design as a wink

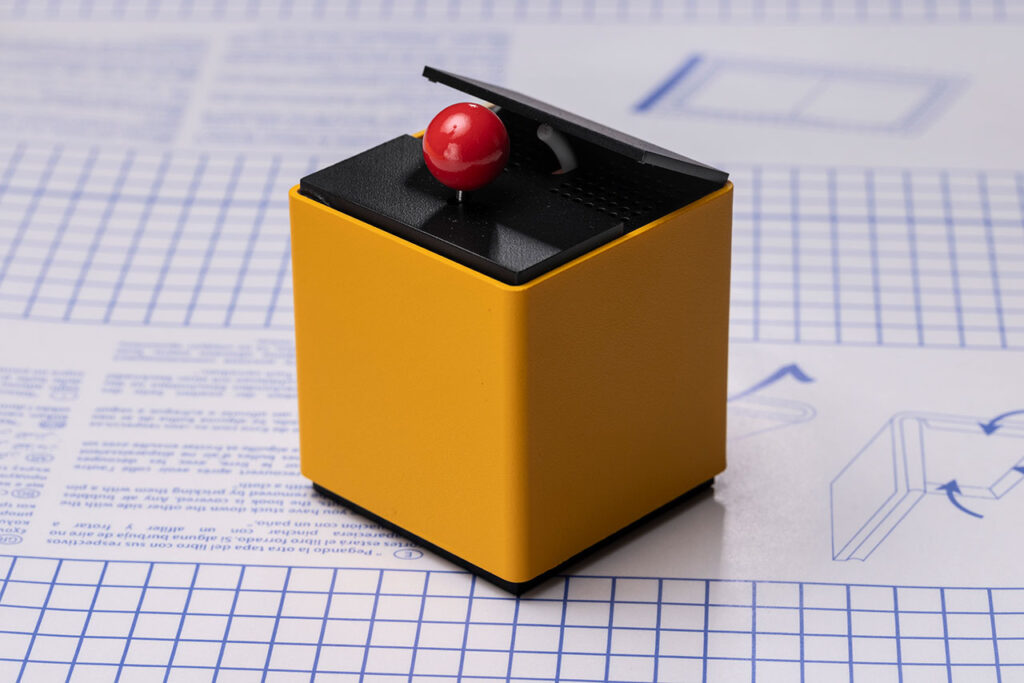

In an era of hyper-smart devices, it takes a rare kind of wit to build an object that does absolutely nothing. That’s exactly what French “internet of things” engineer Olivier Mével and Elium Studio have done with La Machine—a vividly geometric device that re-examines the legendary “useless machine” first conceived by Marvin Minsky in the mid-20th century.

Minsky’s contraption was famously absurd: flip a switch, and a mechanical arm emerges solely to flip it back off. It was a paradox made physical—a machine designed to defeat itself. Mével’s La Machine inherits that same philosophical humor but re-imagines it for an era when devices listen, predict, and monetize our every action. In a world where technology constantly insists on utility, La Machine stands proudly defiant—its purpose is to have none.

La Machine operates exactly like Marvin Minsky’s original “useless machine.”

-

You flip a switch on the top.

-

After a short delay, a small hinged arm inside the box activates, slowly rising through an opening.

-

The arm’s only purpose? To flip the switch back off — and then retreat into the box, closing the lid behind it.

That’s it.

No lights, no connectivity, no hidden function. The motion is clean, rhythmic, and strangely satisfying — a little theater of mechanical futility.

the useless lineage

The “useless machine” began as a thought experiment in cybernetics, a provocation about automation and autonomy. Later popularized by science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke and engineer Claude Shannon, it became an icon of mid-century curiosity—a minimalist sculpture of logic and futility.

Mével, whose past work often bridged connected devices and poetic absurdity (from connected weather sensors to speculative IoT prototypes), treats Minsky’s invention less as nostalgia than as cultural critique. “We live surrounded by smart things,” he once told a Paris design panel, “so making something perfectly dumb feels like an act of resistance.”

memphis logic and color rebellion

To give the object visual punch, Mével enlisted Elium Studio, the Parisian design collective known for its clear-eyed minimalism. Yet here, minimalism takes a vacation. Instead, La Machine erupts in color, pattern, and play—a deliberate nod to Ettore Sottsass and the Memphis Milano movement he founded in 1981.

Sottsass rejected the austerity of modernism, embracing plastics, zig-zags, and pop surrealism. His furniture pieces—think the Carlton room divider or Tahiti lamp—turned serious design into exuberant theater. In La Machine, that spirit lives again: vibrant laminate surfaces, offset geometries, and an unapologetic sense of humor animate what could easily have been a sterile gadget.

The color palette recalls Sottsass’s hallmark contrasts—cerulean against vermilion, lemon yellow set against deep onyx—while the form itself toys with modular architecture. The switch protrudes like a miniature totem; the lid opens with almost theatrical deliberation to reveal the inner arm, which instantly slams it shut again.

Every interaction is both comic and choreographed, a reminder that design can perform as much as function.

philosophy through conjure

What makes La Machine so compelling is how it merges interaction design and art philosophy. It critiques the promise of “smart living” through performative absurdity. The user presses a button expecting response or reward, only to be rebuffed. In that moment, La Machine exposes the dependency loop of modern interfaces: how we’ve been trained to seek feedback, confirmation, data.

It’s a philosophical joke disguised as a toy, one that echoes thinkers like Jean Baudrillard, who once suggested that contemporary objects seduce us through simulation rather than function. Mével’s box doesn’t pretend to be helpful; it refuses to be instrumentalized. By doing so, it returns agency to the observer—it makes us laugh, then think.

a conversation piece for the algorithmic century

At first glance, La Machine might look like an eccentric collectible for design enthusiasts, but its cultural resonance runs deeper. The object stands as a commentary on automation fatigue: our fridges reorder groceries, our phones guess our emotions, our watches track our sleep—and still, satisfaction remains elusive.

By celebrating mechanical redundancy, Mével reminds us that imperfection and purposelessness can be human virtues. The device’s repetitive motion even feels therapeutic—like a metronome reminding us that rest, too, has rhythm.

Collectors who’ve previewed the first prototypes compare it to an art edition by Alessi or a kinetic sculpture by Daniel Rozin—an industrial-design object that flirts with absurd performance art.

craft

Despite its conceptual humor, La Machine is built with genuine care. The casing is CNC-cut from high-density wood composite, wrapped in printed laminate reminiscent of Memphis furniture, and assembled by hand in Paris. The inner mechanism is 3D-printed and servo-driven, controlled by a micro-board coded with a single line of defiance: “turn off.”

The engineering irony is delicious—an Internet-of-Things specialist builds a fully autonomous object, yet it’s permanently offline. No app, no data, no firmware. Its only loop is physical and existential.

echoes of sottsass

Sottsass often said he designed not furniture but “furniture for conversations.” La Machine operates on the same principle. Place it on a desk or shelf, and it immediately invites questions. Children laugh, engineers lean closer, philosophers nod knowingly.

Like Memphis design, it rejects neutrality. Its colors refuse to blend into domestic calm; its gesture—quick, decisive—breaks the quiet. In a time when most electronics hide behind soft-touch greys and seamless UX, Mével’s box stands proud, declaring its presence through playful aggression.

In this way, La Machine becomes a meta-object: a design artifact about design itself. It challenges the lineage from Bauhaus purity to Silicon Valley invisibility, reasserting emotion and irony as legitimate tools of creation.

reception

Since its reveal, La Machine has circulated across European design circles, appearing in Paris galleries and viral social posts alike. The reactions range from admiration to amusement, but almost always—reflection. One critic for Designboom FR called it “the anti-Alexa.” Another compared it to “a postmodern Tamagotchi that refuses care.”

Limited editions are rumored to be forthcoming—possibly in numbered colorways or collaborative runs with design schools. Yet Mével insists that production scale isn’t the point. “It’s an idea machine,” he says, “not a product.”

impression

In 2025, when every device competes to be indispensable, La Machine redefines luxury as disconnection. It’s a witty reminder that usefulness is overrated, and that sometimes, the highest form of intelligence is refusal.

Through humor, craftsmanship, and a dash of Memphis rebellion, Olivier Mével and Elium Studio have given the world something genuinely rare: a machine that brings us back to ourselves.

Flip the switch, watch it flip back—and remember that not every interaction needs a purpose to have meaning.

No comments yet.