Rediscovering a Quiet Visionary

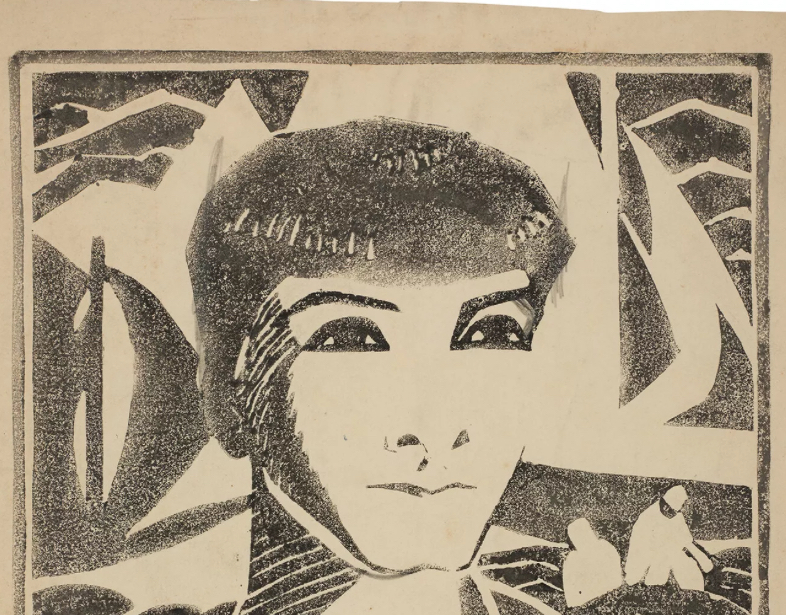

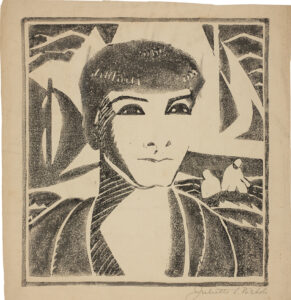

Though not widely recognized in mainstream art history narratives, Juliette Nichols stands as a quietly compelling figure among early 20th-century printmakers. Her woodcut [Portrait with Sails and Two Fishermen], dated circa 1915, captures the convergence of human character, maritime life, and expressionist technique. In two versions—both printed in black ink, one with delicate hand-additions in graphite—the work offers more than surface observation. It invites the viewer into a study of rural labor, solitude, and coastal atmosphere, filtered through a strikingly modern eye.

Rendered on laid paper and retaining wide margins, the piece reflects a moment when artists were turning to printmaking not just for reproduction, but as a medium of experimentation and expression. The simplicity of woodcut, with its reliance on line, shadow, and texture, becomes in Nichols’ hands a tool of emotional depth. This essay delves into the work’s composition, technical execution, historical background, and broader cultural context.

The Woodcut Medium in Context

To appreciate Nichols’ achievement, it’s crucial to understand the revival of woodcut printmaking during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1915, artists in Europe and North America had turned to the woodcut for its boldness, economy, and expressive potential—drawing inspiration from Japanese ukiyo-e prints, German Expressionism, and Arts and Crafts sensibilities.

Unlike etching or lithography, woodcut printing requires artists to carve directly into a block of wood, removing areas they do not wish to print. This process demands decisive mark-making, rewarding bold compositions and rhythmic contrast. While often seen as a more primitive or “folk” art form, many modernists embraced woodcut as a democratic, tactile response to industrialization.

Nichols’ choice of woodcut links her to this broader movement of artists seeking authenticity and directness in their materials.

Visual Composition: Narrative in Layers

At the heart of [Portrait with Sails and Two Fishermen] is a complex tension between individual presence and environmental space. The title hints at multiple layers: a portrait, maritime symbols, and working figures—each operating visually and symbolically.

In the foreground, we likely encounter the “portrait” itself: perhaps a solitary figure, rendered with heavy outlines and firm shadows, their expression obscured but evocative. This character—possibly a woman or a weatherworn man—anchors the composition with contemplative weight.

Behind or around this figure emerge two fishermen, suggested with simplified outlines—one seated, one standing. Their placement isn’t purely literal. It creates a triangular visual rhythm and suggests a timeless bond between human toil and nature.

In the upper register or flanking space, sails rise—abstracted yet recognizable—perhaps moored ships or idle rigs. The sails provide verticality and balance against the horizontal figures, contributing to the print’s overall geometry.

Together, these elements reflect a life defined by the sea—its labor, isolation, and interdependence. Nichols doesn’t offer a dramatic scene. Instead, she presents a layered stillness: a quiet narrative embedded in form.

Technical Execution: Ink, Graphite, and Deliberate Minimalism

The existence of two prints—both woodcuts in black ink, one with additional graphite detailing—shows Nichols’ interest in the dialogue between mechanical reproduction and personal intervention.

In the primary version, the use of black ink alone allows the raw qualities of the block to dominate. We see strong linework, areas of cross-hatching, and possibly broken textures suggesting sand, wind, or woodgrain.

The second version, with hand-applied graphite, reveals Nichols’ more intimate engagement with the print. Graphite may have been used to soften facial features, emphasize shadows, or create tonal variation—bridging the gap between print and drawing. This hybrid approach places Nichols in conversation with contemporaries who resisted the purely mechanical aesthetic of mass printing.

Laid paper, with its visible chain lines and subtle texture, provides both a historical authenticity and a tactile dimension to the work. Paper choice matters in printmaking: here it supports the rustic tone of the subject matter and adds depth to the inky forms.

Themes and Symbolism

Though specific identities are absent, the characters in [Portrait with Sails and Two Fishermen] suggest broader archetypes:

- The solitary figure may represent reflection, resilience, or the inner life of a coastal inhabitant.

- The fishermen evoke labor, tradition, and male camaraderie.

- The sails suggest commerce, departure, waiting—the inescapable movement of life dictated by tide and time.

In 1915, Europe was immersed in the trauma of World War I, and though Nichols’ scene is not overtly political, it resonates with a world losing its stability. The sea, long a source of sustenance and freedom, had also become a theater of war. There’s a mournful stillness in the print—a quiet observation of a lifestyle under threat or already receding.

Juliette Nichols in Art Historical Perspective

Little biographical information survives about Juliette Nichols, but her work—especially if part of a larger corpus—speaks volumes. She appears aligned with a number of trends:

- Regionalism and social realism: capturing local life with honesty and restraint.

- Expressionist tendencies: bold carving, emotional undercurrents.

- Modernist simplification: stripping form to its essentials.

While many women artists of the time struggled for visibility, Nichols’ work, with its refined technique and psychological weight, deserves a place alongside contemporaries like Gwen Raverat, Frances Gearhart, and Edna Boies Hopkins, all of whom brought sensitivity and strength to printmaking in the early 20th century.

Her approach stands apart from urban modernism; it favors rural narratives, perhaps placing her within an American or British coastal context. If more of her work survives, it could enrich our understanding of female printmakers working outside mainstream avant-garde centers.

Collectibility and Legacy

As interest grows in early 20th-century printmakers, works like Nichols’ are receiving renewed attention from collectors, scholars, and curators. The dual versions of this woodcut are especially valuable—not only as artworks but as documents of process and intention.

For collectors, Nichols’ hand-enhanced edition offers a unique insight into her decision-making. For museums, the work bridges gaps between genres: portraiture, marine art, and modernist abstraction.

Its restrained aesthetic also aligns well with today’s renewed taste for minimalist and handcrafted art, especially works that speak to sustainability, labor, and human presence.

The Enduring Quiet Power of Nichols’ Vision

Portrait with Sails and Two Fishermen by Juliette Nichols may be over a century old, but it feels startlingly fresh. Through economical linework, thoughtful composition, and subtle enhancements, Nichols captured not only a moment in maritime life, but something essential about human endurance and interconnectedness.

At a time when the world was unraveling in war and industry, she turned her eye to the quiet rituals of ordinary life. In doing so, she created a timeless image—grounded in place, rich in texture, and layered with meaning.

In rediscovering Nichols, we don’t just recover a forgotten printmaker—we reconnect with a tradition of art that values observation over spectacle, labor over haute, and depth over drama.

No comments yet.