British illustration has a long, complex, and often overlooked history—one rendered not in oil or bronze, but in ink and observation. The Global Street Art organization’s collection, titled Largely Forgotten Artists, does more than rescue artworks from the margins of memory; it offers a layered view into Britain’s evolving social psyche, revealing how illustration served not just as decoration or entertainment, but as a mirror—sometimes cracked, sometimes gleaming—of the nation itself.

Spanning over 150 years, this remarkable archive presents original works by illustrators who chronicled war, politics, humor, and the sharp edge of social change. Many of these artists worked in near anonymity, despite shaping how generations understood the world around them. Today, in a visual culture saturated with memes, logos, and algorithmic branding, the raw clarity and intentionality of these works feel urgent—like unearthed whispers from a more honest time.

The Role of Illustration: Art, Commentary, Memory

Before photography dominated reportage and digital tools replaced ink, illustrators were society’s sharpest observers. They rendered scenes from memory, sketching public moods and private contradictions. From satirical cartoons to technical renderings, illustration offered immediacy with meaning—a hybrid of aesthetics and interpretation.

The Global Street Art collection, by naming its archive Largely Forgotten Artists, makes a poignant argument: many of these figures, once seen widely in magazines and books, have been excluded from the mainstream narrative of art history. Their works, however, remain strikingly modern in tone and relevance, not only for what they show but for how they show it. A hand-drawn satire of a political scandal, a wartime sketch with minimal linework but maximum emotion, or a whimsical take on industrial advancement—these are not mere cultural artifacts, but active participants in their eras.

Drawing Society: Then and Now

One of the more fascinating elements of the Largely Forgotten Artists collection is how it captures the shifts in both subject and style over the decades. Early British illustration—like that of the 19th century—leaned on realism, with compositions heavy in detail and moral symbolism. These works reflected the rigid structures of Victorian Britain, where art had to be legible in its values and loyal in its construction.

As Britain entered the 20th century—buffeted by the forces of two world wars, decolonization, and industrial upheaval—its illustration evolved. Political cartoons, often published in Punch or The Illustrated London News, became platforms for critique rather than celebration. The human form was caricatured; buildings were abstracted; social ills were made visible through wit and exaggeration.

This shift is stylistically obvious too: what begins as elegant, detailed draftsmanship in the 1800s slowly loosens into more expressive, cartoony work in the postwar years. While some might interpret this evolution as a loss of skill, it’s more accurately a reflection of changing priorities. Realism gave way to suggestion. Precision gave way to symbolism. The essence of a moment began to matter more than its surface appearance.

Thematic Threads: Politics, War, Humor, Technology

Global Street Art’s collection is organized thematically as much as chronologically. These themes—politics, war, humor, and technology—are not just subjects; they are entry points into British history itself.

Politics, unsurprisingly, dominates much of the early 20th-century work. Newspapers and magazines relied heavily on illustrators to comment on elections, foreign affairs, and royal scandals. Caricatures of prime ministers, monarchs, and foreign leaders were not only allowed—they were eagerly consumed by the public. It was a time when illustration could influence public opinion more swiftly than any printed speech.

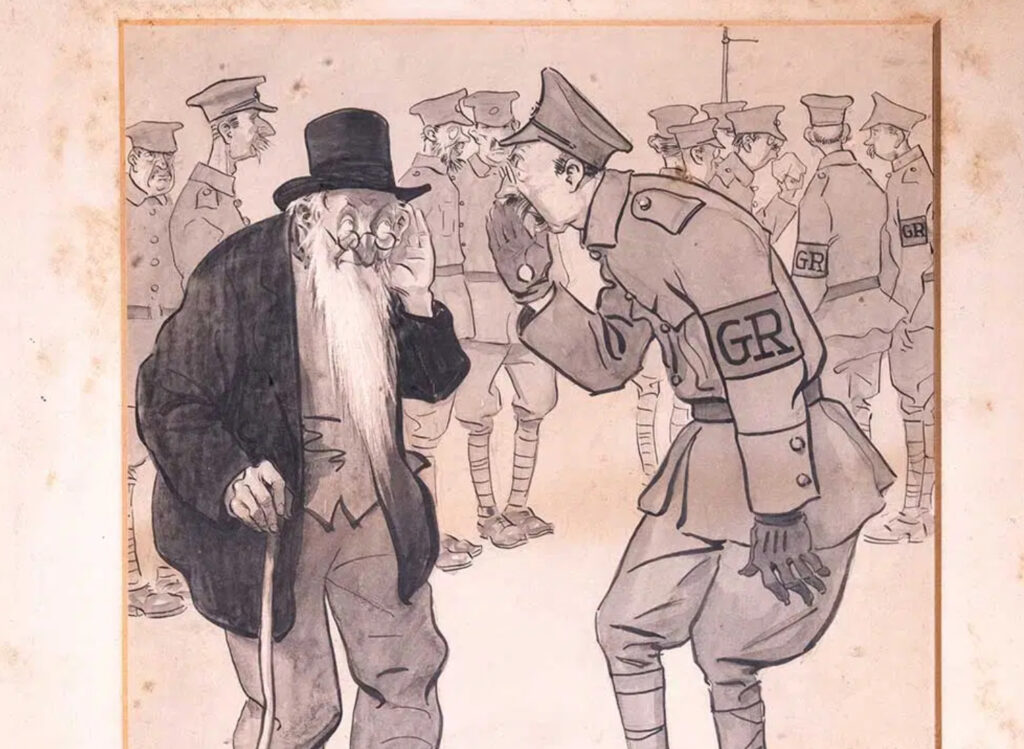

War—especially the First and Second World Wars—elicited an entirely different register. The illustrations from this era carry both gravitas and sarcasm. Ernest Howard Shepard, for example, famously contributed political cartoons to Punch, often addressing the absurdity of military bureaucracy or the resilience of the British spirit. One poignant piece from the collection shows soldiers lined up not by name, but by number, humorously underscoring the dehumanizing efficiency of war.

Humor is perhaps the most universally resonant theme. British illustration has long possessed a sharp, dry wit that cuts through class structures and institutional authority. Even in the grimmest times, cartoonists found ways to laugh—often at themselves. This comic sensibility is one of the throughlines of the archive, proof that illustration served not just to document but to console and disrupt.

Technology enters the frame as both fascination and anxiety. As trains, factories, and eventually computers crept into everyday life, illustrators responded with skepticism and wonder. Some works from the mid-century period depict robotic figures taking over human tasks, decades before automation became a real concern. Others romanticize the machinery itself, framing it as a new kind of sublime.

Ernest Howard Shepard and the Legacy of Linework

Though widely remembered today for his illustrations in A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh books, Ernest Howard Shepard was equally accomplished in political cartooning. His dual talent reflects the fascinating duality of many illustrators of the time—they were not siloed into “children’s art” or “serious work.” Instead, their skill moved fluidly between the fantastic and the factual.

One of Shepard’s cartoons in the Largely Forgotten Artists collection critiques military bureaucracy with elegant irony: soldiers are assigned numbers that strip them of individuality, a subtle but powerful comment on the mechanization of humanity. His linework is delicate yet firm, composed but deeply emotional. That Shepard’s work could span from whimsical woodland creatures to biting wartime satire speaks to the versatility required of illustrators in that era. They were not just artists—they were cultural translators.

Why They Were Forgotten—and Why They Shouldn’t Be

The question lingers: why were these artists forgotten? Partly, it’s because illustration was long considered subordinate to fine art. While painters and sculptors were celebrated in galleries and textbooks, illustrators were often dismissed as craftspeople or commercial laborers.

Moreover, the rise of photography and digital media altered the function of visual commentary. In an age of instant images and viral graphics, the hand-drawn line began to seem quaint. Editorial budgets shifted. Illustration was either replaced by photos or rendered so sleek and commercial that it lost its tactile appeal.

But forgetting these illustrators is a cultural loss. Their work not only reflects the emotional topography of Britain but also expands our understanding of what constitutes meaningful art. These were not abstract expressionists or conceptual provocateurs—they were observers, record-keepers, and critics. They made sense of the world in pen and paper, often under deadline, often without acclaim.

Illustration Today: Echoes and Relevance

Ironically, in the contemporary art world, the aesthetics and techniques of historical British illustration are making a return—often via street art, indie publishing, and zines. Artists working today cite these early works as key influences, from their humor to their social edge. The Largely Forgotten Artists collection now becomes more than just an archive—it becomes a sourcebook for today’s visual resistance.

Remembering With Purpose

To remember these illustrators is not merely to dust off the past—it’s to reconnect with a form of expression that remains potent and relevant. The Largely Forgotten Artists collection invites us to look closely at the margins of British art history, and in doing so, reshapes the center.

These artists did not paint to be enshrined in white cubes or to headline retrospectives. They illustrated because the world demanded it. Their pens recorded laughter, fear, resistance, and absurdity.

We live in a world increasingly driven by visuals. In such a world, remembering the illustrators who first showed us how to see becomes more than nostalgic—it becomes necessary.

No comments yet.