety is important. Opie does not dramatize urban life. He records it. The student’s walk is unremarkable—and that is precisely the point. The work elevates the ordinary without aestheticizing it.

view

Because the lenticular effect requires physical movement to activate, the viewer becomes part of the work’s logic. To see the student walk, the viewer must walk as well—side to side, adjusting their position. This embodied viewing experience mirrors the subject matter, creating a quiet loop between observer and observed.

The artwork thus resists passive consumption. It cannot be fully apprehended from a single vantage point. It demands time, movement, and attention, even as it depicts an everyday, almost unnoticed action.

This reciprocity reinforces Opie’s interest in how images function in public space. His works often exist outside traditional gallery contexts—on billboards, screens, and architectural surfaces—where viewers encounter them while moving. Student retains this public logic even within an institutional frame.

idea

As part of a larger series, Student gains additional resonance. Opie’s repeated depiction of walking figures—men, women, professionals, passersby—builds an archive of urban movement. Each figure is distinct yet interchangeable, reinforcing the idea of the city as a system composed of countless similar gestures.

Seriality in Opie’s work does not produce monotony; it produces structure. By repeating the act of walking across different figures, he constructs a visual vocabulary of contemporary life. Student is one unit within this vocabulary, contributing to a broader portrait of urban existence.

rel

In an era dominated by screens, avatars, and flattened representations of the self, Opie’s work feels increasingly prescient. The simplified human figure has become a standard mode of representation across digital platforms. Yet Opie’s figures retain a physicality that digital icons often lack. They move, they occupy space, they require bodily engagement to be fully perceived.

Student sits at the intersection of digital aesthetics and material presence. The inkjet prints, acrylic surface, and Dibond mounting assert the object’s physicality even as the imagery echoes screen-based visuals. This tension between material and immaterial mirrors contemporary life itself.

fin

Student, from Walking in London 1 is not a dramatic work. It does not shock, provoke, or overwhelm. Its strength lies in its quiet persistence. The student walks endlessly, without destination, without interruption.

In doing so, Opie captures something fundamental about modern life: the constant, unremarkable movement that defines our days. The work does not ask us to stop and stare; it asks us to notice what we usually overlook.

Through reduction, repetition, and motion, Julian Opie transforms walking into a visual language—one that speaks not of individual psychology, but of collective experience. Student becomes less a portrait of a person than a portrait of a condition: moving through the city, one step at a time.

No comments yet.